Volume 28, No. 11

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

November 11, 2015 Meeting

Dr. Ralph Levey will speak on “1860: The Year of the Party of

No Compromise, or How to Lose an Election.”

October 11, 2015 Meeting

Robert Krasner, “The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

and His Trip Around the World After Leaving Office”

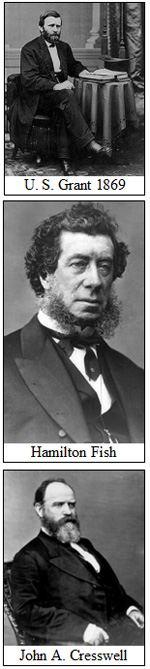

Tuesday, November 3, 1869: Ulysses S. Grant was

elected as our 18th President by an electoral margin of 214 to 80 and

carried 26 of the 34 states then in the Union. At the age of 46, he was

the youngest President up to that date.

Socioeconomic changes: Robert outlined events that

would have an enormous socioeconomic impact on Grant’s Presidency.

First, in 1859, in Oil Creek Valley near Titusville, Pennsylvania,

38-year old Edwin Drake drilled the first successful oil well. During

the Civil War, kerosene refined from crude oil lit lamps by which Grant

could read and draft military dispatches at night. After the Civil

War, oil, not cotton, became King in the world of commerce.

Second, the war brought on an unprecedented economic and technological

boom to the North, in large part due to the existence of a legal system

protective of private property and contracts. It was possible to

obtain corporate charters and bank credit and when an enterprise failed,

to obtain protection from creditors via bankruptcy. Third, the Puritan

ethic and the moral authority of Church and State fell victim to a

“Gilded Age” in which people took unethical shortcuts to obtain great

wealth and influence. Before the war, you could say that politics

was about ideas; after the war, it was about money.

Grant

is inaugurated: March 4, 1867, Grant and his Vice

President, Schuyler Colfax (who served only one term), are sworn in by

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. Grant himself wrote his Inaugural

Address, at least half of which was devoted to fiscal issues: prompt

payment of the National debt, faithful collection of revenue, and

retrenchment in government expenditures. Sound familiar? He

said he would approach Reconstruction “calmly, without prejudice, hate

or sectional pride.” In foreign affairs, Grant promised to protect

all U. S. citizens while abroad and to deal with all nations on the

basis of “fairness and equality.” Then Grant, in the face of a

hostile public mood, promised to assist the integration of native

peoples and former slaves into American society and to support their

ultimate full citizenship by ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to

the U. S. Constitution. Grant

is inaugurated: March 4, 1867, Grant and his Vice

President, Schuyler Colfax (who served only one term), are sworn in by

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. Grant himself wrote his Inaugural

Address, at least half of which was devoted to fiscal issues: prompt

payment of the National debt, faithful collection of revenue, and

retrenchment in government expenditures. Sound familiar? He

said he would approach Reconstruction “calmly, without prejudice, hate

or sectional pride.” In foreign affairs, Grant promised to protect

all U. S. citizens while abroad and to deal with all nations on the

basis of “fairness and equality.” Then Grant, in the face of a

hostile public mood, promised to assist the integration of native

peoples and former slaves into American society and to support their

ultimate full citizenship by ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to

the U. S. Constitution.

Grant forms his cabinet: Grant’s Cabinet, unlike

Lincoln’s, was not a “Team of Rivals.” In fact, Grant did not consult with the

Republican leaders about his choices, which often were not fully

qualified. In all Grant appointed 25 men to cabinet positions.

Some turned out to be corrupt, two died in office and most turned out to

be mediocre at best. Five of his nominees, however, were

exceptional in their service, most notably Secretary of State Hamilton

Fish (1869-77), Postmaster General, John Creswell (1869-74), Secretary

of the Treasury George Boutwell (1869-73), his third Secretary of the

Treasury, Benjamin Bristow (1874-76), and his fourth Secretary of War

(3/8/1876-5/22/1876) and fifth Attorney General, Alphonso Taft

(5/22/1876-3/4/1877).

“Team of Rivals.” In fact, Grant did not consult with the

Republican leaders about his choices, which often were not fully

qualified. In all Grant appointed 25 men to cabinet positions.

Some turned out to be corrupt, two died in office and most turned out to

be mediocre at best. Five of his nominees, however, were

exceptional in their service, most notably Secretary of State Hamilton

Fish (1869-77), Postmaster General, John Creswell (1869-74), Secretary

of the Treasury George Boutwell (1869-73), his third Secretary of the

Treasury, Benjamin Bristow (1874-76), and his fourth Secretary of War

(3/8/1876-5/22/1876) and fifth Attorney General, Alphonso Taft

(5/22/1876-3/4/1877).

Fish, a personal friend of Julia Grant and a former New York Governor

and Senator, developed the concept of international arbitration to

settle the controversial Alabama claims, avoided war with Spain over

Cuba, started the process toward Hawaiian statehood, brokered a peace

conference between Spain and its former South American colonies, and

settled the Liberian-Grebo war. Grant said Fish was the person he

most trusted for political advice. [Note: Actually, Fish was

Grant’s second Secretary of State because he had appointed Elihu

Benjamin Washburne to that post on March 5, 1869. Grant's

appointment was intended as a personal yet temporary means of honoring

Washburne, who held office until relieved by Fish, on March 16, 1869.]

Creswell, a Maryland Democrat turned Radical Republican and a former U.

S. Representative and Senator, improved the postal system and became one

of the most effective Postmaster Generals in U. S. history.

Boutwell, former Governor of Massachusetts, was the architect of the

13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to our Constitution and author of needed

reforms in the Treasury Department. Taft put soldiers in charge of

Indian trading posts, reducing corruption.

The rest of the initial Cabinet consisted of Secretary of the Navy

Adolph Borie (1869), a wealthy retired Philadelphia merchant who had

prospered in the East Indian Trade and founded the Union League Club of

Philadelphia; [Note: Borie was totally unsuited for the position

and after only 4 1/2 months he returned to his business life. He

remained a friend of Grant’s and accompanied Grant on his trip around

the world.] Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox (1869-70), former

Governor of Indiana and professor of law at the University of

Cincinatti, had been a reasonably competent general in the Civil War,

and was an enthusiastic reformer who was forced out in November 1870

because Grant did not back him against the spoils system; Attorney

General Ebenezer Hoar (1869-70) of Massachusetts, former Associate

Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court and a member of the Harvard

College Board of Overseers was asked to resign in June 1870, ostensibly

because of the tradition that no cabinet member could be from the same

state as another; [Note: Your editor could not resist this

footnote: When Harvard College instituted the “House” student residence

system, Mr. Hoar’s name was rejected as a name for one of the Houses,

because as a faculty member famously noted, “We don’t want a Hoar

house at Harvard.”] and last, but not least, Secretary of War John

Rawlins (1869), Grant’s wartime adjutant, chief advisor and close friend

from Galena, Illinois, who died of tuberculosis after only seven months

in office.

Buying war bonds back with gold: The national

debt, $64 million in 1860, had grown to $2.8 billion in 1869, most in

the form of 6% bonds. There was $356 million in “greenbacks” in

circulation, backed only by the “full faith and credit” of the U. S.,

which had driven gold coinage out of circulation. Finally there

was $160 million in “fractional” paper currency, which had driven silver

coinage out of circulation. On March 18,1869, Grant signed his

first law: “An Act to Strengthen the Public Credit,” which pledged

to pay all bondholders in gold at par and to redeem all paper money as

soon as practicable. Until the Civil War, there had been no

government-issued paper money. There were only gold coins and

gold-backed certificates. There was about $100 million in gold in the

entire U. S., of which $20 million was in circulation and $80 million

held by the government. To strengthen the dollar, Treasury

Secretary Boutwell, backed by Grant, sold gold from the Treasury each

month and bought back high-interest Treasury bonds issued during the

war. This reduced the deficit but deflated the currency.

“Black

Friday,” September 24, 1869: Grant breaks the Gold Ring’s

effort to corner the gold market: Wall Street speculator, Jay

Gould, and railroad magnate, Jim Fisk, tried to corner the gold market

by bribing Grant’s brother-in-law Abel Corbin to influence Grant to

appoint Gould’s associate, Daniel Butterfield as Assistant Treasurer.

The “Gold Ring” also bribed Grant’s personal secretary, Horace Porter

for advance information of the amount of gold to be sold by the

government. At the start of 1869, gold cost $131 per ounce. By September

21, the Gold Ring owned $50 to $60 million in gold acquired at an

average cost of $141 per ounce. The price of gold rose to a peak of $162

an ounce. Grant became aware of the unnatural increase in the

price of gold and felt that the country was in danger. He took

command and promptly ordered Boutwell to avoid a panic by selling $4

million in gold on September 4, 1977. T his reduced the price of gold

overnight to $133 per ounce, breaking the Gold Ring. This was a

watershed in the history of the American economy: For the first

time in its history, the federal government had intervened massively to

bring order to the marketplace. “Black

Friday,” September 24, 1869: Grant breaks the Gold Ring’s

effort to corner the gold market: Wall Street speculator, Jay

Gould, and railroad magnate, Jim Fisk, tried to corner the gold market

by bribing Grant’s brother-in-law Abel Corbin to influence Grant to

appoint Gould’s associate, Daniel Butterfield as Assistant Treasurer.

The “Gold Ring” also bribed Grant’s personal secretary, Horace Porter

for advance information of the amount of gold to be sold by the

government. At the start of 1869, gold cost $131 per ounce. By September

21, the Gold Ring owned $50 to $60 million in gold acquired at an

average cost of $141 per ounce. The price of gold rose to a peak of $162

an ounce. Grant became aware of the unnatural increase in the

price of gold and felt that the country was in danger. He took

command and promptly ordered Boutwell to avoid a panic by selling $4

million in gold on September 4, 1977. T his reduced the price of gold

overnight to $133 per ounce, breaking the Gold Ring. This was a

watershed in the history of the American economy: For the first

time in its history, the federal government had intervened massively to

bring order to the marketplace.

Foreign Policy: Three countries play a noticeable

role in Grant’s foreign policy: Spain, the Dominican Republic and

England.

Grant won’t intervene in Cuban Revolt: In 1869,

Spain was putting down an insurrection by Cuban rebels, who were

supported by various groups in the U. S. who wanted to arm the rebels,

overthrow the Spanish colonial government and even annex Cuba.

Spain responded by intercepting and searching all American ships bound

for Cuba. Grant put an end to the war talk by stating that the U.

S. could not recognize the insurgents because they held no town, no

established seat of government and no organization for collecting

revenue.

Failed effort to annex the Dominican Republic:

Grant had been initially skeptical about annexing the Dominican

Republic, but at the urging of Admiral Porter, who wanted a naval base

at Samaná Bay, and Joseph W. Fabens, a New England businessman employed

by the Dominican government, Grant became convinced of the plan's merit.

He sent Orville Babcock, a wartime confidant, to consult with

Buenaventura Báez, the Dominican president, who supported annexation.

Babcock returned with a draft treaty for annexation in December 1869.

Secretary of State Fish dismissed the idea, seeing the island as

politically unstable, but out of loyalty joined Grant’s unsuccessful

effort to win Congressional approval. Congress voted this

initiative down for three reasons: (1) Grant had acted without prior

Senate approval; (2) Acquiring the Dominican Republic would threaten the

independence of Haiti, the only independent Black republic in the

Western Hemisphere; and (3) Real estate speculation was occurring among

American investors, local politicians and even some of Grant’s aides,

which would seriously embarrass the United States.

The “Alabama Claims:” CSS Alabama had

been built in a British shipyard in 1862. During the next two

years it circumnavigated the globe sinking more than 60 Union ships

until it was finally sunk off Cherbourg, France by USS Kearsage.

By the time Grant takes office, Great Britain is being pressed to make

good the losses caused by CSS Alabama and other Confederate

raiders. Private damage claims had been settled by insurance.

Initially, Great Britain offered to pay $20 million for “actual losses”

to American public property, but refused to reimburse indirect or

consequential losses due to selling arms to the South. Thus the

issue was: Direct Losses vs. Indirect Losses. Charles Sumner (Mass.),

Chairman of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, had three goals: Make

Great Britain (1) pay for the merchant fleet losses totaling $110

million; (2) admit that its involvement prolonged the war; and (3) admit

that its involvement caused the U. S. debt to spiral to $2.5 billion.

The first use of international arbitration to settle claims:

The obstacles in the way of collecting these claims include: (1) the

American Navy was largely demobilized following the end of the war; (2)

The British Navy, based on steel-clad vessels driven by steam far

outclassed the American Navy; (3) U. S. Government bonds were nosediving

in value; (4) American industry was largely financed by British money;

(5) Where would American business go if British banks stopped lending

money, since American banks had almost nothing left to lend?; (6) War

with Great Britain would exacerbate the U. S. debt; and lastly,

threatening war with Great Britain made U. S. financial leaders nervous.

Grant’s solution, due largely to his Secretary of State, is the Treaty

of Washington, which commits both sides to arbitration. One U. S.

diplomat and one English diplomat would agree on a panel of arbitrators

who would recommend a “declaration” (not a “decision”) on the issue of

indirect claims. The panel promptly declares it has no power to

consider indirect claims. The result was the award of $15.5 million and

the establishment of what is still one of the most important precedents

in International Law: settling disputes between great nations by

international arbitration rather than the threat or use of force.

Domestic Policy – Reforming Native American policies:

Grant respected Native Americans and was aware that greed, corruption, brutality and the saying that “the

only good Indian was a dead Indian” infected policy. Grant was

determined to develop programs aimed at full citizenship and

accommodation rather than genocide. To this end, Grant relied on

Secretary of Interior Jacob Cox and Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ely

S. Parker (the first Native American appointed to that post), to carry

out his policy. Parker, (born Hasanoanda and later known as

Donehogawa) was a Seneca attorney, engineer, and tribal diplomat.

During the war, he had served as adjutant to Grant, written down the

official copy of the Confederate surrender terms at Appomattox, rose to

the rank of Brevet Brigadier General, one of only two Native Americans

to earn a general's rank during the war (the other being Stand Watie,

who fought for the Confederacy) and was Grant’s “eyes and ears” to keep

tabs on frontier conditions after the war.

and was aware that greed, corruption, brutality and the saying that “the

only good Indian was a dead Indian” infected policy. Grant was

determined to develop programs aimed at full citizenship and

accommodation rather than genocide. To this end, Grant relied on

Secretary of Interior Jacob Cox and Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ely

S. Parker (the first Native American appointed to that post), to carry

out his policy. Parker, (born Hasanoanda and later known as

Donehogawa) was a Seneca attorney, engineer, and tribal diplomat.

During the war, he had served as adjutant to Grant, written down the

official copy of the Confederate surrender terms at Appomattox, rose to

the rank of Brevet Brigadier General, one of only two Native Americans

to earn a general's rank during the war (the other being Stand Watie,

who fought for the Confederacy) and was Grant’s “eyes and ears” to keep

tabs on frontier conditions after the war.

A major task for Grant’s policy was to get Congress to approve a $4

million appropriation to fund administration of Indian affairs.

Due to graft and bureaucratic overhead, only 25% of the money

appropriated ever reached the tribes. Grant adopted the

recommendation of a group of philanthropists to appoint a commission to

supervise the spending of Federal funds. Grant never wavered in

his efforts to reform the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Blocked by

Congressional inaction, he issued an Executive Order authorizing the

Commissioner of Indian Affairs to inspect and report on all aspects of

Indian policy. Despite setbacks and public criticism, Grant

persevered, believing deeply in human equality for both Native Americans

and former slaves and changed the way Americans thought about Native

Americans and helped save them from extinction.

Reconstruction:

By the time Grant moved into the White House, Reconstruction had failed,

but Grant thought that there was still a chance to make it work.

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified July 9, 1868, granted citizenship to

“all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” which included

former slaves recently freed. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified

February 3, 1870, declared that the “right of citizens of the United

States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or

by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of

servitude.” Ratification was celebrated by a 100-gun salute and a

torchlight parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. Speaking from the

front steps of the White House, Grant said the new right would be used

wisely and that the Fifteenth Amendment was the most important event in

the nation’s history. To protect the rights of the freedmen, Grant

appointed a new Attorney General, Amos Ackerman (1821-80) [Note:

Ackerman, born in New Hampshire, had moved south and served in the

Confederate army and therefore was Grant’s first Southern appointment.

Although he served only 18 months, he took office as head of the newly

formed Justice Department, which had been created to handle all of the

federal government's litigation (previously, each department hired its

own lawyers on a case-by-case basis), and he began the department's

first investigative unit, which later became the Federal Bureau of

Investigation. His term ended when he was asked to resign because

of his opposition to land grants to railroad speculators, squeaky clean

interpretation of the new Civil Service Act and his energetic anti-Klan

efforts.] and Congress passed three Enforcement Acts making it a

Federal offense to attempt to deprive someone of his political rights.

[Note: The Supreme Court later struck down these Acts as invasive

of states’ rights in U. S. v. Cruikshank, 92 US 542 (1875), holding that

the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment applied only to state action, not to actions by individual

citizens. It said that the plaintiffs had to rely on state courts for

protection.] Congress also passed a law establishing a permanent

U. S. Department of Justice (authorizing the Attorney General to

supervise the U.S. attorneys and Federal Marshals) and the Office of the

Solicitor General, naming Benjamin Bristow as the first Solicitor

General. Reconstruction:

By the time Grant moved into the White House, Reconstruction had failed,

but Grant thought that there was still a chance to make it work.

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified July 9, 1868, granted citizenship to

“all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” which included

former slaves recently freed. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified

February 3, 1870, declared that the “right of citizens of the United

States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or

by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of

servitude.” Ratification was celebrated by a 100-gun salute and a

torchlight parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. Speaking from the

front steps of the White House, Grant said the new right would be used

wisely and that the Fifteenth Amendment was the most important event in

the nation’s history. To protect the rights of the freedmen, Grant

appointed a new Attorney General, Amos Ackerman (1821-80) [Note:

Ackerman, born in New Hampshire, had moved south and served in the

Confederate army and therefore was Grant’s first Southern appointment.

Although he served only 18 months, he took office as head of the newly

formed Justice Department, which had been created to handle all of the

federal government's litigation (previously, each department hired its

own lawyers on a case-by-case basis), and he began the department's

first investigative unit, which later became the Federal Bureau of

Investigation. His term ended when he was asked to resign because

of his opposition to land grants to railroad speculators, squeaky clean

interpretation of the new Civil Service Act and his energetic anti-Klan

efforts.] and Congress passed three Enforcement Acts making it a

Federal offense to attempt to deprive someone of his political rights.

[Note: The Supreme Court later struck down these Acts as invasive

of states’ rights in U. S. v. Cruikshank, 92 US 542 (1875), holding that

the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment applied only to state action, not to actions by individual

citizens. It said that the plaintiffs had to rely on state courts for

protection.] Congress also passed a law establishing a permanent

U. S. Department of Justice (authorizing the Attorney General to

supervise the U.S. attorneys and Federal Marshals) and the Office of the

Solicitor General, naming Benjamin Bristow as the first Solicitor

General.

When the 42nd Congress convened on March 4, 1871, the South boiled with

violence, much directed at former Union soldiers. At Grant’s

request, on April 20, 1871, Congress passed the “Klu Klux Klan Act,”

making it a federal offense to conspire to prevent persons from holding

office, voting or enjoying the equal protection of law, suspending the

write of habeas corpus and empowering the President to use the army to

enforce the law. This law represented an enormous peacetime

extension of federal authority–for the first time, private acts of

violence became federal crimes. Grant urged voluntary compliance

and asked the South to help suppress the Klan. Federal grand

juries returned over 3,000 indictments in 1871 alone, and, with the

assistance of former Klan members, 600 were convicted. Most paid

fines or got short jail sentences. Sixty-five defendants received

five year sentences. By 1872, Grant’s determined use of full legal

and military measures had broken the Klan. By then, however, most

Northerners were losing interest in Reconstruction. Proof of this

changing opinion was enactment of the “Amnesty Act of 1872,” which

allowed all but 500 former Confederates to vote again. The effects

of the Amnesty Acts were almost immediate. By 1876, Democrats had

regained control of all but three states in the South. Black Republicans

clung to power in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida, but only with

the help of federal troops.

Grant’s Second Term

Panic of 1873: Grant was re-elected with 56%

of the popular vote and the Republicans retained control of both houses.

On September 17, 1873, as Grant supped with Jay Cooke (the banker who

had helped Lincoln finance the Civil War) the Northern Pacific Railroad

ran out of money. The result was the Panic of 1873 – businesses

failed, people lost their jobs and many farmers failed. Congress

reacted in April 1874 by passing the “Inflation Bill,” legalizing the

reissue of $26 million in greenbacks and authorizing the Treasury to

issue $18 million new greenbacks, bringing total circulation to $400

million. Grant vetoed the bill because (1) it would wreck the

credit of the American government; (2) inflation would shoot into double

figures; (3) recession would become depression; and (4)

industrialization would stop. Grant felt he was using moral

courage by doing the hard thing that was right rather than the easy

thing that was wrong.

On January 14, 1875, Grant signed the “Resumption Act,” restoring specie

payment and discontinuing printing greenbacks which had deflated the

dollar. The adoption of a stable currency began the first steps

toward recovery. [Note: In 1874, there was no mechanism to apply the

brakes when the economy was overheating.] Without a standard of

value (gold), Congress was free to expand the money supply unchecked.

Republicans lose the House in 1874: Congress will

spend the rest of Grant’s second term embroiled in Reconstruction

controversies.

“Whiskey Ring” fraudulently lowers its taxes by bribing the internal

revenue superintendent: Grant’s new Treasury Secretary, Benjamin

Bristow, working without the knowledge of the President or the Attorney

General, broke the tightly connected and politically powerful ring in

1875 using secret agents from outside the Treasury department to conduct

a series of raids across the country on May 10, 1875. U ltimately, over

350 individuals were indicted, of whom 110 were convicted and over $3

million in taxes was recovered.

Custer and the Battle of Little Big Horn: Although the

Sioux gained nothing from this victory, it dealt a serious blow to

Grant’s popularity and Grant’s peace policy was faltering. However, no

president could have done more and none had done as much.

July 4, 1876 and the Election of 1876: The

Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania marks the 100th

anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. That fall, the election

depended upon the votes in three states: Florida, Louisiana and South

Carolina. Grant steps in to appoint a special arbitration

commission, which votes 8 -7 on party lines for Rutherford B. Hayes.

The price would be the withdrawal of Federal troops from the Southern

states, ensuring 100 years of Jim Crow, lynching, and white control.

Grant’s Trip Around the World, May 17, 1877 - September 20,

1879: When Ulysses S. Grant left the White House in 1877,

he certainly needed a vacation. His reputation had been severely

damaged by corruption in his administration and his party. And the

difficulties of trying to reunite North and South proved tiring and

unrewarding. But when Grant left with his family for England on

May 17, 1877 for a world tour, he had more than rest and relaxation in

mind. Grant hoped that if people in other countries showed their

admiration for him, Americans would forget the scandals of his

presidency. If they did, he might win the Republican nomination -

and recapture the presidency - in 1880. But even if Grant expected

that foreigners would treat him with honor, the reception he received

probably surprised him.

The Grants' ship arrived in Liverpool, England on May 28, 1877.

Huge crowds turned out to welcome Grant, who was honored not as a former

president, but as the military hero who saved America from falling

apart. British leaders, from the Prince of Wales to Queen Victoria

herself, lined up to host the Grants at lavish dinners and receptions.

The Queen was irritated because the Grants brought their son Jesse along

to meet her. Still, she treated them cordially, although she later

referred to 19 - year - old Jesse as a “very ill-mannered young Yankee.”

All across Western Europe, from Belgium to Switzerland and Germany, the

Grants were treated like royalty. Perhaps the most incredible

display of affection came in Newcastle, England, which the Grants

visited on September 22, 1877. An estimated 100,000 people, most

of them factory workers, turned out to honor Grant with a parade and

hear him speak.

If Grant’s tour was successful in Europe, it was also doing its job in

the U.S. Reporter John Russell Young from the New York Herald traveled

with the Grants, and sent dispatches home to eager readers in New York.

Other papers picked up the reports. All over America, people began

to forget Grant's scandals and remember his heroism. An example is

the following portion of a conversation between Grant and Otto von

Bismark, “The Iron Chancellor of Germany:” Bismark, “What always

seemed so sad to me about your last great war was that you were fighting

your own people. That is always so terrible in wars, so very

hard.” Grant,“But it had to be done.” Bismark, “Yes, you had to

save the Union just as we had to save Germany.” Grant, “Not only

save the Union, but destroy slavery.” Bismark,“I suppose, however,

the Union was the real sentiment, the dominant sentiment.” Grant,

“In the beginning, yes, but as soon as slavery fired on the flag it was

felt, we all felt, even those who did not object to slavery, that

slavery must be destroyed. We felt that it was a stain on the

Union that men should be bought and sold like cattle.”

The Grants kept moving. In Egypt, they visited Alexandria and

Cairo, and steamed up the Nile.

They toured Jerusalem and saw the Western world's holiest sites.

Then they moved on, to Greece and Rome, Russia, Austria, and Germany.

After briefly returning to Britain, the Grants set out for Asia.

They toured Burma, Singapore, and Vietnam. In Siam, the Grants met King

Chulalongkorn, who at 25 had already been king for 10 years. In

China, Grant declined to ask for an interview with the Guangxu Emperor,

a child of seven, but did speak with the head of government, Prince

Gong, and Li Hongzhang, a leading general. They discussed China's

dispute with Japan over the Ryukyu Islands, and Grant agreed to help

bring the two sides to agreement. After crossing over to Japan and

meeting Emperor Mutsuhito and Empress Haruko (Grant was said to be the

first person in the world to shake the Emperor's hand), Grant convinced

China to accept the Japanese annexation of the islands, and the two

nations avoided war.

They toured Jerusalem and saw the Western world's holiest sites.

Then they moved on, to Greece and Rome, Russia, Austria, and Germany.

After briefly returning to Britain, the Grants set out for Asia.

They toured Burma, Singapore, and Vietnam. In Siam, the Grants met King

Chulalongkorn, who at 25 had already been king for 10 years. In

China, Grant declined to ask for an interview with the Guangxu Emperor,

a child of seven, but did speak with the head of government, Prince

Gong, and Li Hongzhang, a leading general. They discussed China's

dispute with Japan over the Ryukyu Islands, and Grant agreed to help

bring the two sides to agreement. After crossing over to Japan and

meeting Emperor Mutsuhito and Empress Haruko (Grant was said to be the

first person in the world to shake the Emperor's hand), Grant convinced

China to accept the Japanese annexation of the islands, and the two

nations avoided war.

Americans must have read of Grant’s adventures with fascination.

At the time, Asia was largely unfamiliar territory to most Americans -

Grant included. America did not yet enjoy close political

relations with many Asian nations. By the time the Grants returned

to America, on December 16, 1879, the former president's image had

improved. When he disembarked at San Francisco, with the St.

Bernard, named Ponto, he’d acquired in Switzerland, he was met by an

enormous crowd. But as Grant continued his tour through the cities

and towns of America, support for him diminished. The world tour

had been thrilling, but it would not be enough to help Grant regain the

presidency. When the ballots were counted at the Republican

convention of 1880, James A. Garfield was the winner of the party's

nomination.

Grant’s Historical Reputation has Risen, Fallen and Risen:

Throughout the 20th century, historians ranked his presidency near the

bottom. In the 21st century, his military reputation is strong,

while experts rank his presidential achievements well below average.

The same qualities that made Grant a success as a general carried over

to his political life to make him, if not a successful president, then

certainly an admirable one. The common thread is strength of

character—an indomitable will that never flagged in the face of

adversity. As commanding general in the Civil War, he had defeated

secession and destroyed slavery, secession's cause. As President

during Reconstruction he had guided the South back into the Union.

By the end of his public life the Union was more secure than at any

previous time in the history of the nation. And no one had done

more to produce the result than he.

Robert received a well-earned round of applause, followed by a Q-and-A

session.

Note: Don’t miss “By Land and Sea: Florida in the American Civil War” at

the Palm Beach County History Museum, 300 North Dixie Highway, West Palm

Beach (it runs through July 2, 2016).

Last changed: 11/06/15

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|