The President’s Message:

Did you ever wonder what became of the generals who survived the Civil

War? Did they go back

to the occupations that they had before the War?

Did they start new

careers? Janell

Bloodworth and I present a program entitled “Generals and What They Did

After the War.” The

research was very interesting, and we hope that you find it interesting

too.

Gerridine LaRovere

May 8, 2024:

Ken Corhan delivered a program about General Henry Wager Halleck who has

been described as a man completely lacking in physical attractiveness or

charm-pop-eyed, flabby, surly, and crafty.

He had the reputation for being one of the most unpopular men in

Washington, D.C. during the Civil War.

The

presentation began with a list of eleven generals from the Civil War.

Ken began by asking for a show of hands of who thinks a given

leader is competent or incompetent.

How about Joe Hooker. competent or incompetent?

He proceeded down the list from William Rosecrans, George Thomas,

DC Buell, John Pope, William Tecumseh Sherman, James Longstreet, PGT

Beauregard, William Hardee, Braxton Bragg, to Jubal Early.

They were all at West Point at the same time as Henry Halleck.

Interestingly, Ulysses Grant was a Fourth Year, a plebe, in 1839

just after Halleck graduated. The

presentation began with a list of eleven generals from the Civil War.

Ken began by asking for a show of hands of who thinks a given

leader is competent or incompetent.

How about Joe Hooker. competent or incompetent?

He proceeded down the list from William Rosecrans, George Thomas,

DC Buell, John Pope, William Tecumseh Sherman, James Longstreet, PGT

Beauregard, William Hardee, Braxton Bragg, to Jubal Early.

They were all at West Point at the same time as Henry Halleck.

Interestingly, Ulysses Grant was a Fourth Year, a plebe, in 1839

just after Halleck graduated.

For all the attention that anyone even remotely related to the Civil War

gets, Henry Halleck, who had a pretty important position, gets little;

there's just not much written about him.

The first real biographical study that Ken came across was by

Stephen Ambrose. In 1962,

Ambrose published a book focused on Halleck’s wartime experiences that

was essentially an expansion of his master's thesis.

The basic resource for Ken’s talk was a book entitled

Commander of All Lincoln's Armies: A Life of General Henry W. Halleck

by John F. Marszalek, a well -known Civil War historian.

Marszalek’s career was at Mississippi State University.

He is mainly noted for his research on Sherman and Grant.

As a matter of fact, he served for many years as the Executive

Director and Managing Editor of the Ulysses S. Grant Foundation,

retiring just in 2022. Among his many honors, in 2018 Marszalek received

the Nevins-Freeman Award, the most prestigious honor given by the CWRT

of Chicago. Because Sherman

and Grant had so many run-ins with Halleck and he realized that Halleck

didn't have much of anything of substance written about him, Marszalek

just took it upon himself to write Halleck's biography.

Henry Wager Halleck was born in western New York in 1814 which at that

time was a frontier area.

His father was a strict disciplinarian, and young Henry rebelled against

him. He actually ran away

from home when he was 17 and was taken in by his maternal grandfather

and uncle. The Wagers

supported him as a young man.

When he showed an academic disposition, they sponsored him into

several local academies in upstate New York and finally into Union

College. At the first

academy he attended, he called himself H. Wager because he was so angry

with his father. Soon

thereafter, though, he mellowed just a little bit, and throughout his

academic career and for a time thereafter, he signed himself out as H.

Wager Halleck.

He was admitted to West Point in 1835 and excelled.

He would end up graduating third in his class with only 16

demerits. He was a student

of and influenced heavily by Dennis Hart Mahan, a professor of

engineering and strategy.

Mahan was viewed as the premier eminent strategic thinker at the

Academy. While Halleck was

still a cadet, he was asked to be assistant professor of chemistry.

He also tutored incoming freshmen in math.

(At the time, the USMA accepted students as young as 15.

All they were required to do was be able to read, write basic

grammar, and have some facility with arithmetic.

Halleck was among the cohort that provided necessary tutoring to

incoming plebes who needed that support.)

After he graduated, he was asked to stay on as an assistant

professor of engineering under Mahan.

He really enjoyed the experience and the academic structure of

mathematics and engineering.

In April 1840, he was assigned to New York and Washington, D.C.

He performed significant engineering duties at the New York

harbor under the command of an older officer who was in bad health.

This provided an opportunity for Halleck to really assert

himself. He examined the

fortifications and found them wanting.

Halleck designed improvements, oversaw their construction, and

documented everything. He

authored a number of books and articles which brought him favorable

attention. A lot of his

writings were compilations, but before the Internet compilations were

important resources for anyone researching a complex subject.

In 1843, he was able to get a leave of absence to take a short trip to

France. He met some of the

more senior and important generals and was even introduced to King Louis

Philippe. He returned to

New York in 1844. The next

year, largely because of his earlier writings, he was asked to speak at

the Lowell Institute in Boston, a very prestigious invitation.

Halleck gave 12 lectures on military art.

These lectures were later collected and published in book form

becoming known as the

Elements of Military Art and Science.

His lectures and book were again largely a compilation of other

people's writings, but such compilations (especially if annotated) were

very helpful and popular among students of the particular subject

matter. His book was very

well received, and it became standard reading for anyone who wanted to

make a career in the military.

Halleck was 32 years old at the outbreak of the Mexican-American War in

1846. Halleck wanted to be given some sort of combat responsibility.

After some wait, he was assigned (along with William Sherman,

believe it or not) to ship out to California which was part of Mexico.

They went on a supply ship, and they took the 6-month long route

around Cape Horn. Not long

after he arrived, Halleck was given the post of Secretary of State by

the military district commander, Colonel Richard Mason.

He performed his duties well in the area of

organization and research (here, especially of Spanish and

Mexican land title documentation).

When he was younger, he had complained about bureaucracy, but he

really was himself turning into the consummate bureaucrat.

to be given some sort of combat responsibility.

After some wait, he was assigned (along with William Sherman,

believe it or not) to ship out to California which was part of Mexico.

They went on a supply ship, and they took the 6-month long route

around Cape Horn. Not long

after he arrived, Halleck was given the post of Secretary of State by

the military district commander, Colonel Richard Mason.

He performed his duties well in the area of

organization and research (here, especially of Spanish and

Mexican land title documentation).

When he was younger, he had complained about bureaucracy, but he

really was himself turning into the consummate bureaucrat.

As noted, at this time California belonged to Mexico.

At first, Halleck arranged to continue the general civil

administration through the alcaldes, the Mexican appointed mayors of the

small towns and administrative centers, while implementing the new

territory-wide authority of the American military governor.

In October of 1847, Halleck got his wish for a combat assignment

and became part of a military unit traveling in a three-ship flotilla,

under Commander William Schubert, that sailed to Baja California.

There, he engaged in some small unit military maneuvers and led

several of them successfully.

He showed bravery and enterprise and came back very well

respected by his commander.

He then turned his attention, once again, to his Secretary of State

duties.

This was a military administration, of course, under which Halleck

prepared a code of laws to administer the new territory.

Interestingly, about this time, he was offered a professorship at

Harvard, but he turned it down because he felt he was needed in

California to help stabilize the organization and administration of the

new territory.

There was a strong popular movement to bring California into the Union

as a state, but Congress was dragging its heels.

Congress moved very, very slowly with regard to the admission of

new states because of the hotly contested issue as to whether the

applicant territory should be a free or a slave state. The national

debate on this issue led to the Compromise of 1850, a tattered solution

whose many problems contributed to the crisis of 1860.

And all through this, Halleck was very protective of his career.

A naval officer who had heard about and read some of his writings

wanted to meet him, but he came away describing him as selfish, covetous

of renown, unfriendly, jealous of any naval doings, but called him an

officer of ability, very brave, and energetic

In early 1849, a new governor, General Bennet Riley, was appointed.

Acknowledging the local political movement in favor of statehood,

Riley saw himself as a transitional caretaker standing in for an

ultimate civilian government.

As such, he called for a Constitutional Convention, which was

enthusiastically received by almost all of the American residents.

Halleck was the sole military representative at the Convention.

He was very important because of his administrative experience as

Secretary of State, because of his research, knowledge, and organization

of the existing land title process, and because he spoke Spanish, as

well as French and English.

He quickly became a very prominent and influential participant in the

Convention process.

While he was anti-slavery, Halleck was very racist.

He actually joined a group that unsuccessfully argued to keep

blacks out of California.

One of the big side issues

at the Convention related to slavery was the location of the

Territory’s eastern boundary.

Halleck took a position that he wanted the boundary to be pushed

as far east as possible. He

was looking for the Rockies to be the natural boundary because he was

hopeful that, if it was, the slavery debate would be taken out of

California politics and out of the politics of the American territories

west of the Rockies.

However, this was an unsuccessful argument, and the Sierra Nevada became

California’s eastern boundary.

For his work at the Convention, Halleck received high praise from

Governor Riley. When the

Constitution was finally adopted, it was enthusiastically received, and

crowds came out and showered many of the participants, including

Halleck, with shouts of approval.

In accepting the praise of the crowd, Governor Riley took time to

say that the Constitution’s creation and adoption could not have been

accomplished without the help of Halleck.

Interestingly, when, as part of the process of California

becoming a state, the legislature appointed two senators to serve in the

U. S. Senate, Halleck came in third in the voting losing out to John C.

Fremont and William Gwin.

Halleck had read a little bit of

law during his time in the Army, and he knew a lot about land titles in

California because of his work while Secretary of State.

He had translated many of them and had set up procedures for

recognizing the old land title documents from the previous Spanish and

Mexican administrations.

Largely as a consequence of this background, he was asked to become part

of a three-man law firm, Halleck, Peachy, and Billings.

The law firm did a lot of land litigation, as you can imagine.

Land and land titles were a major source of contention in the new

state. The new Americans

wanted to push out the land claims of the Mexicans, and the Mexican land

claims were not always well documented.

Naturally, these disputes led to a lot of litigation and

significant legal fees. And

then there were opportunities for land speculation.

For example, Halleck on his own bought 30,000 acres in Marin

County which he sold off from time to time, adding to his growing

wealth.

San Francisco in the early days was built out of wood.

Not surprisingly, there were a lot of fires and San Francisco

burned down several times.

The three law partners decided they would build an office complex

sturdier than just wood.

They picked a full city block of land that they called “Washington

Block.” They looked to

invest $3 million in the project.

The land itself cost $100,000, a significant amount of money back

then. The building was

built on marshy land.

Halleck, being an engineer, sought out an architect to plan something a

little bit out of the ordinary, a floating foundation.

The project took two years to complete.

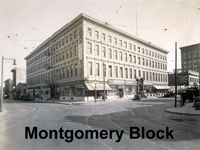

It became known as the “Montgomery Block" and was the center of

much commercial activity in San Francisco for many years.

A

quick word about the Montgomery Block.

The floating foundation was ridiculed by a number of people at

the time of its construction.

However, the building withstood the 1906 earthquake, probably

because of the floating foundation, and avoided the wrecker’s ball until

the mid-1950’s. During its

life, the Montgomery Block offices housed such notables as Bret Harte,

Mark Twain, Jack London, and Frank Norris. A

quick word about the Montgomery Block.

The floating foundation was ridiculed by a number of people at

the time of its construction.

However, the building withstood the 1906 earthquake, probably

because of the floating foundation, and avoided the wrecker’s ball until

the mid-1950’s. During its

life, the Montgomery Block offices housed such notables as Bret Harte,

Mark Twain, Jack London, and Frank Norris.

In 1854, Halleck decided to go to New York to see if he could find a

young lady to marry. He had

always been interested in the ladies, but that interest was not always

returned. That year,

however, he proposed to the younger sister of his West Point roommate, a

lady by the name of Elizabeth Hamilton (who happened to be the

granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton).

They got married in the spring of 1855 and returned to San

Francisco.

While he was in the law firm, the partners tried doing a lot of

different things; some things turned out well and others not so much.

In addition to the Montgomery Block, they tried building a short

railroad which went bust pretty quickly.

They got involved in a quicksilver (mercury) mine.

Quicksilver was very important at the time in the processing of

gold. Halleck became the

general manager for a mercury mine that became the subject of much

contentious litigation.

Even the US government took some interest in it.

The Feds sent an attorney, Edwin Stanton (yes! that Edwin

Stanton), to investigate.

Halleck and Stanton did not have a very good relationship.

Stanton thought that Halleck was a man of low integrity and

thought Halleck actually committed perjury on the stand in connection

with some of the litigation connected to the mine.

During the crisis of 1860, Halleck stood very firmly for the Union.

In December of 1860, he was appointed a Major General in the

California militia. He

generally had a very low view of the militia because he felt militias

were always poorly trained.

But he applied himself to the disorder.

You can see that over the course of his life he is good when his

responsibilities are those of support, logistics, and administration.

He will prove to be a great administrator but a horrible field

commander. Time and again,

he will fail as an ultimate strategic commander to show the initiative

or even responsibility for the placement and movement of troops

necessary for a successful outcome in the field.

Early on in the war, Lincoln appointed him as a Major General, at the

time the highest rank one could have in the Army.

And actually, he had people on his side (including then

Commanding General of the Army, Winfield Scott) arguing that he should

be the commanding general of the whole Army, but instead that command

went to Major General George McClellan.

His first big assignment was in the West where he replaced the

incompetent and corrupt John Fremont in St. Louis.

He was very popular at first.

Missouri was a border state, and Lincoln was very, very careful

not to offend slave owners in the border states because he did not want

to lose those states to the Confederacy.

Fremont, along with his other miscues, had angered Lincoln when

he emancipated all the slaves of the supporters of the Confederacy

within his military jurisdiction.

The President quickly reversed that action.

Sherman was under Halleck’s command.

Sherman and Halleck had had a huge falling out when they were

both in California.

(Incidentally, Sherman had run a bank in California where Halleck's wife

had worked as a clerk.)

Sherman had a bit of a bumpy time at the beginning of the war.

Many people thought him insane.

His command was taken away from him.

But Halleck, despite his bad feelings back in California,

actually treated him kindly and supported him coming back into the Army

in a command position. One

reason, certainly, was that Sherman's father-in-law, Thomas Ewing, was a

very powerful political figure.

Again, Halleck was always sensitive to which way political winds

are blowing.

In early 1862 Lincoln wanted aggressive military action.

None of his senior generals shared this enthusiasm including both

Halleck and McClellan. But

Halleck did have a strategic plan to take Forts Henry and Donelson on

the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers although he took no meaningful

action to implement this plan.

Grant had formed a similar strategic plan on his own.

He went to Halleck with his plan, but Halleck pretty much

dismissed him out of hand.

Meanwhile, Lincoln was becoming increasingly frustrated with the

inaction of his generals.

And in January, he issued orders to his generals and said he wanted them

to take aggressive action by George Washington's birthday.

Except for Grant and his naval commander, Andrew Foote, none of

the other field commanders paid any real attention to Lincoln’s order.

Grant and Foote kept pushing Halleck while Halleck was also being

pushed by Lincoln. So it

was that Halleck gave permission for Grant to attack Forts Henry and

Donelson. Grant captured

Fort Henry on the 7th

of February, captured Fort Donaldson on the 16th,

and the whole north-facing Confederate defensive position built by

Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston pretty much fell apart.

Halleck seemed to be doing a lot.

Of course, it was not so much Halleck as it was his subordinates.

Lincoln and even Stanton are looking favorably on what Halleck

seemed to be doing.

Halleck, even before Shiloh, had made a decision that he was going to

mass Buell’s and Grant’s armies under his direct field command and move

on Corinth. But before he

could do that, Shiloh happened.

Grant has received a lot of criticism for Shiloh because of the

great loss of life and because he was caught by surprise on the first

day of the battle.

Notwithstanding that, he was able to restore the fighting confidence of

his troops and to organize and coordinate his reinforcements to achieve

a startling victory the next day.

Sherman, who was totally unprepared for the initial attack,

rallied the troops the next day and turned back the Confederates helping

to achieve a great victory that just the night before seemed like an

unmitigated disaster.

Indeed, General P.T.G. Beauregard, had sent news to Confederate

President Jefferson Davis after the first day’s fighting that the

Confederates had won a great victory.

However, in the end, Albert Sidney Johnston was killed in the

battle, and the Confederates had to fall back to Corinth.

Halleck was loath to give Grant much credit.

Indeed, as Halleck masses the armies under his command, he made Grant his second-in-command, in effect taking Grant out

of the fighting. And

consistent with his military strategy, instead of attacking the

Confederate defenders the way Grant or Sherman would have done,

Halleck’s strategy was all about moving slowly from behind daily

constructed entrenchments and fortifications.

Halleck outnumbered the Confederates 100,000 to 66,000 but his

dilatory tactics allowed pretty much the whole 66,000 Confederate force

to escape pretty much unscathed, even though Corinth was taken with

little bloodshed. Grant

would later severely criticize the Corinth campaign in his memoirs.

The illustration on the right is a Currier & Ives done in 1861.

By the end of the war the guys in front would have been moved

back.

command, he made Grant his second-in-command, in effect taking Grant out

of the fighting. And

consistent with his military strategy, instead of attacking the

Confederate defenders the way Grant or Sherman would have done,

Halleck’s strategy was all about moving slowly from behind daily

constructed entrenchments and fortifications.

Halleck outnumbered the Confederates 100,000 to 66,000 but his

dilatory tactics allowed pretty much the whole 66,000 Confederate force

to escape pretty much unscathed, even though Corinth was taken with

little bloodshed. Grant

would later severely criticize the Corinth campaign in his memoirs.

The illustration on the right is a Currier & Ives done in 1861.

By the end of the war the guys in front would have been moved

back.

In the spring, after all of Lincoln’s prodding, McClellan finally makes

his move on the peninsula.

It was initially successful but, in the end as we know too well, he was

thrown back by Lee. Even

before the Seven Days, Halleck was made co-equal with McClellan.

Stanton and Lincoln were acting as commanding generals, but, in

July, Lincoln went further and appointed Halleck as the supreme

commander of the Union Army.

Also at this time, General John Pope was given command of an

eastern army but had not yet pulled together all of his forces.

Lincoln wanted McClellan to link up with Pope, but Halleck could

not bring himself to give McClellan such a direct order.

Consequently, McClellan (purposefully?) dawdled and failed to

support Pope in time to make any difference in the upcoming battle

between Pope and Lee.

The summer was not going well for the Union. The Union was again facing

a series of defeats.

Without support from McClellan, Pope was ignominiously defeated.

There were more defeats in September.

Lincoln had to swallow his pride and asked McClellan to take

control of the Army of the Potomac again.

The great battle of Antietam took place on September 17th.

It was the bloodiest day of the war despite the fact that

McClellan had full access to

Lee’s battle plans.

Once again, although Lee eventually abandons the field, McClellan, with

his superior numbers, will not pursuit him.

It went from bad to worse with Burnside at Fredericksburg in December

and Hooker at Chancellorsville in May.

Now into the summer of 1863, the only commander who had really

accomplished anything was Grant at Vicksburg.

Immediately before Grant’s capture of Vicksburg, General George

Meade, newly appointed commander of the Army of the Potomac, had success

at Gettysburg where he defeated Lee, but he, too, refused to pursue Lee.

After the July victories, Lincoln fired some senior commanders,

but he continued to rely on Halleck even as he was becoming increasingly

frustrated with Halleck’s lack of initiative and failure to exhibit

effective command over his subordinates in the field.

Halleck from the very beginning, and all through the war, demonstrated a

decided refusal to take any strategic responsibility for the conduct of

the war. He repeatedly told

Lincoln it was not his place to second guess and to give a direct order

to a commanding general in the field.

Interestingly, Grant and Sherman were both quite ready to

conceive and initiate bold actions to the strategic suggestions/approval

of Halleck with requiring him to issue specific orders.

Not surprisingly, they were all of a sudden Halleck’s favorite

generals; he just couldn’t say enough nice things about them.

Congress and Lincoln, too, were enthralled by Grant’s and

Sherman’s successes and took action to promote Grant to the rank of

Lieutenant General, a rank previously held only by George Washington and

Winfield Scott.

With Grant’s promotion, Halleck became his Chief of Staff, a position in

which he would receive much success.

Now, he could focus on coordinating the provision of supplies and

ammunition as well as other logistic support to the armies in the field.

And, as he had shown earlier in his career, he was very good at

that. In addition, he and

Grant worked well together.

He was not jealous of Grant.

He didn't hold grudges against Grant.

And, with few exceptions, he always spoke highly of Grant.

After the war, Halleck was first given command of the Military Division

of the James, headquartered in Richmond, and, only a few months later

(arguably because of his blatant racism) he was transferred to command

of the Military Division of the Pacific, headquartered in San Francisco,

where he was instrumental in the incorporation of Alaska as an American

territory. Four years later

he was transferred to command the military Division of the South,

headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky.

Here, he faced a lot of white resistance.

The Ku Klux Klan was active, but Halleck took little or no

aggressive actions against them, showing again his sympathies with white

supremacist positions. Some

of his actions (or lack of action) have been attributed to his being

ill. He had complained of

some chronic illnesses as early as when he was in his 30s.

There were some allegations that Halleck was affected by opioid

medicines that were prescribed for him for chronic hemorrhoids and by

overuse of alcohol to ease his discomfort from the withdrawal symptoms

he suffered in connection with his opium medicine.

It all came to a head in 1872.

His health deteriorated to such an extent that he was pretty much

bedridden for the last months of his life.

Henry Halleck died in his bed about a week prior to his 58th

birthday.

Last changed: 05/25/24 |