Vol. 22 No. 4- April 2009

Volume 22, No. 3

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

NOTE CHANGE OF DAY AND DATE DUE TO PASSOVER

April Program

Colonel Jack Travis will present an in-depth study on the five flags

of the Confederacy. He will explain why men on both sides fought and

died for their flags. Come hear the Rebel Yell and see the Bonnie Blue

flag.

President's Message

If your dues are not paid by the end of the April

meeting, this will be the last newsletter that you will

receive and you will not be included in the 2009 directory. Your dues

pay for our meeting expenses and donations. There are openings for

speakers. If you would like to give a program, please let me know.

Remember to sign up for refreshments at the meeting. Cash donations are

also appreciate for the forage fund. It is with regret that I have

to say that Stuart Robinson passed away in February. We extend our

condolences to his family.

Gerridine La Rovere, President

Program: Wednesday, March 11, 2009

March biography:

Member

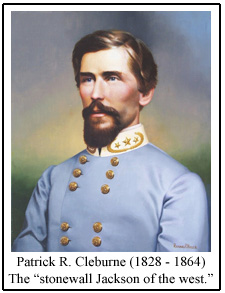

Camille Granda introduced us to Patrick Romayne Cleburne.

Cleburne was born in Ireland. Orphaned at 15, he failed entrance exams

at Trinity Medical College; enlisted in the 43rd Regiment of the English

army where he rose to the rank of corporal. He purchased his discharge;

emigrated to Helena, Arkansas, where he became a pharmacist and a

lawyer, and became a US citizen in 1860. He went with the South solely

out of affection for his neighbors. He was elected captain of the Yell

Rifles; seized the US arsenal at Little Rock in 1861; his unit was added

to the 1st (later renamed the 15th) Arkansas Infantry Regiment; he was

elected Colonel and on March 4, 1862, Brig. General. His motto: Duty

Points the Way. Fought at Shiloh, Richmond, Kentucky (where he was

wounded in the face); promoted to command a Division in Arkansas; at

Stone River, his troops advanced 3 miles; promoted to Major General

12/13/62. Led a night assault at Chickamauga and fought rear guard

actions at Missionary Ridge and at Ringold Gap, Georgia that saved the

Confederate Army from disaster. His ability to utilize terrain to

advantage and to hold ground led to his nickname, "the Stonewall of the

West." Federal troops dreaded seeing his blue flag on the battlefield.

He felt that "slavery was not the sole reason for the war, only a

pretext for centralized government." His recommendation to draft and

emancipate blacks as soldiers in the army led to a fierce backlash in

the South. He soldiered on: outnumbered 4-to-l, he blocked Sherman at

Chattanooga and harassed Sherman’s advance through Georgia. Sent to

Kentucky, he was killed leading an ill-conceived attack he opposed at

Franklin, Kentucky on November 30, 1864, and was buried there (his

remains were later moved to Helena). Cleburne, a brilliant leader,

served under less competent generals and as a result got less attention

than he deserved. Sadly, he became engaged in 1864 but was killed before

he could marry. Member

Camille Granda introduced us to Patrick Romayne Cleburne.

Cleburne was born in Ireland. Orphaned at 15, he failed entrance exams

at Trinity Medical College; enlisted in the 43rd Regiment of the English

army where he rose to the rank of corporal. He purchased his discharge;

emigrated to Helena, Arkansas, where he became a pharmacist and a

lawyer, and became a US citizen in 1860. He went with the South solely

out of affection for his neighbors. He was elected captain of the Yell

Rifles; seized the US arsenal at Little Rock in 1861; his unit was added

to the 1st (later renamed the 15th) Arkansas Infantry Regiment; he was

elected Colonel and on March 4, 1862, Brig. General. His motto: Duty

Points the Way. Fought at Shiloh, Richmond, Kentucky (where he was

wounded in the face); promoted to command a Division in Arkansas; at

Stone River, his troops advanced 3 miles; promoted to Major General

12/13/62. Led a night assault at Chickamauga and fought rear guard

actions at Missionary Ridge and at Ringold Gap, Georgia that saved the

Confederate Army from disaster. His ability to utilize terrain to

advantage and to hold ground led to his nickname, "the Stonewall of the

West." Federal troops dreaded seeing his blue flag on the battlefield.

He felt that "slavery was not the sole reason for the war, only a

pretext for centralized government." His recommendation to draft and

emancipate blacks as soldiers in the army led to a fierce backlash in

the South. He soldiered on: outnumbered 4-to-l, he blocked Sherman at

Chattanooga and harassed Sherman’s advance through Georgia. Sent to

Kentucky, he was killed leading an ill-conceived attack he opposed at

Franklin, Kentucky on November 30, 1864, and was buried there (his

remains were later moved to Helena). Cleburne, a brilliant leader,

served under less competent generals and as a result got less attention

than he deserved. Sadly, he became engaged in 1864 but was killed before

he could marry.

March book review:

Member

Ed Lewis discussed James McPherson’s new book, Trial By War: Abraham

Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief. McPherson, who won a Pulitzer Prize

for his Battle Cry For Freedom, focused on Lincoln’s growth as

military Commander-in-Chief. Few Presidents have acted as

Commander-in-Chief, leaving battlefield strategy and tactics to the

generals and admirals, and in the beginning Lincoln (whose only military

experience was two months in the Blackhawk War) followed the same

pattern. Once faced with war, however, he read many books. He stumbled

in the early months and made many "bad" appointments (out of the

mediocre group he could chose from until "stars" developed). While his

generals viewed the war as to conquer territory, Lincoln’s native genius

led him to see that the Confederate armies had to be utterly defeated if

the Union was to be preserved. He quickly saw the advantages the

telegraph and the railroad gave the Union forces and often slept at the

War Department telegraph office. As his confidence grew, his advice and

orders to his generals became more sophisticated. A similar earlier book

is T. H. Williams, Lincoln and His Generals (1952). Lincoln

finally found generals, such as Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, who were

aggressive and smart. Lewis recommended reading both these books. Member

Ed Lewis discussed James McPherson’s new book, Trial By War: Abraham

Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief. McPherson, who won a Pulitzer Prize

for his Battle Cry For Freedom, focused on Lincoln’s growth as

military Commander-in-Chief. Few Presidents have acted as

Commander-in-Chief, leaving battlefield strategy and tactics to the

generals and admirals, and in the beginning Lincoln (whose only military

experience was two months in the Blackhawk War) followed the same

pattern. Once faced with war, however, he read many books. He stumbled

in the early months and made many "bad" appointments (out of the

mediocre group he could chose from until "stars" developed). While his

generals viewed the war as to conquer territory, Lincoln’s native genius

led him to see that the Confederate armies had to be utterly defeated if

the Union was to be preserved. He quickly saw the advantages the

telegraph and the railroad gave the Union forces and often slept at the

War Department telegraph office. As his confidence grew, his advice and

orders to his generals became more sophisticated. A similar earlier book

is T. H. Williams, Lincoln and His Generals (1952). Lincoln

finally found generals, such as Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, who were

aggressive and smart. Lewis recommended reading both these books.

March program

Member Marsha Sonnenblick’s lavishly illustrated

lecture, US Medical Service Through Five Wars, used the device of taking

one young man and giving him a similar wound in each war. First is

Robert Forbes, in 1856, a 14-year old farm boy living in York,

Pennsylvania and an avid reader. At that time, Jefferson Davis, the US

Secretary of War, sent a committee (including McClellan) to study the

English medical service as well as English and Russian military tactics

in the Crimean War. The Civil War was fought in the last stages of

medieval medicine – American medical schools were a joke: it took no

qualification (except the ability to pay the fee) to attend or to

graduate. The US Army had about 100 surgeons, few of whom were

qualified. Drs. William Hammond and Jonathan Letterman served in the

West. During the war, over 11,000 surgeons were used by the North

(compared to about 3,000 by the South). Many doctors, many of whom had

never done an operation, rushed to join the army. The first part of Mrs.

Sonnenblick’s talk is limited to the Army of the Potomac in the early

stages of the war. Forbes joined the 39th Pennsylvania Regiment in June

1861.

A "minie" ball could go through several bodies and

become easily infected. Most wounds as a result led to amputation (by

the end of the war, 50,000 plus amputations were performed!). The

"surgeon" sharpened his implements on his shoe, wiped it off on his long

coat, and never washed his hands. 95% of surgeries used a light does of

chloroform, which the South had little of (in one incident, Phil

Sheridan provided Confederate doctors chloroform so they could operate

on Confederate soldiers captured by his troops). Mortality rates varied

by the location of the amputation: hands and fingers (26%), shoulder

(30%), upper arm (24%).

Forbes

was wounded in the leg but laid out on the battlefield for three days

before being brought to the medical tent. He was in shock and his wound

was infected. The surgeon botched the amputation. Forbes was sent to

Washington, DC, but died 30 days after he was wounded. Another soldier

wrote: "A rebel ball shattered my right knee. I lay for two days and

when I was finally taken in, my accommodations were meager: no chamber

pot (which made diarrhea hard to handle) and no heat (at least the cold

weather reduced the maggots!). A nurse wrote in her diary, a wounded

soldier recovered from pneumonia and diphtheria but died anyway.

Frederick Law Olmstead wrote to his wife: 2 or 3 soldiers accompanied

200 wounded soldiers on the train -- no straw, "festering" and "awful

stench" (called "patriotic smell!). Olmstead was moved to instigate the

creation of the Sanitary Commission. In 1862, typhoid was rampant

(victims included Stephen Douglas and President Lincoln’s son) and

caused two-thirds of all deaths. The dead were embalmed by private

entrepreneurs ($7 for a soldier and $13 for an officer). Forbes

was wounded in the leg but laid out on the battlefield for three days

before being brought to the medical tent. He was in shock and his wound

was infected. The surgeon botched the amputation. Forbes was sent to

Washington, DC, but died 30 days after he was wounded. Another soldier

wrote: "A rebel ball shattered my right knee. I lay for two days and

when I was finally taken in, my accommodations were meager: no chamber

pot (which made diarrhea hard to handle) and no heat (at least the cold

weather reduced the maggots!). A nurse wrote in her diary, a wounded

soldier recovered from pneumonia and diphtheria but died anyway.

Frederick Law Olmstead wrote to his wife: 2 or 3 soldiers accompanied

200 wounded soldiers on the train -- no straw, "festering" and "awful

stench" (called "patriotic smell!). Olmstead was moved to instigate the

creation of the Sanitary Commission. In 1862, typhoid was rampant

(victims included Stephen Douglas and President Lincoln’s son) and

caused two-thirds of all deaths. The dead were embalmed by private

entrepreneurs ($7 for a soldier and $13 for an officer).

Antietam

marked the first battle at which an organized ambulance service was in

effect. Still, as one New York reporter wrote: hundreds of wounded lie

on the floor of one hospital – long lines of wagons pull up – surgeons

are covered with blood. Hospitals were often staffed by untrained

convalescents, some too weak to handle their duties. The doctors too

often treat female nurses like "dirt." Antietam

marked the first battle at which an organized ambulance service was in

effect. Still, as one New York reporter wrote: hundreds of wounded lie

on the floor of one hospital – long lines of wagons pull up – surgeons

are covered with blood. Hospitals were often staffed by untrained

convalescents, some too weak to handle their duties. The doctors too

often treat female nurses like "dirt."

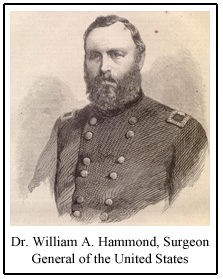

Until Secretary of War Stanton got rid of him, Dr.

William A. Hammond, as Chief of the Union Medical system, reformed the

Army’s hospital and transportation systems. He appointed Dr. Jonathan

Letterman as

Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac. Under Letterman only

doctors with surgical experience could perform surgery. This was the

beginning of medical specialization and the Army’s level of medical

competence grew tremendously under Letterman. He designed supply wagons

organized so supplies could be quickly and easily located. Each doctor

was supplied with a "Squibb Pannier," a smaller box with a variety of

medical supplies. Letterman took ambulances away from the Quartermaster

Corps, launched a "triage" system (I: soon to die; II: needs immediate

attention; and III: can wait) still used today.

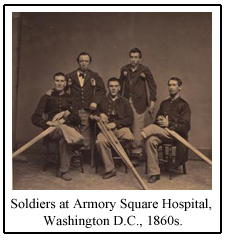

"Hospitals

improved throughout the war. The initial dressing station was usually a

tent, barn, church or private home, where triage and primary surgery

(within 48 hours) was often performed. Surgeons on both sides learned

that their patients fared better when surgery was performed outdoors

rather than indoors, due to improved lighting and ventilation.

Efficiency was gained by building larger hospitals and by creating ward

systems, still in use in some settings, separating patients by injuries

or disease. A growing realization that ‘bad air’ and unclean conditions

might increase infection led to clean, well-ventilated hospitals.

However, direct transmission of bacteria through instruments and

dressing materials went unrecognized. "Hospitals

improved throughout the war. The initial dressing station was usually a

tent, barn, church or private home, where triage and primary surgery

(within 48 hours) was often performed. Surgeons on both sides learned

that their patients fared better when surgery was performed outdoors

rather than indoors, due to improved lighting and ventilation.

Efficiency was gained by building larger hospitals and by creating ward

systems, still in use in some settings, separating patients by injuries

or disease. A growing realization that ‘bad air’ and unclean conditions

might increase infection led to clean, well-ventilated hospitals.

However, direct transmission of bacteria through instruments and

dressing materials went unrecognized.

Our hero, William Forbes, a cousin of Robert, was not

wounded until 1864. An officer, he was shot in the leg at the battle of

Spotsylvania Court House in Wilderness campaign. He was picked up and

taken promptly to a front line hospital tent and then to a hospital in

the rear where his leg was amputated. He was then evacuated by train to

a Washington, DC hospital, or he could have been taken by hospital ship.

He would have been treated by competent doctors and Roman Catholic nuns

acting as nurses. In some cases, Afro-American women acted as nurses.

Hammond redesigned Army hospitals in an arc for efficiency and fresh

air. Each ward had different kinds of wounded. Each had ventilation and

plumbing. Bromine stopped gangrene. Congress in its infinite wisdom

failed to appropriate funds for severely wounded soldiers who were

discharged. After all, they could no longer fight!

The

Confederate Army had its own geniuses: James Hangar designed an

artificial leg with a movable knee. Hangar Co., the company he started

after the war, is still in business. Designing and making artificial

limbs (legs, arms, hands) was a big business after the war. Our hero,

Forbes, fitted with an artificial leg, learned to walk and marched in

many Grand Army of the Republic parades. He married in 1869, had six

children, and died in 1920. The

Confederate Army had its own geniuses: James Hangar designed an

artificial leg with a movable knee. Hangar Co., the company he started

after the war, is still in business. Designing and making artificial

limbs (legs, arms, hands) was a big business after the war. Our hero,

Forbes, fitted with an artificial leg, learned to walk and marched in

many Grand Army of the Republic parades. He married in 1869, had six

children, and died in 1920.

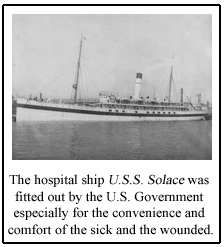

Forbes’ son, William II, fought in the

Spanish-American War. However, despite numerous advances in medical

science, the Army Medical Service failed to further modernize its

organization or treatment between the wars, except for one thing: the

hospital ships returning wounded soldiers and sailors had antiseptic

operating rooms.

William’s

grandson, William III, enlisted in the AEF in World War I. "Luckily" he

was wounded by shrapnel above his knee and not gassed. There were

hospitals near the front lines and the hospital trains carrying the

wounded had operating rooms. There were forward X-Ray units and

gas-driven ambulance trucks. William became a lawyer, married, had three

children, became a state legislator and died in 1975. William’s

grandson, William III, enlisted in the AEF in World War I. "Luckily" he

was wounded by shrapnel above his knee and not gassed. There were

hospitals near the front lines and the hospital trains carrying the

wounded had operating rooms. There were forward X-Ray units and

gas-driven ambulance trucks. William became a lawyer, married, had three

children, became a state legislator and died in 1975.

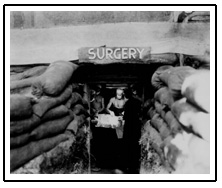

William’s great-grandson, William IV, graduated from law school

before serving 2 1/2 years in the jungles of the South Pacific. In 1944,

he landed with MacArthur on Leyte. Medical corpsmen served alongside

their comrades. They had blood and penicillin. The Geneva Convention,

adopted after WWI, was supposed to protect corpsmen from being shot. The

Germans mostly honored this, but the Japanese made them special targets,

so corpsmen stopped wearing red arm bands. The Army put hospital wards

and operating rooms underground (see picture at right). It flew wounded

soldiers in specially-designed cargo planes (still four bunks on each

side of an aisle, just like the Civil War trains, however). Field

hospitals were established. The one in Manila was located in the

cathedral. Fully-equipped hospital trains and ships were used. Blood

transfusions were common, although typing was not as accurate as it has

become. William IV recovered quickly from his wounded leg, which was

saved, and after the war practiced law, married, joined the VFW and died

in 1997.

Marsha

did not treat the Korean War separately since only five years separated

the end of WWII and the beginning of the Korean War. However,

innovations included "MASH" units: "The MASH unit was conceived by

Michael E. DeBakey and other surgical consultants as the ‘mobile

auxiliary surgical hospital.’ It was an alternative to the system of

portable surgical hospitals, field hospitals, and general hospitals used

during World War II. It was designed to get experienced personnel closer

to the front, so that the wounded could be treated sooner and with

greater success. Casualties were first treated at the point of injury

through buddy aid, then routed through a battalion aid station for

emergency stabilizing surgery, and finally routed to the MASH for the

most extensive treatment. This proved to be highly successful; it was

noted that during the Korean War, a seriously wounded soldier that made

it to a MASH unit alive had a 97% chance of survival once he received

treatment." The unit was later renamed as the "Medical Army Surgical

Hospital." [Editor’s note: Quote from Mobile Army Surgical Hospital,

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.] Marsha

did not treat the Korean War separately since only five years separated

the end of WWII and the beginning of the Korean War. However,

innovations included "MASH" units: "The MASH unit was conceived by

Michael E. DeBakey and other surgical consultants as the ‘mobile

auxiliary surgical hospital.’ It was an alternative to the system of

portable surgical hospitals, field hospitals, and general hospitals used

during World War II. It was designed to get experienced personnel closer

to the front, so that the wounded could be treated sooner and with

greater success. Casualties were first treated at the point of injury

through buddy aid, then routed through a battalion aid station for

emergency stabilizing surgery, and finally routed to the MASH for the

most extensive treatment. This proved to be highly successful; it was

noted that during the Korean War, a seriously wounded soldier that made

it to a MASH unit alive had a 97% chance of survival once he received

treatment." The unit was later renamed as the "Medical Army Surgical

Hospital." [Editor’s note: Quote from Mobile Army Surgical Hospital,

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.]

In Vietnam, William Forbes V, was hit by a "bouncing betty" mine that

nearly severed his right leg above the knee. Front line medics put him

on a medical helicopter which took him to a MASH unit and from there to

a field hospital in Vietnam, then to Japan and then to the Philippine

Islands. He recovered but walked thereafter with a slight limp. In

Vietnam, 70.6% of casualties came from disease, 15.6% from "nonbattle"

wounds (traffic accidents, fights, etc.) and only 17% from actual battle

wounds.

In Desert Storm, William Forbes VI lost his leg to an "IED"

("improvised explosive device") and was equipped with a remote

controlled leg. He was immediately placed in a battlefield ambulance

armored like a tank because of IEDs and reached a forward aid station

within 60 minutes. From there he went to a Combat Support Unit and then

a "Level 4" hospital in Kuwait or Spain or Germany. After extensive

treatment, his final destination was either Walter Reed Hospital,

Washington DC or the big hospital in San Antonio, Texas. Unfortunately

he also suffered traumatic brain damage in the explosion, which left him

with memory loss, mood swings, etc. We are still searching for solutions

to these injuries. Marsha bemoaned the callous lack of support for our

wounded men and women, citing the scandal at Walter Reed Hospital as an

example. Marsha left us with this sobering thought: Many more soldiers

survive their wounds due to superb equipment (kevlar jackets and

helmets, armored vehicles) and advanced medical treatment, but their

wounds are much more severe than in other wars as a result. America will

have an increasingly expensive job on its hands to care for them. She

was somewhat pessimistic about the outcome.

Marsha provided us with a chart showing the relationship between

battle wounds and battle deaths:

|

War

|

Battle wounds

|

Battle deaths

|

Mortality rate

|

|

Revolutionary War

|

10,123

|

4,435

|

42%

|

|

War of 1812

|

6,765

|

2,260

|

33%

|

|

Mexican War

|

5,885

|

1,733

|

29%

|

|

Civil War

|

422,295

|

140,414

|

33%

|

|

Spanish-American War

|

2,047

|

385

|

19%

|

|

World War I

|

257,404

|

53,402

|

21%

|

|

World War II

|

963,403

|

291,557

|

30%

|

|

Korean War

|

137,025

|

33,741

|

25%

|

|

Vietnam War

|

200,727

|

47,424

|

24%

|

|

Persian Gulf War

|

614

|

147

|

24%

|

|

Iraq War (to date)

|

10,369

|

1,004

|

10%

|

Last changed: 06/26/11

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|