Volume

28, No. 3 – March 2015

Volume 28, No. 3

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President’s Message

Please pay your dues! Your dues pay the rent at

the Scottish Rite Hall, pay for guest speakers and the out-of-pocket

costs of the Newsletter and refreshments. Dues are $40.00 and can be

paid to Steve Seftenberg at a meeting or mailed to him at 2765 White

Wing Lane, West Palm Beach, FL 33409. If you would like to give a

program, please contact me – (561) 967-8911 or e-mail

honeybell7@aol.com.

Gerridine LaRovere, President

March 11, 2015 Program

Robert O’Neill’s talk will be on Jeb Stuart’s Christmas Raid of

December 1862 and is drawn from his 2012 book, Chasing Jeb Stuart and

John Mosby, The Union Cavalry in Northern Virginia from Second Manassas

to Gettysburg. Stuart’s earlier raids in June and October 1862 had

humiliated Gen. George McClellan and his Army of the Potomac. On his

Christmas Raid he would encounter the troops assigned to the Defenses of

Washington, rather than the Army of the Potomac. Stuart would not enjoy

the success of his earlier raids, but his audacity nonetheless left a

lasting mark on the Union psyche. Bob will discuss both the raid and the

most important, but largely unrecognized, result. Bob also published

Small But Important Riots, The Cavalry Battles of Aldie, Middleburg and

Upperville in 1993, has published many articles in Blue & Grey,

North & South and Gettysburg Magazine and has guided numerous

tours of the cavalry battlefields in the Louden Valley, Virginia. We can

look forward to an exciting trip.

February 11, 2015 Program

Bob Schuldenfrei introduced us to the first use of telegraphy in

wartime – a real 19th Century "information revolution." Bob’s primary

sources included Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails (2006), by Tom Wheeler,

Chair FCC, Military Telegraphy During the Civil War ... (1882),

by William Plum, and Lincoln in the Telegraph Office (1907) by

David Homer Bates. Plum was Gen. George H. Thomas’ telegrapher and Bates

was one of the four operators of the U. S. Military Telegraph Corps.

Both were expert in this new field. Wheeler’s thesis was that before the

telegraph the speed of communication at its fastest was the speed at

which a horse could run. With the small exception of signal flags or

fires the "iron law" of communication was that distance delayed delivery

of information. Almost overnight, the telegraph overturned this law by a

lightning stroke!

Prologue and the First Telegram of the War: The "hardware" of

telegraphy goes back to the 1830's with Morse and others; its "software"

is the coded information sent over wires, pioneered by railroads who

could string up the lines in their right-of-ways. The keys to long

distance telegraphy included wire insulation, powerful batteries, poles

with glass insulators and relays that boosted the signal’s strength. The

first telegraph customers were lottery "sharps" and stock brokers who

scored by getting advance knowledge of lottery numbers or trades on the

Philadelphia stock exchange. An early legitimate use were the six

newspapers who organized the "Associated Press." By 1861 the lines had

crossed the continent and businesses were quick to use the wires to sell

their products. Remember the business card, "Have Gun, Will Travel -

wire Paladin, San Francisco?" Railroad companies soon found that

telegraph dispatch dramatically reduced wrecks on single track lines.

Once dispatch was widespread, other uses soon took hold: scheduling,

inventory control, ordering, planning, etc. The first telegram of the

war was sent by Gen. Pierre Gustav Toutant Beauregard on April12, 1861,

not to Jefferson Davis in Montgomery, Alabama, but to the U. S. War

Department: "Gen. Beauregard to the Secretary of War. Charleston, April

12, 1861. We opened fire at 4.30 minutes." The next day, Beauregard

telegraphed Davis, "Quarters in Sumter all burned down. White flag up.

Have sent a boat to receive surrender..."

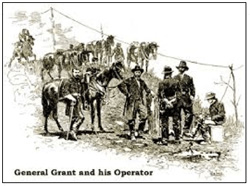

Use of Telegraphy in Battle and in Strategy: As the war

progressed, the wire followed the troops. The story can be told by

looking at the personal styles of four men: Abraham Lincoln, George

McClellan, Edward Stanton and Ulysses S. Grant. Lincoln may have been

slow to adopt the new technology but learned to use it effectively to

establish a modern management structure to conduct the war to victory.

McClellan’s sudden rise to power was due to his sophisticated use of

telegrams to enlarge small victories into "great triumphs." Eventually

Grant would be able to command all theaters of war from his location

with Meade’s army in Virginia.

Operating

the telegraph networks was split in at least three ways: First came

private companies like the American Telegraph Company, Western Union

Telegraph Company and Southwestern Telegraph Company. The Union Army had

the Signal Corps, whose job it was to disseminate intelligence. As the

war began, it tried to commandeer wire communications, but was beaten

out by the United States Military Telegraph Corps ("USMTC"). After Fort

Sumter, Secretary of War Simon Cameron recruited Thomas A. Scott of the

Pennsylvania Railroad, who was given the rank of Colonel and on April

19, 1861, he commandeered the telegraph offices in Washington. The first

new line connected the War Office with the Navy Yard. Lincoln’s call for

75,000 troops on April 15, 1861, went out by telegraph. On February 26,

1862, Lincoln took possession of all telegraph lines and put them under

the control of the USMTC. Operating

the telegraph networks was split in at least three ways: First came

private companies like the American Telegraph Company, Western Union

Telegraph Company and Southwestern Telegraph Company. The Union Army had

the Signal Corps, whose job it was to disseminate intelligence. As the

war began, it tried to commandeer wire communications, but was beaten

out by the United States Military Telegraph Corps ("USMTC"). After Fort

Sumter, Secretary of War Simon Cameron recruited Thomas A. Scott of the

Pennsylvania Railroad, who was given the rank of Colonel and on April

19, 1861, he commandeered the telegraph offices in Washington. The first

new line connected the War Office with the Navy Yard. Lincoln’s call for

75,000 troops on April 15, 1861, went out by telegraph. On February 26,

1862, Lincoln took possession of all telegraph lines and put them under

the control of the USMTC.

The South’s Superior Use of the Telegraph in the First Battle of Bull

Run Leads to Victory: The North’s telegraph line inexplicably halted

at Fairfax Courthouse, leaving a gap between there and McDowell’s army.

Worse, Gen. Paterson, in Harper’s Ferry, was also "off the grid" and

could not quickly be ordered to support McDowell. In contrast,

Beauregard telegraphed the South’s Secretary of War, who relayed the

message to Joe Johnston in the Shenandoah Valley to move most of his

troops to Manassas. This permitted the South to pull off a very

difficult military maneuver – to get three groups, separated by many

miles, to converge on a single spot, if not instantly, certainly far

quicker than the Northern armies. A fatal result for McDowell was that

as the battle joined, he no longer had a larger army. Bob noted that

both sides tried the strategy of converging forces to obtain numerical

advantage, the side successfully utilizing the telegram usually won.

McClellan’s

Star Rises: On July 8, 1861, in what is now West Virginia, McClellan

sent his troops forward to meet the rebels at Rich Mountain. McClellan’s

staff worked closely with the telegraph service and when the battle was

won by General Rosecrans on July 11th, McClellan’s telegram reported,

"Our success complete and almost bloodless," which greatly elated the

North. He also issued a congratulatory order to his troops using a

portable printing office for the first time in the field. Clearly, old

George understood public relations. His telegram secured McClellan’s

reputation as a "winning" general and a "Young Napoleon" and quickly led

to his appointment by a shaken but not panicky Lincoln by telegram as

commander of the Army of the Potomac on the day after First Bull Run.

That same day Lincoln signed the bill calling for 500,000 troops to

serve for three years. McClellan shone as a superb organizer, taking a

collection of dispirited men to form a cadre to which he added raw

recruits as they showed up. He got rid of bad officers, installed

discipline and pride in "his" troops who repaid him with admiration they

felt for no other Northern general. Prior to embarking on the

"Peninsular" campaign, McClellan organized a "corps d’ armee," led by

five generals of modest abilities, whose job it was to open and protect

communication over the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, guard Maryland and

Pennsylvania from surprise attack by the rebels and, if needed, to help

defend Washington. Halleck was in overall command. Thus there was unity

of command assured by good telegraphic communications. This should have

allowed theater concentration of force to overwhelm the South, but for

Stonewall Jackson who was sent North by Lee. McClellan’s

Star Rises: On July 8, 1861, in what is now West Virginia, McClellan

sent his troops forward to meet the rebels at Rich Mountain. McClellan’s

staff worked closely with the telegraph service and when the battle was

won by General Rosecrans on July 11th, McClellan’s telegram reported,

"Our success complete and almost bloodless," which greatly elated the

North. He also issued a congratulatory order to his troops using a

portable printing office for the first time in the field. Clearly, old

George understood public relations. His telegram secured McClellan’s

reputation as a "winning" general and a "Young Napoleon" and quickly led

to his appointment by a shaken but not panicky Lincoln by telegram as

commander of the Army of the Potomac on the day after First Bull Run.

That same day Lincoln signed the bill calling for 500,000 troops to

serve for three years. McClellan shone as a superb organizer, taking a

collection of dispirited men to form a cadre to which he added raw

recruits as they showed up. He got rid of bad officers, installed

discipline and pride in "his" troops who repaid him with admiration they

felt for no other Northern general. Prior to embarking on the

"Peninsular" campaign, McClellan organized a "corps d’ armee," led by

five generals of modest abilities, whose job it was to open and protect

communication over the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, guard Maryland and

Pennsylvania from surprise attack by the rebels and, if needed, to help

defend Washington. Halleck was in overall command. Thus there was unity

of command assured by good telegraphic communications. This should have

allowed theater concentration of force to overwhelm the South, but for

Stonewall Jackson who was sent North by Lee.

Jackson Outmaneuvers two Northern Generals and Frustrates McClellan’s

Grand Plan. Jackson first defeated Fremont at McDowell, Virginia on

May 8, 1862, freezing Fremont. He then faked moving East to reinforce

Johnston and headed up the Shenandoah Valley where together with Ewell

he trounced Banks at Front Royal on May 23rd. The next day he captured a

treasure trove of supplies (leading to Banks’ derisive nickname of

"Commissary Banks") and on May 25th, he won again at Winchester. Banks

pulled back and Lincoln sent Gen. Irwin McDowell to aid him in the

Valley. Only then did Jackson head for the Peninsula, leaving behind

Northern forces totaling about 60,000 troops that "could have/should

have" helped McClellan to enter Richmond but for Jackson’s audacity. How

effective this was is shown by a telegram to McClellan from Lincoln (not

Halleck) saying, "In consequence of General Banks’ critical position I

have been compelled to suspend General McDowell’s movement to join

you..." McClellan was not pleased.

Lincoln’s "Electronic Breakout:" With this telegram to McClellan,

in what Wheeler calls his "Electronic Breakout," Lincoln dramatically

changed the way he exercised his leadership. There was no

"general-in-chief" (Halleck was AWOL). Instead, the "commander-in-chief"

took to the wires, projecting his personal authority into the field,

using his instincts, natural abilities as a leader and rapid student of

war. The technology lengthened his long arm of command. This was the day

the universe changed. The telegram informed the public, taught Lincoln

how to take command and taught the Northern military how to implement

Lincoln’s commands from a distance.

Informing the Public: Unlike First Bull Run, reporters were on

the scene beginning in March 1862. In February an underwater cable had

been laid from Fort Monroe to the tip of the Eastern Shore of Virginia

and thence to the War Department. The Army paid for the construction but

traffic on this line was available to the news outlets, including the AP

and The New York Times. One of the earliest communiqués was a

truly "live" report from George Cowlam on March 9, 1862, of the damage

inflicted by the CSS Virginia: "She is steering straight for the

Cumberland" – a pause – "The Cumberland gives her a

broadside" – anxious watching – "She has struck the Cumberland

and poured a broadside into her. God! The Cumberland is sinking!"

– breathless suspense – "The Cumberland has fired her last

broadside." The next day, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and the

whole nation learn of a major shift in naval warfare with a real time

account by telegraph of the action between the USS Monitor and

the CSS Virginia: G. V. Fox, Assistant Secretary to Welles:

"These two ironclads fought part of the time touching each other, from 8

a. m. until noon, when the Merrimack retired. Whether she is

injured or not is hard to say. . . . The Monitor is uninjured and

ready at any moment to repel another attack." From now on, Northern

citizens will learn about the events of the war at almost the same time

as their leaders.

Command at a Distance: Until April 1, 1862, the only telegraphic

traffic was between McClellan and the Army headquarters in Washington.

Lincoln monitored the messages but remained silent. McClellan’s messages

are lengthy and flowerily, but one example suffices to show his shocking

lack of good intelligence about his enemy: With an army of 80,000 men,

"I must attack in position, probably intrenched [sic] a much

larger force, perhaps double my numbers." (Emphasis added)

Lincoln, who was famous for what is now called "management by walking

around." takes a boat to Fort Monroe where he was livid to learn that

McClellan had sat before Yorktown. Lincoln took off his stovepipe hat

and slammed it to the ground. He alone and not the army commander

ordered a successful attack on Norfolk which led to the scuttling of the

CSS Virginia. Lincoln sailed back to Washington a changed man.

McClellan missed this sea change in his commander and continued to wire

for more troops. Lincoln, who was as brief as McClellan was verbose,

replied to one 10-page telegram with "I am still unwilling to take all

of our forces off the direct line between Richmond and here."

On May 24, 1862, Lincoln sent nine telegrams (more in one day than he

had sent in total up to that time) to his far-flung commanders: Fremont,

McDowell, McClellan and Saxton. As the battle progressed, McClellan

whined that he was in no way responsible for his defeat; it is all

Lincoln’s fault. As the army retreated, Halleck and McClellan engage in

a shouting match by telegram. Halleck: "come home." McClellan: "Army is

in great position to take Richmond." Halleck: ". . . withdrawal order

will not be rescinded." McClellan: "Why not reinforce me here?"

McClellan: "I do not have enough ships." While McClellan used the

telegraph effectively with his subordinates, his strategic goal failed

because he was ineffective in the field. No amount of telegrams, however

long, could convince Lincoln and Halleck to see things his way.

McClellan Leaves Pope in the Lurch; Haupt Comes to Lincoln’s Aid:

McClellan "slow walks" toward Bull Run because he did not want to see

Pope score a big victory. He even all but disobeys a direct order to go

to Pope’s aid. On August 26, 1862, Jackson destroys the massive supply

dumps at Bristol Station and Manassas Junction and in the process cuts

the line between Pope and Washington. The best information Lincoln could

get was from Col. Herman Haunt, in charge the railroads, especially the

telegraph line along the track bed of the Orange & Alexandria RR.

Lincoln and Haupt then exchanged telegraphic messages much like texting

in a chat room today. Despite the bitter loss at Second Bull Run,

Lincoln was impressed by Haunt and promoted him to Brigadier-General of

Volunteers "for meritorious services in the recent operations . . . near

Manassas."

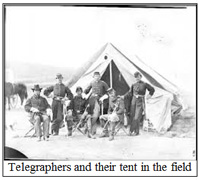

Telegraphy

in the West; Civilian Heroes: Telegraph communication was vastly

more difficult in the western theater – distances are greater, railroad

tracks are less plentiful and protecting the wires from sabotage was a

real challenge. Also, much of the fighting was along the rivers, which

made installing lines impractical and the North’s western generals did

not yet appreciate the advantage of using telegraphy in battle

management. Instead, the use of courier dispatches to the nearest

telegraph station produced a hybrid of old and new technologies. Even

Washington did not learn of the fall of Fort Donelson until the day

afterward. Grant’s reputation grew, in part because of his famous

statement to Confederate General Bruckner, "No terms except an

unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted." Grant’s use of

"unconditional surrender" was not original – both Admiral Foote (at Fort

Henry) and Brig. Gen. Smith (at Fort Donelson) had already used it. As

the war moved south along the Tennessee River, the telegraph followed

(from Paducah to Fort Do nelson and then south). The men who laid and

maintained the wires were civilians and therefore got little credit and

their widows got no benefits. George H. Smith kept mounted repairers at

each station who rode their circuits daily. This was very hazardous

duty. Plum wrote that the man who responds promptly to a call to repair

a broken line in a guerrilla-infested region has a degree of courage

rarely required in actual battle. Telegraphy

in the West; Civilian Heroes: Telegraph communication was vastly

more difficult in the western theater – distances are greater, railroad

tracks are less plentiful and protecting the wires from sabotage was a

real challenge. Also, much of the fighting was along the rivers, which

made installing lines impractical and the North’s western generals did

not yet appreciate the advantage of using telegraphy in battle

management. Instead, the use of courier dispatches to the nearest

telegraph station produced a hybrid of old and new technologies. Even

Washington did not learn of the fall of Fort Donelson until the day

afterward. Grant’s reputation grew, in part because of his famous

statement to Confederate General Bruckner, "No terms except an

unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted." Grant’s use of

"unconditional surrender" was not original – both Admiral Foote (at Fort

Henry) and Brig. Gen. Smith (at Fort Donelson) had already used it. As

the war moved south along the Tennessee River, the telegraph followed

(from Paducah to Fort Do nelson and then south). The men who laid and

maintained the wires were civilians and therefore got little credit and

their widows got no benefits. George H. Smith kept mounted repairers at

each station who rode their circuits daily. This was very hazardous

duty. Plum wrote that the man who responds promptly to a call to repair

a broken line in a guerrilla-infested region has a degree of courage

rarely required in actual battle.

Grant had excellent communications with Halleck until he reached

Shiloh, which is on the other side of the river and therefore was cut

off from Halleck until a wire was laid across the river after the

battle. Since the wire was several feet too short, L. D. Parker set up

shop on a tree trunk leaning over the river; a limb held his letter

clip, cipher book and paper, sending and receiving while being harassed

by mosquitoes. Buell also had excellent communications with Halleck and

with Washington. A telegram from Halleck to Buell makes the point:

"Events are pressing so rapidly that I must be in telegraphic

communication with Curtis, Grant, Pope and Commander Foote. We must

consult by telegraph."

Fuller’s Field Glasses and Revolver: Time for some comic relief:

George A. "Lightning" Ellis, a Kentucky telegrapher, joined Morgan’s

raiders. He was to send telegrams for Morgan, both real and fake. Morgan

was never a strategic threat to the Union but he did tie up a number of

Federal troops who futilely chased him around. He belongs here because

of his communications with William G. Fuller, a USMTC supervisor. Near

Lebanon, Kentucky, Morgan pounced on Fuller’s wagon and took his navy

revolver, new boots, fur cape, gloves and fine field glasses. Six months

later, Morgan walked into the telegraph office in Somerset, Kentucky and

sends a telegram to George D. Prentice, the editor of the newspaper in

Louisville. Fuller heard of this and sent a telegram to Morgan, saying,

"General, I am informed that you have my field glasses and pistols ...

Please take good care of them." Morgan responds, "Yes, I have your field

glasses and pistols. They are good ones and I am making good use of

them. If we both live til the war is over, I will send them to you."

Alas, Morgan did not survive the war; he was killed during a raid on

Greenville, Tennessee.

Gettysburg:

Lincoln knew Lee was "going North" as well as Lee’s troop strength,

movement and position after Pleasanton’s cavalry engages Stuart’s

cavalry near Charlottesville. Everything the Union screeners learn was

sent at near lightning speed to Washington. Not only can Lincoln warn

the Northern states of Lee’s movements but the Northern newspapers also

keep their readers informed. In contrast, Lee does not know where the

Union army is or where it is headed. Doris Kerns Goodwin, in Team of

Rivals (2005) states Lincoln was a constant fixture at the telegraph

office, even napping there, before and during the Battle of Gettysburg.

Lincoln’s anxiety grew as his communications with his generals became

intermittent. But as the Union army moved Northward, it crossed rail

line after rail line, each of which had telegraph stations so

intelligence and orders could be transmitted promptly to and from

Washington. While the Union army is still well South of Lee’s army,

Union cavalry haunted Lee’s right flank. Then Lee commits a colossal

blunder by allowing Stuart to take a joyride around the State of

Pennsylvania. Thanks to a Confederate spy, Lee finally learns that he

must order his scattered units to converge on Gettysburg. The Northern

wires are humming with military traffic but the newspapers are getting

nothing, on purpose. Unlike previous engagements, Meade had telegraphic

communication with his corps and divisional commanders during all three

days of the battle. However, having the telegraph and using it

effectively turned out to be two different things. At the height of

Sickles’ foolish advance, Gen. Gouverneur Warren went on horseback to

persuade Gen George Sykes to send a brigade double-timing to the crest

of Little Round Top just in time to blunt the charging rebels. For once,

a horse and not the telegraph was the communications vehicle of choice

that day. Gettysburg:

Lincoln knew Lee was "going North" as well as Lee’s troop strength,

movement and position after Pleasanton’s cavalry engages Stuart’s

cavalry near Charlottesville. Everything the Union screeners learn was

sent at near lightning speed to Washington. Not only can Lincoln warn

the Northern states of Lee’s movements but the Northern newspapers also

keep their readers informed. In contrast, Lee does not know where the

Union army is or where it is headed. Doris Kerns Goodwin, in Team of

Rivals (2005) states Lincoln was a constant fixture at the telegraph

office, even napping there, before and during the Battle of Gettysburg.

Lincoln’s anxiety grew as his communications with his generals became

intermittent. But as the Union army moved Northward, it crossed rail

line after rail line, each of which had telegraph stations so

intelligence and orders could be transmitted promptly to and from

Washington. While the Union army is still well South of Lee’s army,

Union cavalry haunted Lee’s right flank. Then Lee commits a colossal

blunder by allowing Stuart to take a joyride around the State of

Pennsylvania. Thanks to a Confederate spy, Lee finally learns that he

must order his scattered units to converge on Gettysburg. The Northern

wires are humming with military traffic but the newspapers are getting

nothing, on purpose. Unlike previous engagements, Meade had telegraphic

communication with his corps and divisional commanders during all three

days of the battle. However, having the telegraph and using it

effectively turned out to be two different things. At the height of

Sickles’ foolish advance, Gen. Gouverneur Warren went on horseback to

persuade Gen George Sykes to send a brigade double-timing to the crest

of Little Round Top just in time to blunt the charging rebels. For once,

a horse and not the telegraph was the communications vehicle of choice

that day.

A Logistical "Miracle" Saves the Day: Following Gen. William

Rosecrans's defeat at Chickamauga on September 19, 1863, the Union was

in despair – if it had not been for "Pap" Thomas’ stand the Union army

could have been destroyed. Ironically, it was a reporter, Charles Dana,

who was in the field, who wired for help. Stanton and the Northern

railroad and telegraph men were pivotal in moving two Union brigades

from Virginia 1,233 miles to Tennessee by rail in only 12 days! In

Lincoln’s war council, on September 23, 1863, Halleck had estimated this

move would take three months while Maj. Thomas Eckert, the senior

telegrapher present, reduced this figure to forty days and in a written

report the next day reduced it further, to 15 days. Actually it took

only 12 days! The true heroes of this tale are Eckert, John Garrett of

the B&O, and Maj. Gen. Daniel Craig McCallum, Director of the Department

of Military Railroads in the War Department (an early management pioneer

who developed the first modern organizational chart) who took over

military control of all railroads on the route west. Eckert ingeniously

suggested using coal barges as pontoon bridges, ready in 24 hours. He

also proposed that a force of cooks and waiters be placed at "eating

stations" every 50 miles or so along the route. As a train reached an

eating station, they would board the train, feed the troops en route,

get off at the next eating station and return to their original position

by train to do it over. McCallum took over military control of all

railroads on the route. Stanton sent a blizzard of telegrams with orders

and questions. This episode is an excellent case study of management

planning and follow through.

Lincoln Spared the Lives of Scores of Young Men: Of the more than

1,000 telegrams Lincoln sent out during the war, the majority of them

involved suspension of executions. Without the telegraph, the

President’s power of pardon would have been to late to save lives. In

one example, he spared the life of a Confederate spy being held in Fort

Monroe. In another, he spared the life of an underage deserter named

August Bittersdorf, saying, "I am unwilling for any boy under eighteen

to be shot; and his father affirms that he is yet under sixteen."

Lincoln also delayed numerous executions so that all possible avenues of

review could be exhausted. Over 500 soldiers were executed during the

war, of which 276 were Union troops. The vast majority of executions

were for violent criminal offenses, although by 1864 the number of

executions for desertion was increasing as commanders both North and

South faced increasing desertion rates.

At the conclusion of his talk, Bob received a warm round of applause

for explicating a little known topic.

Last changed: 02/19/15

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|