The President’s Message:

Our April 9th,

speaker will be Dr. Robert Watson.

He is a professor of America History at Lynn University.

I look forward to his presentation.

If anyone has a

program that they would like to present, please speak to me at the

meeting or call me.

I was pleased that

Patrick Falci was able to be our speaker in March.

Many of his presentations are on YouTube (Do a Google search for

Patrick Falci).

Gerridine LaRovere

March

12, 2025 Program:

Patrick

Falci was our March speaker and as usual he brought Joe Wheeler to life

with drama, exuberance, historical accuracy.

Joseph "Fighting Joe" Wheeler was born on September 10, 1836.

Although of New England ancestry and directly descended from the

English Puritans who came to New England, he was born near Augusta,

Georgia. However, he considered himself a son of the South. Patrick

Falci was our March speaker and as usual he brought Joe Wheeler to life

with drama, exuberance, historical accuracy.

Joseph "Fighting Joe" Wheeler was born on September 10, 1836.

Although of New England ancestry and directly descended from the

English Puritans who came to New England, he was born near Augusta,

Georgia. However, he considered himself a son of the South.

He was a soldier who wore many uniforms. The first

of these was the gray cloth of a cadet at the United States Military

Academy at West Point.

Wheeler entered West Point in July 1854, barely meeting the height

requirement. He was only 5' 2" at the time of entry.

He graduated on July 1, 1859, placing 19th out of 22

cadets, and was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 1st

U.S. Dragoons. Donning a

blue uniform on June 26, 1860, he reported to the Regiment of Mounted

Rifles stationed in the New Mexico Territory.

He fought in a skirmish with Indians and picked up the nickname

"Fighting Joe."

From the years 1861 to 1865 he wore Confederate

grey fighting the Union blue.

In April 1862, first lieutenant served at Shiloh in the 19th Alabama under

Braxton Bragg. During the

Siege of Corinth in April and May, Wheeler's men while on picket duty

repeatedly clashed with U.S. patrols.

Serving as acting brigade commander, Wheeler burned the bridges

over the Tuscumbia River to cover the Confederate retreat to Tupelo, MS.

During the war it looked like “Fighting Joe” was everywhere.

He was in the West, in the deep south, and in the East, and

fought using the style of mounted cavalry known as “cut, slash, and

run.”

first lieutenant served at Shiloh in the 19th Alabama under

Braxton Bragg. During the

Siege of Corinth in April and May, Wheeler's men while on picket duty

repeatedly clashed with U.S. patrols.

Serving as acting brigade commander, Wheeler burned the bridges

over the Tuscumbia River to cover the Confederate retreat to Tupelo, MS.

During the war it looked like “Fighting Joe” was everywhere.

He was in the West, in the deep south, and in the East, and

fought using the style of mounted cavalry known as “cut, slash, and

run.”

His Civil War career came to an end while

attempting to cover Confederate President Jefferson Davis's flight south

and west in May 1865.

Wheeler was captured at Conyers' Station just east of Atlanta.

Wheeler was imprisoned for two

months, first at Fort Monroe and then in solitary confinement at Fort

Delaware, where he was paroled on June 8, 1865.

After the War Wheeler settled near Courtland,

Alabama. His home, Pond

Spring, is in an area now known as Wheeler, Alabama.

Joe was not in good health and was bothered by a nervous

condition. His doctor suggested he “get married to calm him down.”

Wheeler took that advice. He married Daniella Jones Sherrod and

they had six children. He

tried farming, small business, and the law before entering into

politics.

In 1880, Wheeler was elected to the U.S. House of

Representatives in a hotly contested race. He served most of the term

only to have the results of the election overturned.

His opponent, Col. William M. Lowe, a fiery leader of the

Independent Democrats, took over the seat but died soon after.

Wheeler returned to Congress in 1885 to replace Lowe and served

there until 1900.

In 1898, Wheeler, at age 61, volunteered for the

Spanish–American War.

Fighting Joe had become a crusader for pushing the United States toward

war with Spain. He received

an appointment as major general of volunteers from President William

McKinley. From that

beginning he earned a regular army commission as a brigadier general.

Some former U.S. and Confederate officers noted the irony of

Wheeler serving in the U.S. Army.

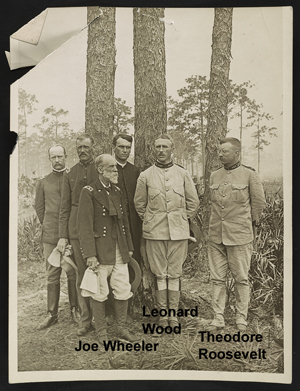

The story

becomes entwined with the life of Theodore Roosevelt.

Like Joe, Teddy wanted to go to war.

The administration liked the idea that a senior Confederate

officer was rejoining the Army in service for the country.

Wheeler assumed command of the cavalry division, which included

Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders.

This division was under the command of General William R.

Shafter, Fifth Army Corps.

Roosevelt had formed the Rough Riders himself and recognized that he

lacked army experience. He enlisted Leonard Wood to command the unit.

TR assumed the rank of lieutenant colonel under Wood.

Rounding out the famous names was First Lieutenant John “Black

Jack” Pershing. He got the

title “Black Jack” because he was a white officer leading a unit of

Buffalo Soldiers, the black calvary fighters in the post-Civil War army.

The cavalry units were formed in Texas, then

shipped to Tampa, FL and transported to Cuba. However, logistics were a

nightmare. The army needed

to get to Cuba fast, but the troops were green. Supplies took a long

time to get to Florida, and ocean transportation was limited.

The Americans planned to destroy Spain's army forces in Cuba and

capture the port city of Santiago de Cuba.

To reach Santiago they had to

pass through concentrated Spanish defenses in the San Juan Hills.

The limits on transport ships meant that, except for a few

officers, the cavalry had no horses.

The Rough Riders fought on foot.

Once the fighting started, old Joe Wheeler seemed

to have forgotten which war he was fighting.

During the excitement of the battle, Wheeler called out, "Let's

go, boys! We've got the damn

Yankees on the run again!"

If this really happened, he would have been promptly reminded that he

was one of the “damned Yankees.”

During the excitement of the battle, Wheeler called out, "Let's

go, boys! We've got the damn

Yankees on the run again!"

If this really happened, he would have been promptly reminded that he

was one of the “damned Yankees.”

Wheeler fell seriously ill during the campaign and

turned over command of the division to Brig. Gen. Samuel S. Sumner.

In July, Wheeler was still incapacitated.

When the Battle of San Juan Hill began, he heard the sound of

guns. Once again, the "War Child" returned to the front despite his

illness. He was the senior

officer at the front. Upon

taking the heights, Wheeler assured General William R. Shafter that the

position could be held against a counterattack.

He led the division through the Siege of Santiago and was a

senior member of the peace commission.

When back in the United States, Wheeler commanded the

convalescent camp of the army at Montauk Point.

Wheeler sailed for the Philippines to fight in the

Philippine–American War, arriving in August 1899.

He commanded the First Brigade in Arthur MacArthur's Second

Division until January 1900.

During this period, Wheeler was mustered out of the volunteer service

and commissioned a brigadier general in the regular army. He reentered

the organization he had resigned from over 39 years before.

After hostilities, he commanded the Department of the Lakes until

his retirement on September 10, 1900, and moved to New York City.

He retired

at the age of 64, but continued to travel to be of aid to U.S. Army

veterans. After a prolonged

illness, Wheeler died in Brooklyn on January 25, 1906, at the age of 69.

He is one of the few Confederate officers buried within Arlington

National Cemetery.

Last changed: 04/02/25 |