The President’s Message:

Our Holiday meeting

will be on December 11, 2019 at 7:00 PM at our new meeting place: Lake

Clarke Shores Town Hall, 1701 Barbados Road, Lake Clarke Shores 33406.

Directions to the Town Hall:

1/ Exit I

95 at Forest Hill Blvd.; go westbound on Forest Hill Blvd.

2/ The

first traffic light is Pine Tree Lane.

Go to the second traffic light which is Florida Mango Road.

3/ Make a

left onto Florida Mango Road.

4/ Proceed

0.1 mile and turn left onto Barbados Road.

5/ Continue on Barbados

Road. Destination is on left.

The Police Building is on right and Town Hall on left.

Our program will be

given by noted author, Robert Macomber.

His topic will be,

Grog, the most famous drink afloat.

Desserts will be

served at the meeting.

Please save some of your appetite for holiday treats.

Please bring any era

history related books or small gift card to your favorite store or

restaurant. We will have a

raffle benefiting the Club for guest speakers.

Dues are due.

Gerridine LaRovere

December 11, 2019 Program:

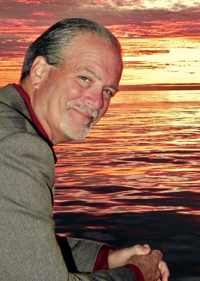

As

is usual for our holiday meeting, we have Robert Macomber back with us

again. Although most of us

are quite familiar with Bob, for our new members he is the author of the

“Honor” series of historical novels.

These books, and there are 15 of them at last count, tell the

story of the late 19th and early 20th century via the

fictional character of Peter Wake, USN. As

is usual for our holiday meeting, we have Robert Macomber back with us

again. Although most of us

are quite familiar with Bob, for our new members he is the author of the

“Honor” series of historical novels.

These books, and there are 15 of them at last count, tell the

story of the late 19th and early 20th century via the

fictional character of Peter Wake, USN.

Robert N. Macomber

has been the recipient of the Patrick D. Smith Literary Award, the

American Library Association’s W.Y. Boyd Literary Award, a Silver Medal

in Popular Fiction from the Florida Book Awards, and a host of other

accolades over two decades.

He has earned rare experiences like being Distinguished Lecturer at NATO

HQs [Belgium], and, for ten years, was invited into the Distinguished

Military Author Series, Center for Army Analysis [Ft. Belvoir].

His topic will be

Grog, the most famous drink afloat.

I have heard this presentation before and it is a winner.

You will learn the history of this libation, learn the fine art

of navy toasting, but sadly you will not get to sample the real stuff.

Town Hall is dry.

November 13, 2019 Program:

The November speaker

was your humble (well perhaps, not so humble) editor.

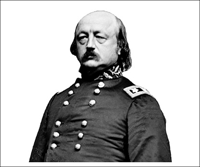

It was a study of the character, and about the character, of

Benjamin F. Butler.

The historical figure of Ben Butler has always been of interest to me.

From the time I first heard about the American Civil War, I

learned that the character of this man was impugned by both North and

South alike. Who was this

evil, incompetent person, who was a leader of men?

For the next hour we investigated Benjamin Franklin Butler.

Besides the Civil

War, Bob has a keen interest in ancient Egypt.

According to Egyptian mythology at death the soul of the deceased has to stand in the Hall of Judgment

before the god Osiris and his fellow gods.

The person’s heart is weighed by Anubis and recorded by Thoth.

Osiris makes no comment.

Then, quivering with fear, the soul watches the god weigh his

heart in the balance. On one

side is his heart. On the

other is the ostrich feather representing Maat, goddess of truth and

justice. If the heart is

found to be neither too heavy nor too light, the dead man is acquitted.

On the other hand, if the heart is found wanting the soul is immediately

devoured. This evening we

are going to judge Benjamin Butler.

at death the soul of the deceased has to stand in the Hall of Judgment

before the god Osiris and his fellow gods.

The person’s heart is weighed by Anubis and recorded by Thoth.

Osiris makes no comment.

Then, quivering with fear, the soul watches the god weigh his

heart in the balance. On one

side is his heart. On the

other is the ostrich feather representing Maat, goddess of truth and

justice. If the heart is

found to be neither too heavy nor too light, the dead man is acquitted.

On the other hand, if the heart is found wanting the soul is immediately

devoured. This evening we

are going to judge Benjamin Butler.

Those who wrote the

history of the war had their reasons for their dislike.

There were obvious dislikes for him in the South.

This was also true for any Union leader like Lincoln, Sherman, or

Grant. What is less obvious

was why Butler was despised in the North.

We will investigate some of his policies that are in favor today,

but not so much in Ben’s period.

He had some attributes that his opponents disliked; many of which

were on display during his life and followed his reputation to the

grave. Besides attributes,

he often stood for unpopular causes.

At the end, we, like Osiris will attempt to pass judgement.

First, and foremost,

Butler was a political “traitor.”

After all, he was a Democrat.

In the North, being a “war Democrats” meant being attacked.

The list was long to include McClellan, Stanton, and even Stephen

Douglas. This last figure

was the very “poster child” for the loyal Democrat.

After losing the election to Lincoln, he professed his support

for his rival and had a seat of honor at the inauguration.

Sadly, Douglas died shortly afterwards.

In 1860 Ben was condemned by the abolitionists.

Rewarded by the Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, Butler became

a general in the United States Army.

This accompanied his appointment to the Board of Visitors at West

Point. During the war, this

was not seen as a plus.

There were three

things against Ben in the North.

First, the DC band was with him when he was on top, but dropped

like a hot stone when he was not.

Secondly, Ben did not go to West Point.

As if to rub it in, he was the youngest major general in the army

at the time he was promoted to that rank.

The “ring knockers” could not stand that.

And finally, it was claimed that old Ben was a terrible general

who did not win any battles.

This is not only false, but it is closely related to the last point.

It was a charge that the regular military often tossed at

political generals. You

might remember my defense of Lew Wallace.

In the South he was

despised for not supporting the “cause.”

In 1860 he attended the Democratic convention in Charleston, SC

as a member of the Massachusetts delegation.

There he supported first Douglas and then Jefferson Davis, who

was running as a moderate.

When the party split, northern members met in Baltimore where he helped

nominate Breckinridge.

In April of 1861 the

6th MA was passing

through that same city on

the way to reinforce Washington.

Mindful, that quick action to isolate the capital might force the

North to let the South go, gangs harassed that unit leaving four

soldiers dead. Butler was on

a ship heading up a force of soldiers when they were ordered to

Annapolis. Maryland governor

Thomas H. Hicks feared that Union troops anywhere in his state would

spark violence, and asked Butler to not put his regiment ashore.

Butler would have none of it.

He landed his troops and secured the railroad from there all the

way to Washington. This

allowed the 7th NY access to DC

which assured the safety of the city.

On April 27th Lincoln suspended

the writ of habeas corpus along the military supply line from

Philadelphia to Washington.

Butler, without orders, took the rest of his command and moved on Relay

House, a rail junction just to the north of Baltimore.

From there he occupied the city and insured the free flow of men

and material from the north to Washington.

After that, Maryland was never a threat to join the Confederacy.

However, General Winfield Scott was not pleased.

After Butler had taken Baltimore, he was the darling of everyone

in Washington except Scott.

When he appeared Butler was forced to stand at attention to report about

his insubordination. The

Lieutenant General broke into angry vituperations over the great and

needless risk Butler had run.

Butler waited, standing before him, until his patience had been

exhausted. Having already

decided to leave the Army if necessary, he turned on the old general and

gave him as good as he got.

History, sadly, has not recorded this “colorful” exchange.

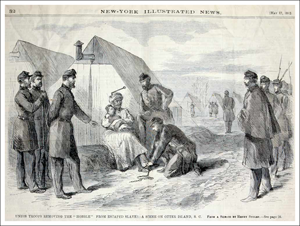

Butler was given

command of Fort Monroe, but Scott reduced Butler’s forces so he could

not go on the offense.

However, he was safe and secure inside the fort.

That fact was not lost on slaves working near the Union lines.

If a slave escaped, Butler would not follow the Fugitive Slave

Law of 1850 which required him to return the slave to his master.

Butler famously claimed that the slaves were not people, but

contraband of war. Like

Baltimore, Ben became a hero in DC when he and Commodore Silas Stringham

took a convoy of six ships and 860 men to Hatteras Inlet, NC.

There they captured two forts and 615 confederates.

This was the first victory since Bull Run.

He was rewarded by being selected to lead forces, together with

Farragut and Porter, against New Orleans. Butler was given

command of Fort Monroe, but Scott reduced Butler’s forces so he could

not go on the offense.

However, he was safe and secure inside the fort.

That fact was not lost on slaves working near the Union lines.

If a slave escaped, Butler would not follow the Fugitive Slave

Law of 1850 which required him to return the slave to his master.

Butler famously claimed that the slaves were not people, but

contraband of war. Like

Baltimore, Ben became a hero in DC when he and Commodore Silas Stringham

took a convoy of six ships and 860 men to Hatteras Inlet, NC.

There they captured two forts and 615 confederates.

This was the first victory since Bull Run.

He was rewarded by being selected to lead forces, together with

Farragut and Porter, against New Orleans.

The Navy got the

better of the forts on the Mississippi delta so the boats sailed on up

river and Butler captured the forts.

Then he joined Farragut sitting in the river with his guns all

aimed at New Orleans. Navy

men raised the American flag over the mint, but the next day

secessionist men hauled it down.

However, with the threat of absolute destruction of the city by

the guns of the fleet, the flag was raised again.

Most all of the citizens of the town were unable to accept

defeat, however, there was little they could do.

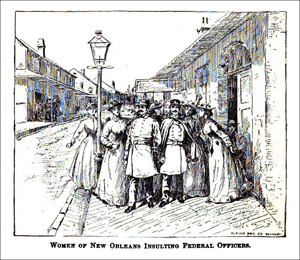

The women of New Orleans were particularly demonstrative in their

contempt for the soldiers.

Farragut was the victim of a chamber pot emptying.

In theory Butler believed in retaliation, but in this case he

pulled back. With the help

of his wife Sarah, Butler issued General Order No. 28 which said: “If

any woman should insult or show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States, she shall

be regarded and shall be held liable to be treated as a woman of the

town plying her avocation.”

The order produced the desired effect, as few women proved willing to

risk retaliation simply to protest the Union presence, but the order was

denounced in the North and the South as harsh.

show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States, she shall

be regarded and shall be held liable to be treated as a woman of the

town plying her avocation.”

The order produced the desired effect, as few women proved willing to

risk retaliation simply to protest the Union presence, but the order was

denounced in the North and the South as harsh.

Ben Butler was a

pioneer in causes that are much in favor today.

We will now discuss these four points.

There is a common theme to them.

They all revolve around the common man.

Butler was a very rich man.

He first made money as a lawyer.

This hard-working young man had just passed the bar in 1840.

His success at the bar, laboring long hours, and choosing his

cases with care led to financial wellbeing and fame.

Many of his cases involved the mills of Lowell, MA.

He represented both sides, one time for the mill owners, another

time for the mill workers.

When a famous mill was on the market, Ben bought controlling interest in

the Middlesex Corporation.

Butler was an

“enlighten” factory owner.

He paid his workers good wages.

This did not endear him to the other owners.

And besides, Ben was a Democrat and they were Whigs or

Republicans. Not only had

Ben defended the 10-hour day in court, he practiced what he preached at

the bar. Rather than being

driven out of business by the competition, his mill made good money.

Now that he was an owner, do you think he gave up taking worker’s

case? He did not.

The workforce was changing about this time.

The “mill girls” were being replaced by the Irish immigrants.

When others would not take their cases, Butler did.

Not only did he have good clients, but he gained good workers and

good voters.

As was noted earlier,

he was in the lead with what we would call integration today.

Not only did he utilize the freedmen during his military service,

he supported the rights of the black man.

In 1866 he successfully ran for the House.

Although it was not popular in the conservative press back home,

Butler fought for equal political rights for Negroes.

In Congress he was the head of the Committee on Reconstruction.

That involvement led to the impeachment of President Andrew

Johnson. He was on the Board

of Managers for the impeachment.

Because of his past activities and skills, he was selected to

lead the prosecution. It is

beyond the scope of tonight’s presentation, but his work at the trial in

the Senate was masterful. He

lost by only one vote.

There is no

disagreement that Butler was smart.

Supporters pointed to this as a plus, detractors would say he was

diabolical. He was called

crafty, clever, crude, and unscrupulous.

Ben had a near photographic memory which was on display from the

time he learned how to talk.

Five months after his birth, his father died of yellow fever.

His mother relied on her own toil and the kindness of relatives.

At age nine, a neighbor wrote to the trustees of Phillips Exeter

suggesting that the school would be wise to offer Benjamin a full

scholarship. Master Butler

matriculated that fall.

However, in spite of good grades, feisty Ben could not help getting into

fights and left both intellectual and physical marks on the institution

and the other students. As a

result, by January he left the school and set out with his mother for

Lowell. He attended public

school in Lowell. He was

almost expelled for fighting.

Next, he attended Waterville (now Colby) College in pursuit of

his mother's wish that he prepares for the ministry, but eventually

rebelled against the idea.

After graduation he read the law which sharpened his already strong

rhetorical skills.

Ben was a workaholic;

no one will deny that. A

positive example of this comes in his first year of practicing law.

Congress just passed the bankruptcy act.

It was clear to him that there would be many cases to try.

So, in addition to his normal workload, he devoted all his free

time, and some of his sleep time, to boning up on the new law.

It paid off handsomely.

In a negative light, Butler quickly gained a reputation as a

dogged criminal defense lawyer who seized on every misstep of his

opposition to gain victories for his clients.

Often these errors were because the lawyer on the other side was

lazy.

Keeping a paper trail

was most important. He kept

meticulous records. While in

New Orleans, Butler was believed by many of personally profiting from

his position. These folks

would have relished the sight of old Ben being brought up on charges.

This never happened because he crossed all his “Ts” and dotted

all his “Is.” For example,

even before he got to New Orleans, he and his force was positioned on

Ship Island at the mouth of the Mississippi ready to attack the forts.

In order to get men and material off the ocean-going ships the

command needed small boats or lighters.

The Navy had captured a blockade runner loaded with $5,000.00

worth of cotton. On the

island the quartermaster’s civilian laborers were almost in a state of

mutiny for lack of pay. He

needed those men and their boats to offload his stuff.

The rules stated that the captured cotton should be sent to

Boston to await adjudication as prize money.

This would have taken months and the money would have gone to the

Navy anyway.

What Ben did was

brilliant, expedient, and probably extra-legal.

Because he documented every step, he was never in legal hot

water; no one even tried.

First, he put the cotton on a ship which was to return to Boston empty.

He consigned the cargo to his own broker, Richard S. Fay, Jr.

Next, he borrowed $4,000.00 from a sutler on the island.

Those funds paid the laborers their wages.

They then offloaded Butler’s ships.

When Fay made the private sale of the cotton, he sent the funds

south and Ben repaid the loan to the sutler.

As much as Benjamin

Butler’s opponents would have wished otherwise, he was honest and could

not be bribed. While this

seems to be true, like so many aspects of his life, it depends on how

historians, you, or Ben look at the facts.

There is no doubt he was, for lack of a better word, wily.

In a positive light wily is a synonym for smart.

But, in a darker view wily could mean dishonest.

As you will learn in the conclusion, I believe he was honest,

only because I could not find any credible evidence of the opposite.

However, keep in mind that absence of evidence is not evidence of

absence.

To say that Ben was

outspoken is the height of understatement.

His opponents said he was rude, crude, and a bore to boot.

As a lawyer, being disrespectful of a judge in his own courtroom

is not a recipe for success at the bar.

One of Butler’s cases in the Lowell Police Court, our boy was

fighting for reform of that court.

He had a dislike for Justice Nathan Crosby, the presiding officer

of that court. Crosby jailed

Butler for contempt of court in “threatening violence to the person of

said Justice by using menacing gestures and insulting attitudes toward

said Justice in his presence and view.”

After cooling his heals in jail for a week, Ben appeared before

Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw under a writ of habeas corpus.

Where upon he pleaded “if, in the heat of defending his client,

he had used any improper expression, he regretted it.”

The pugnacious

Benjamin Butler was a fighter, both literally and figurately, all his

life. As mentioned earlier,

he picked fights with his classmates at school and got tossed out of

school because of same. As a

young lawyer he fought professionally at the bar and jousted with fellow

barristers and judges alike.

He fought for causes all his life, some popular and some not so much.

In the army, where he was being paid to fight, he waged war on

the front, in the rear area, and with anyone with whom he saw as the

enemy. It did not matter

whether they wore blue, gray, or civilian clothes.

Why Butler, who was

extremely intelligent and hardworking, chose to pick fights is an open

question. It is hard to do a

psychoanalysis from the 21st century looking back

to a person from the 19th.

Even if I were schooled in psychology, which I am not, this is an

impossible task. I have seen

nothing in my study of him that really tries to explain this.

Often his friends urged him to tone it back in public.

In private Butler acknowledged the justice of this criticism, but

in the heat of debate he usually forgot moderation.

If he was truly an outstanding politician, in the professional

sense of the word, he would have moderated his behavior.

After all, both he and supporters, wanted him to run for

President.

As to the causes he

supported, let’s look at three.

First, as a pre-war Democrat, it is not surprising that he was in

favor of soft money.

However, when he became a Republican during the war, he still favored

easy credit and fought the gold standard.

As a newly elected congressman, he threw in his lot with the

advocates of greenback paper money.

This was cheap money for the masses, easy credit for the farmers,

and an abomination to the bankers.

For this stand, and for other things, Benjamin Butler was never

popular with establishment Republicans.

Second, his support

for the recently liberated slaves grew out of Butler’s long history of

support for the working poor and his more recent war experience with

“contraband.” He, himself,

selected civil rights as the cornerstone of his congressional career.

In fact, the term civil rights gained its modern meaning in the

Civil Rights Act of 1871.

Butler wrote the first draft of this bill which did not pass.

A second version of it, only slightly less sweeping, did pass

Congress and was signed by President Grant.

And

finally, Butler had led the fight against the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1870 he instigated an investigation into the organization.

In the next year, a state Grand Jury reported that: "There has

existed since 1868, in many counties of the state, an organization known

as the Ku Klux Klan, or Invisible Empire of the South, which embraces in

its membership a large proportion of the white population of every

profession and class. The

Klan has a constitution and bylaws, which provides, among other things,

that each member shall furnish him-self with a pistol, a Ku Klux gown,

and a signal instrument. The

operations of the Klan are executed in the night and are invariably

directed against members of the Republican Party.

The Klan is inflicting summary vengeance on the colored citizens

of these citizens by breaking into their houses at the dead of night,

dragging them from their beds, torturing them in the most inhuman

manner, and in many instances murdering." And

finally, Butler had led the fight against the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1870 he instigated an investigation into the organization.

In the next year, a state Grand Jury reported that: "There has

existed since 1868, in many counties of the state, an organization known

as the Ku Klux Klan, or Invisible Empire of the South, which embraces in

its membership a large proportion of the white population of every

profession and class. The

Klan has a constitution and bylaws, which provides, among other things,

that each member shall furnish him-self with a pistol, a Ku Klux gown,

and a signal instrument. The

operations of the Klan are executed in the night and are invariably

directed against members of the Republican Party.

The Klan is inflicting summary vengeance on the colored citizens

of these citizens by breaking into their houses at the dead of night,

dragging them from their beds, torturing them in the most inhuman

manner, and in many instances murdering."

Butler came into

possession of a blood-stained shirt from a victim, who was a white

veteran of the war, of a Klan lashing.

Before the House, Congressman Butler brandished this item as if

it had been evidence in a trail.

He shook the bloody shirt before his fellow congressmen.

And thus, the expression “waving the bloody shirt” entered into

the political language.

You can probably

guess what my conclusion will be.

As you have undoubtably noted, this has not been a regurgitated

the false claims of the lost cause bunch.

I do think that Benjamin F. Butler got a raw deal in his day, in

the intervening years, and even today.

He was no saint, but who during the 19th century was?

With our advantage of hindsight, one can see, as presented, many

of the things we see as modern thought that can trace their roots back

to Ben. If you can look past

his style, we should give him more credit than most historians do.

Here was a Democrat

who fought for the Republicans and actually got many of them won over to

his brand of liberal social issues.

Limited worker hours is just the most obvious gift of his battles

with the establishment. Ben

worked hard for his beliefs and accomplished more in a day than most

people do in a week. In

addition, while being clever he was honest.

In his first encounter in Baltimore he succeeded by taking action

when preparation met opportunity.

From early in the

Civil War to the end of his life he defended, utilized, and promoted the

wellbeing of the black citizens of the United States.

Except for Lincoln’s pen, this man’s action did more for civil

rights than any leader of his day.

He is the classic case of a leader who “put his money where his

mouth was.” Evidence for

this goes back to his mill ownership days, extends forward to his

actions in New Orleans, and continued on for the rest of his life.

He fought for the things that we think are worth fighting for,

such as opposing the Klan.

of the black citizens of the United States.

Except for Lincoln’s pen, this man’s action did more for civil

rights than any leader of his day.

He is the classic case of a leader who “put his money where his

mouth was.” Evidence for

this goes back to his mill ownership days, extends forward to his

actions in New Orleans, and continued on for the rest of his life.

He fought for the things that we think are worth fighting for,

such as opposing the Klan.

In summing up Butler,

it is useful to reflect on what Grant, no help to Ben during the war,

said about him on his world tour after war.

“I had always found General Butler a likeable, able, and

patriotic man of courage, honor, and sincere conviction.

He was, never the less, a man it is the fashion to abuse.”

Last changed: 12/03/19 |