The President’s Message:

I am so pleased that Patrick Falci, actor and historian, will be

presenting his program on Wednesday, March 12, 2025 at the Lake Clarke

Shores Town Hall. Patrick

always has an interesting and informative presentation.

The subject will be

Fighting Joe Wheeler – Once a General Always a General.

Guests are welcomed. I will

be serving a pound cake that I will bake from a Civil War recipe.

Come One; Come All.

I look forward to seeing you at the March meeting.

Gerridine La Rovere

February 12, 2025

Program:

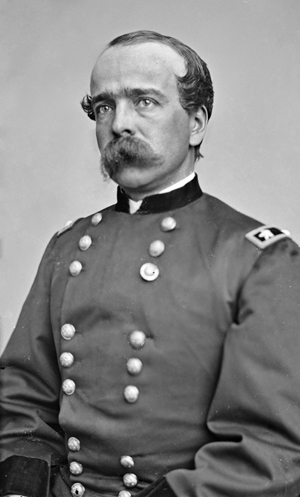

Daniel Adams Butterfield (1831 – 1901)

Who was the general whose name is associated with Taps?

Daniel Adams Butterfield was born in Utica, New York, on October

31, 1831. He was the third

son (of nine children) born to John Butterfield and Melinda Baker

Butterfield. John

Butterfield was a prominent Utica businessman who pioneered the transportation business.

He was instrumental in starting America's first overland express

service. He was a stage

coach driver as a young man.

Butterfield had smart business acumen.

As president of Overland Stage Company, he won a contract from

the U.S. government in 1858 to carry mail between St. Louis and San

Francisco in three weeks.

This was a remarkable feat in the era before the transcontinental

railroad. He was the

founding member of Butterfield, Wesson, and Company and was one of the

first to make profits by the rapid movement of merchandise. This company

would become the American Express Company.

He was also a director of the Utica City National Bank.

John was instrumental in building a telegraph line between

Buffalo and New York.

who pioneered the transportation business.

He was instrumental in starting America's first overland express

service. He was a stage

coach driver as a young man.

Butterfield had smart business acumen.

As president of Overland Stage Company, he won a contract from

the U.S. government in 1858 to carry mail between St. Louis and San

Francisco in three weeks.

This was a remarkable feat in the era before the transcontinental

railroad. He was the

founding member of Butterfield, Wesson, and Company and was one of the

first to make profits by the rapid movement of merchandise. This company

would become the American Express Company.

He was also a director of the Utica City National Bank.

John was instrumental in building a telegraph line between

Buffalo and New York.

Young Daniel Butterfield was enrolled in Utica Academy, a private

school. In 1849,

Butterfield was involved with an arson fire in Utica which caused the

death of a citizen. He was

indicted in 1851 for the crime based on a statement by a co-conspirator

who was subsequently hanged.

But Daniel had the charges dropped in 1853.

He graduated from Union College in Schenectady, New York in 1849.

It was unusual to graduate at such an early age, 18.

He then took up the study of law.

At Union College he had a fair record and was known as a leader

and somewhat of a prankster.

After beginning his preliminary study of law, Butterfield found

himself too young to enter the bar, so he decided to embark on an

extended trip to the west.

He began in the Territory of Minnesota.

He journeyed through the forests with an Indian guide.

He boarded a steamer to New Orleans where he had the opportunity

to study the influence of slavery on the population as well as the

political climate of the South. He stated later that it was there that

his feelings towards slavery were born.

When he returned to Utica, he joined the Utica Citizens' Corps, a

local militia organization.

Working for his father, he was entrusted with preparing a timetable and

a schedule for the Overland Stage line running between Memphis, St.

Louis, and San Francisco.

Butterfield moved to New York City shortly afterwards and became the

eastern superintendent of the American Express Company.

He joined the 12th regiment of the New York State militia and

despite his lack of military experience, rose quickly to the rank of

colonel. When the Civil War

began, the 12th Regiment mustard in New York City on April 19, 1861 and

sailed for Washington, DC.

After arriving, the unit was assigned guard and garrison duty in the

capital.

On

May 24, Butterfield's regiment was at the head of the Union column that

advanced into Alexandria, Virginia.

The 12th served in the Shenandoah Valley during the Bull Run

campaign. While serving as

a colonel of the 12th, Butterfield received word from American Express

on August 15, 1861, that he would continue drawing his full salary as

superintendent of the company for the duration of the war.

Butterfield was soon promoted to brigadier general and given

command of the Third Brigade of the Fifth Army Corps, Army of the

Potomac, which included the 83rd Pennsylvania Volunteers.

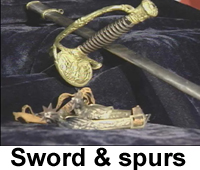

In May 1862 Butterfield led his men at the Battle of Hanover

Court House, after which he was presented with a set of gold spurs from

admiring officers. The

spurs are engraved. "To

General Daniel Butterfield.

Presented by field officers of the Third Light Brigade, Porters [sic]

Division, Army of the Potomac.

For our admiration of your brilliant generalship on the field of

Hanover Court House May 27, 1862."

The spurs were presented to him by Colonel Strong Vincent of the

83rd Pennsylvania. On

May 24, Butterfield's regiment was at the head of the Union column that

advanced into Alexandria, Virginia.

The 12th served in the Shenandoah Valley during the Bull Run

campaign. While serving as

a colonel of the 12th, Butterfield received word from American Express

on August 15, 1861, that he would continue drawing his full salary as

superintendent of the company for the duration of the war.

Butterfield was soon promoted to brigadier general and given

command of the Third Brigade of the Fifth Army Corps, Army of the

Potomac, which included the 83rd Pennsylvania Volunteers.

In May 1862 Butterfield led his men at the Battle of Hanover

Court House, after which he was presented with a set of gold spurs from

admiring officers. The

spurs are engraved. "To

General Daniel Butterfield.

Presented by field officers of the Third Light Brigade, Porters [sic]

Division, Army of the Potomac.

For our admiration of your brilliant generalship on the field of

Hanover Court House May 27, 1862."

The spurs were presented to him by Colonel Strong Vincent of the

83rd Pennsylvania.

In the spring of 1862, Butterfield prepared and printed a manual on camp

and outpost duty for infantry. Published by Harper Brothers, New York

City, this exhaustive book includes standing orders, extracts from the

revised regulations for the Army, rules for health, maxims for soldiers,

and duties of officers.

Butterfield's unit took part in a battle at Gaines Mill near Richmond,

Virginia. On June 27, 1862,

despite a serious injury, Butterfield seized the colors of the 83rd

Pennsylvania and rallied the regiment to hold their ground during a

critical time in the battle.

This action allowed the army of the Potomac to withdraw safely to

nearby Harrison's landing.

He later received the Medal of Honor for that act of heroism.

It was during this time that his association with the bugle call Taps

started. Butterfield was no

stranger to bugle calls. He

knew their importance and had composed a special unit or prelude call.

He had trained his buglers, in the use of the unit call; among

those was the young bugler of the 83rd Pennsylvania Oliver Wilcox

Norton. Daniel Butterfield

is credited with composing Taps and the special prelude call for that

brigade which is mentioned in the scene from the movie

Gettysburg

which depicts the one thing that young lieutenant gets wrong in singing

one too many of Butterfield.

Outside of that the description is accurate.

He also goes on to describe Taps as "Butterfield's lullaby."

At

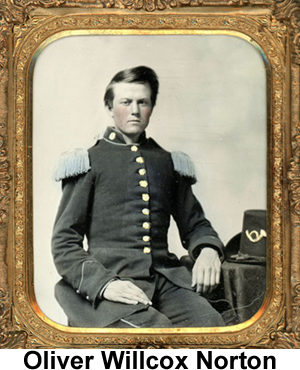

this point we will now discuss Oliver Wilcox Norton.

He was a modest, self-effacing Pennsylvania schoolteacher, who

left behind one of America's lasting military legacies.

His civil War service, including the perils of combat, the joys

of perfecting a classic bugle, and leading men of color into battle.

Norton's post war writings contributed greatly to our

understanding of the struggle for Little Round Top at the Battle of

Gettysburg in July 1863.

Moreover, he helped compose "Taps," the timeless bugle call honoring

fallen soldiers. Lastly,

the free-thinking Norton served as an officer for two years in the 8th

U.S. Colored Infantry. At

this point we will now discuss Oliver Wilcox Norton.

He was a modest, self-effacing Pennsylvania schoolteacher, who

left behind one of America's lasting military legacies.

His civil War service, including the perils of combat, the joys

of perfecting a classic bugle, and leading men of color into battle.

Norton's post war writings contributed greatly to our

understanding of the struggle for Little Round Top at the Battle of

Gettysburg in July 1863.

Moreover, he helped compose "Taps," the timeless bugle call honoring

fallen soldiers. Lastly,

the free-thinking Norton served as an officer for two years in the 8th

U.S. Colored Infantry.

Born in 1839 in Allegheny County, NY, Norton was one of 13 children in a

Presbyterian minister's family.

At age 20, he taught school and farmed near Gerard in

northwestern Pennsylvania.

When the war erupted, he was already a member of the local militia

called Gerard's Guards, which later became a company of Col. John

McLane's "Erie Regiment."

The regimen's three-month term expired without any military action.

Norton, then a private, followed his colonel into the newly

formed 83rd Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers, and became the bugler

of Company K.

The 83rd suffered casualties at Gaines' Mill, one in a series of

engagements that comprise the Seven Days Battle outside of Richmond in

June and July, 1862.

Wounded there, Norton survived and returned to duty in time to

participate in the Battle of Melvern Hill on July 1.

As the regiment recuperated at Harrison's Landing along the James

River following the fight, Norton joined Gen. Daniel Butterfield's staff

as its bugler. While

encamped at Harrison's Landing, he and Butterfield perfected an old

French army bugle call into present-day Taps.

That tattoo was used for "lights-out."

Butterfield later wrote of the endeavor, "the call of Taps did not seem

to be as smooth, melodious, and musical as it should be... and then...

Norton got it to my taste without (me) being able to write music or

knowing the technical name of any note, but, simply by ear."

Neither Norton nor Butterfield fully appreciated what they had

achieved. Norton became the

first bugler to sound the new Taps, probably at "Lights-out" sometime in

mid-July 1862. Taps spread

throughout the Army of the Potomac, and soon found its way to other

Union armies, and even some Confederate forces.

Not before long, Taps also sounded over the graves of deceased

soldiers memorializing their service as a truly magnificent eulogy.

The Taps authors remained anonymous for more than 35 years until, by

happenstance, Norton and Butterfield revealed their roles in creating

the tune to the public in response to an 1898 article in Century

Magazine. In May 1863,

Colonel Strong Vincent assumed command of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division,

5th Corps. He selected

Norton as his brigade bugler and headquarters flag bearer.

This assignment later provided Norton with the basis for his 1913

book

The Attack and Defense of Little Round Top, Gettysburg, July 2, 1863.

The volume related how Vincent led his brigade during the contest

for the critical hill.

Norton reviewed the written accounts of historians and official reports,

and he wrote to field officers, including Army of the Potomac commander,

Maj. Gen. George G. Meade and Gouverneur K. Warren, who served as a

brigadier and Meade's chief topological officer during the battle.

Norton also communicated with the Army of Northern Virginia Corps

commander, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet about the fighting from the

Confederate perspective.

Norton matched their accounts to what he had witnessed.

He concluded that Vincent acted on his own initiative, without a

direct order from his division commander, Brig. Gen. James Barnes to

move his brigade to Little Round Top.

Had Vincent failed, he could have faced court-martial.

Norton's book has since become the definitive work on the subject

and a Civil War classic, and today remains required reading at West

Point, as well as many foreign military academies.

In September 1889, veterans of the 83rd returned to Little Round Top for

the dedication of their Associations' monument which included at its top

a bronze sculpture of Vincent drawing his sword.

Norton delivered the dedication speech at the reunion.

He also sounded Taps for the occasion.

Norton later recalled "That familiar sound echoing amongst the

rocks where they (the 83rd veterans) had fought back, perhaps more

vividly than the words could do the memories of that day when they

answered so often to its sound.

Up the hill, the vets came, many with wet eyes, asking to hear it

repeated."

During the war, Norton wrote 150 letters, mostly to his sister,

Elizabeth Lane Norton in Chautauqua, New York.

According to family, she had helped runaway slaves, escaped to

Canada. Norton published

his writings in a book for his family in 1903.

Army letters, 1861 - 1865 detailed his many battles, rendering

valuable insights into a soldier's thinking and duties during the war.

In a letter dated October 15, 1863 Norton disclosed to his sister that

in the previous May he had started studying for the officer's

examination because he "could not be contented as a brigade bugler when

there was a possibility of doing better."

A month later, he informed her, "I am half 'luny' with delight...

because I am 'First lieutenant, 8th Regiment, United States Colored

Troops.'"

Norton did not mention that if Confederates captured him, his standing

as a white officer in a black regiment could result in hardship or

death. The possibility of

cruel treatment did not deter him from his commitment.

On February 8, 1864, Norton led Company K of the 8th into battle

at Olustee, the largest engagement fought in Florida during the war.

He informed his sister with grim detail, that the regiment did

not perform well. His

letter, however, also expressed his admiration for the courage of his

troops. "Color bearer after

color bearer was shot down and the colors seized by another... (finally)

the battery was captured and our colors with it... Company K went into

the fight with fifty-five enlisted men and two officers.

It came out with twenty-three and one officer.

Of these, but two men were not marked.

That speaks volumes for the bravery of Negroes.

Several of these twenty-three were badly cut, but they are

present with the company.

Ten were killed, four reported missing, though there is little doubt

that they are killed too...

A flag of truce from the enemy brought the news that prisoners black and

white were treated alike. I

hope that it is so, for I have sworn never to take a prisoner if my men

who were left there were murdered."

Norton described to his sister his brush with death during the fight.

"Well, you are wanting to know how I came off, no doubt.

With my usual narrow escapes, but escapes.

My hat has five bullet holes in it. Don't start very much at that

- they were made by one bullet. You know that the dent in the top of it.

Well, the ball went through the rim first and then through the

top in this way. My hat was

cocked up on one side so that it went through in that way and just drew

the blood on my scalp. Of

course, a quarter of an inch lower would have broken my skull, but it

was too high. Another ball

cut away a corner of my haversack and one struck my scabbard.

The only wonder is I was not killed, and the wonder grows with

each succeeding fight, and this is the fifteenth or sixteenth... Had

anyone told me when I enlisted that I should have to pass through so

many, I am afraid it would have daunted me.

How many more?"

Norton wrote his mother about the 8th. "I think another fight will give

them a different story to tell."

He attributed the loss at Olustee to inadequate training and

failures of commanding General Truman Seymour.

President Lincoln, too, shared his comments on the battle, remarks that

seemingly concurred with Norton's opinion.

"There have been men who have proposed to me to return to slavery

the Black warriors of Port Hudson and Olustee to their masters to

conciliate the South. I

should be damned in time and eternity for doing so."

Olustee was Norton's last battlefield combat.

Soon afterwards, he was appointed regimental quartermaster and

later advanced to the brigade level.

His duty seems to kept him behind the lines.

In December 1864, he declined the captaincy of his company on

health grounds. The final

tally of the battles in which he participated was 27.

He wrote "There is something grand in the way Honest Old Abe is steering

the ship of state through the breakers of revolution."

In August 1864, the 8th moved to Virginia and the Richmond-Petersburg

siege theater, where it joined the Army of the James.

The regiment performed gallantly, as he had suggested it would,

in several actions, including Deep Bottom, Chaffin's Farm, Darbytown

Road, and Fair Oaks. While,

at Chaffin's Farm, Norton wrote to his father about the Confederacy.

"The power that opposes us is just as steadily crumbling away...

when the bells of peace ring out over the land, we shall have thrown the

last spade full of earth on the bloody carcass of slavery, autocracy of

color, States rights, and all the demons of that ilk that have troubled

us so long."

Five years after the war, Norton married a fellow church member, Lucy

Coit Fanning. They raised

five children, with four surviving to adulthood.

They name one son Strong Vincent in honor of the Little Round Top

hero. Norton became a close

friend of his late colonel's widow, Elizabeth (Lizzie) Carter Vincent.

In 1913, she gave her husband's sword to Norton's son Strong, who

declined the honor. The

sword was instead presented to the Smithsonian Institute's National

Museum of American History.

It remains there today, but not on display, as originally stipulated in

the gift agreement. A year

later, Lizzie died. Her

will gifted $250 to Norton "to be expended on the best cigars he can

buy." He instead donated

the money to a black church in Cincinnati.

In 1870, Norton joined his younger brother Edwin in a

manufacturing venture in Chicago.

The firm prospered, and in 1901, their company became part of

American Can Company.

Norton spent his final 26 years as a blind man.

He died in 1920. He

and his heirs endowed several worthwhile institutions that exist to this

day.

We now once again pick up the story of Daniel Butterfield.

While serving on Hooker's staff, he devised a system of using

different shapes for corps badges.

These badges, which were distinctive shapes of colored cloth sewn

into uniforms were used to identify the many units in the US Army.

Corps badges first appeared by the order of General Philip

Kearney after he had mistakenly reprimanded officers from a different

command than his. When

Hooker assumed command of the army of the Potomac, he assigned

Butterfield to develop the shapes to be used.

Butterfield knew the importance of recognition of units by

special identifying marks.

After all, he wrote his own bugle call so he could use it to stop

confusion on the battlefield and to identify his troops.

The system he devised was clever in its simplicity.

Corps would be identified by shapes, including these: A disc for

First Corps, a trefoil for Second Corps, a lozenge for Third Corps. A

triangle for Fourth Corps and the Maltese cross for Fifth Corps.

The Maltese cross was chosen by him because of his fondness for

the shape which he had used for metals to decorate his men of the 12th

New York Militia before the war.

Divisions would be identified by the color of the shape.

Red for First Division, white for Second, blue for Third, green

for Fourth, and orange for Fifth.

These shapes were chosen by Butterfield for, as he wrote, "no

reason other than to have some pleasing form or shape, easily and

quickly distinguish from others, and capable of aiding in the “esprit de

corps," and elevation of the morale and discipline of the army..."

These badges soon proved to be very popular within the army.

Severely wounded at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863, by cannon fire that

preceded Picket's charge but he did not retire from active field service

until he fell victim to fever during Sherman's March to the Sea.

He was reassigned to the western theater.

By war's end, he was breveted major general in the regular army

and stayed in the army after the Civil War, serving as superintendent of

the Army's General Recruiting Service in New York City and colonel of

the Fifth U.S. Infantry.

While superintendent of the recruiting service, he ordered a board of

officers convened to examine a fife and drum music manual (Strube's

Drum and Fifth Instructor)

for its fitness for adoption by the U.S. Army.

This was his Special Orders No. 21, dated February 13, 1869.

He also approved this board's acceptance of the manual and then

forwarded to the Secretary of War, who authorized its use by appropriate

units of the U.S. Army.

General Daniel Butterfield was involved with military music, although

this time it's for fife and drum.

Butterfield was honored by being selected to present the flags of

the regiment of New York State troops to the governor of New York at the

end of the war.

After his distinguished military career Butterfield was reassigned from

the army in 1870 to serve in the Treasury Department under President

Ulysses S. Grant. He later

went back to work for the American Express Company and became a

prominent businessman. When his father passed away in 1869, Butterfield

cared for the large estate that the family inherited.

He was in charge of numerous special ceremonies, including the

funeral of General William Tecumseh Sherman in 1891.

Among his achievements was the building of a railroad in

Guatemala, and serving as president of the Albany and Troy Steamboat

Company, head of Butterfield Real Estate Company, and president of the

National Bank of Cold Spring.

In London, England, in September 21, 1886, Butterfield married Julia

Lorillard James of New York.

Butterfield's first wife, whom he married in 1857, died in 1877.

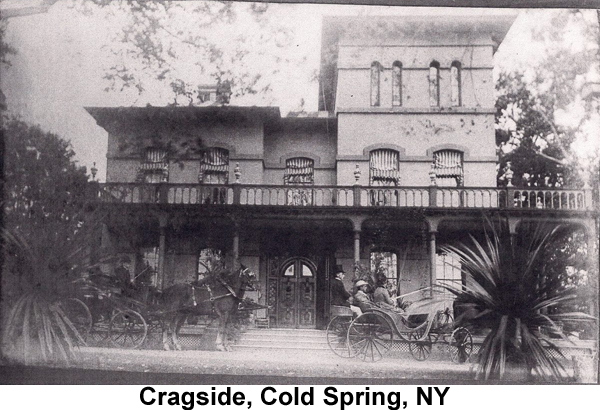

He retired to Cragside, his country home in Cold Springs, New

York overlooking the Hudson River.

The town of Cold Springs got its name from a spring from which

George Washington frequently drank.

The home became a place that entertained many foreign

dignitaries. In the

evening, Butterfield could hear the West Point bugler sounding Taps just

across the river.

Butterfield died on July 17, 1901 and was buried by special order of the

Secretary of War in the cemetery at the U.S. Military Academy at West

Point with full military honors.

His tomb is the most ornate in the cemetery at West Point despite

the fact that he never attended.

There is also a monument to Butterfield in New York City near

Grant's Tomb. There is

nothing on either monument that mentions Taps or Butterfield's

association with the call.

Taps was sounded at his funeral.

Butterfield kept no diary of his Civil War experiences and the

only recollections of his military life come from official records,

speeches, and writings made many, many years after the war.

A

Biographical Memorial of General Daniel Butterfield Including many

Addresses and Military Writings

was written.

How did Taps became associated with funerals?

The earliest official reference to the mandatory use of Taps at military funeral ceremonies is found in the U.S. Army

Infantry Drill Regulations of 1891, although it had doubtless been used

unofficially a long time before that time under the former designation

“Extinguish Lights.”

use of Taps at military funeral ceremonies is found in the U.S. Army

Infantry Drill Regulations of 1891, although it had doubtless been used

unofficially a long time before that time under the former designation

“Extinguish Lights.”

The first use of Taps at a funeral occurred in 1862 during the Peninsula

Campaign in Virginia.

Usually, three volleys were fired during a military burial service.

This practice originated in the old custom of halting the

fighting to remove the dead from the battlefield.

Once each army had cleared its dead, they would fire three

volleys to indicate that the deceased soldiers had been cared for and

that the army was ready to resume the fight.

The tradition of firing three volleys at funerals was noted in

regulations and manuals. In

modern day ceremonies the fact that the firing party consists of seven

riflemen firing three volleys does not constitute a 21-gun salute; that

is only rendered by cannon firing 21 times.

During the Peninsula Campaign, Captain John C. Tidball of Battery A,

Second Artillery lost a cannoneer who was killed in action.

This soldier then needed to be buried at a time when the battery

occupied an advanced position concealed in the woods.

Since the enemy was close, Tidball realized that it was unsafe to

fire the customary volleys over the grave.

He worried that the volleys would renew fighting.

It occurred to Captain Tidball that the sounding of Taps would be

the most appropriate ceremonies to use as a substitute.

He ordered it sounded during the burial.

The practice thus originated was taken up throughout the Army of

the Potomac and finally confirmed by orders.

The first sounding of taps at a military funeral is commemorated in a

stained-glass window at the Chapel of the Centurion, the Old Post

Chapel, at Fort Monroe, Virginia.

The window was designed by Colonel Eugene Jacobs and made by R.

Geissler of New York. It

was based on a painting by Sidney King.

The window was dedicated in 1958 and depicts a bugler and a flag

at half-staff. In the

painting, a drummer boy stands beside the bugler.

The grandson of that drummer boy purchased Berkeley Plantation,

where Harrison's Landing is located.

Berkeley Plantation was a home to more than 100,000 men of the army of

the Potomac. For 45 days

during the summer of 1862.

First settled in 1619 by Englishman, Berkeley acquired its other name

from the Harrison family, who built the stately mansion in 1826.

The Harrisons of Berkeley plantation included Benjamin Harrison

and William Henry Harrison.

Benjamin Harrison, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, lived

from 1726 to 1791. William

Henry became the 9th president of the United States.

He had a home in North Bend, Ohio, where grandson Benjamin

Harrison was born. This

second Benjamin Harrison was the great grandson of the Benjamin Harrison

who signed the Declaration of Independence.

This younger Benjamin Harrison, who lived from 1833 to 1901

became the 23rd president of the United States.

As with many other customs, the solemn tradition of sounding Taps

continues today. Although

Daniel Adams Butterfield merely revived an earlier bugle call, his role

along with Oliver Wilcox Norton in producing these 24 notes gives these

men a place in the history of music as well as the history of war.

Last changed: 03/01/25 |