Volume

27, No. 12 – December 2014

Volume 27, No. 12

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

The President’s Message

After a long day’s marching, join the troops on

Wednesday, December 10, 2014 at 7:00 PM and enjoy the Round Table’s

annual holiday festivities. Everyone is asked to go to their local

sutler and bring an appetizer, salad, entrée

or dessert. Bring yourself and any sweethearts that you may find along

the way. Speaking around the campfire will be noted author, Robert

Macomber. Every soldier needs a holiday treasure to bid on so please

bring something for the raffle. Items do not have to be Civil War

related. Gift cards would be greatly appreciated.

Besides delicious rations and camaraderie at the holiday party you

can also get your horse shod, have long johns repaired, get coffee beans

ground, have socks washed, get sideburns trimmed, have bullets polished,

have melancholia vanished, get your saber sharpened, and dyspepsia

diagnosed and treated.

Dues are due. Elections will be held in January. If you wish to

run for any office or be on the Board, please call (561 967-8911) or

e-mail (honeybell7@aol.com).

Gerridine LaRovere

December 10, 2014 Program:

Robert Macomber, The American Civil War Around the World

Join award-winning author and lecturer Robert N. Macomber for an

intriguing discussion of the global aspects of the American Civil

War. That's right, the naval part of the Civil War was fought around the

world and had interesting consequences. This aspect of history is little

known. For more about Mr. Macomber and his work, visit

http://www.robertmacomber.com.

November 12, 2014 Program – Naval Terrorism in the

Civil War:

Infernal Machines and Countermeasures.

Dr. Francis J. DuCoin, a consultant at the USS Monitor Center

in Newport News, Virginia, is an avid Civil War collector and historian.

His second appearance at the Round Table was both interesting and

depressing. First the interesting:

As part of "asymmetric warfare," the Confederates engaged in the kind

of guerrilla warfare Americans have learned to hate in Vietnam, Iraq and

Afghanistan. Civil War buffs are familiar with land-based guerrilla

warfare. Examples include: On August 9, 1864, an infernal machine (we

call them bombs today) in the form of a "horological torpedo," (i.e. a

time bomb) invented by CSA John Maxwell was smuggled aboard an

ammunition barge which blew up a naval ship and caused tremendous death

and damage to the naval yard at City Point, Virginia. On October 19,

1864, a Confederate raiding party took over St. Albans, Vermont, robbing

the banks and merchants of $208,000 ($3.14 million today) and attempted

to burn the town down but the "Greek Fire" failed to ignite and only one

shed was destroyed. In November 1864, a group of Confederate

sympathizers attempted to burn New York City down.

But

we are not so familiar with naval asymmetric warfare, which began on

July 7, 1861, when a Confederate force floated two barrels down the

Potomac River in an abortive attempt to sink USS Powhatan.

Curious Federal soldiers dragged them out of the water and were aghast

to discover each barrel had been packed with 200 pounds of explosives

and a 40-foot fuse, which fortunately had gone out. But

we are not so familiar with naval asymmetric warfare, which began on

July 7, 1861, when a Confederate force floated two barrels down the

Potomac River in an abortive attempt to sink USS Powhatan.

Curious Federal soldiers dragged them out of the water and were aghast

to discover each barrel had been packed with 200 pounds of explosives

and a 40-foot fuse, which fortunately had gone out.

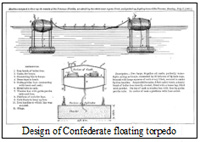

The

Confederate Congress in October 1862 set up two agencies: the Torpedo

Bureau, to develop "torpedoes" (the word was coined by Robert Fulton;

today we call them "mines" and Dr. DuCoin referred to them as mines in

his talk) and the Submarine Battery Service to develop submarines to

deliver them to the hulls of Northern vessels, with modest success:

During the Civil War, the South planted 123 mines in Charleston Harbor,

which helped prevent its capture; 101 mines in the Roanoke River and a

multitude of mines outside Savannah, Georgia. Of 12 vessels sent with

troops to capture Fort Branch, North Carolina, six were sunk by mines.

Of the five ironclads sent to take Mobile, Alabama, three were destroyed

by mines. Altogether 58 Northern vessels were sunk by Confederated

mines, including Admiral Farragut's flagship, USS Harvest Moon,

Thorn, Commodore Jones, Monitors Patapsco (62 sailors

died) and Tecumseh (93 died), and Ram Osage and Monitors

Milwaukee, Housatonic and Cairo in the Yazoo River.

Northern Monitors sat low in the water and had only 1/2 inch iron in

their hulls below water. Once struck by a mine, they often capsized

because of the top heavy weight of the guns. The

Confederate Congress in October 1862 set up two agencies: the Torpedo

Bureau, to develop "torpedoes" (the word was coined by Robert Fulton;

today we call them "mines" and Dr. DuCoin referred to them as mines in

his talk) and the Submarine Battery Service to develop submarines to

deliver them to the hulls of Northern vessels, with modest success:

During the Civil War, the South planted 123 mines in Charleston Harbor,

which helped prevent its capture; 101 mines in the Roanoke River and a

multitude of mines outside Savannah, Georgia. Of 12 vessels sent with

troops to capture Fort Branch, North Carolina, six were sunk by mines.

Of the five ironclads sent to take Mobile, Alabama, three were destroyed

by mines. Altogether 58 Northern vessels were sunk by Confederated

mines, including Admiral Farragut's flagship, USS Harvest Moon,

Thorn, Commodore Jones, Monitors Patapsco (62 sailors

died) and Tecumseh (93 died), and Ram Osage and Monitors

Milwaukee, Housatonic and Cairo in the Yazoo River.

Northern Monitors sat low in the water and had only 1/2 inch iron in

their hulls below water. Once struck by a mine, they often capsized

because of the top heavy weight of the guns.

The US Navy used many countermeasures: Picket boats surrounded the

fleet 24/7 but did not always succeed: On April 9, 1864, the CSS

Squib exploded a mine alongside USS Minnesota, the flagship

of the North Atlantic Blockade Squadron, to the embarrassment of the US

Navy, but failed to sink her. In the campaign to recapture Fort Sumter

in Charleston Harbor, each night a Northern monitor would steam up to

the Confederate barrier and then drift back to the fleet looking for

mines, which at low tide could sometimes be seen just under the water.

USS Sangamon was equipped with "cow catchers" all around her hull

to fend off floating mines. In the "Riverine War" in the West, sailors

would be put ashore to walk along both sides of the a river looking for

underwater cables and wires connected to floating mines.

Hidebound Federal naval officers attacked the use of "torpedoes" as

"unfair" and "unsporting," although the North also used them. On April

3, 1862, one John McCurdy submitted a plan to Secretary of War Stanton

to attach log booms 300 feet long in front of USS Monitor with

mines attached in front of the booms that would explode on contact with

CSS Virginia. This particular plan did not reach the Navy

Department until 1931! Another man requested funds to develop a

submarine "battery" that would sink CSS Virginia ($300,000 in

advance and $100,000 if successful). Many Northern politicians wanted to

capture Charleston desperately – you might say they had a vendetta

against Fort Sumter and Charleston Harbor, symbolic heart of the

Confederacy. These politicians wanted the monitors to beat their way

past the rebel batteries and into the harbor. The US Navy was not

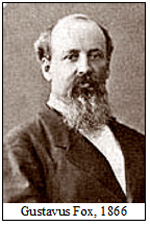

excited about this foolhardy plan. Assistant Secretary

Gustavus

Fox had a special motivation because he had led the failed expedition to

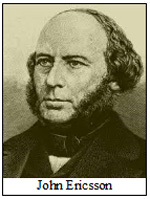

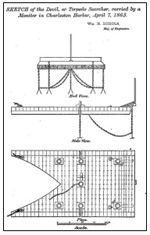

relieve Fort Sumter in 1861. In 1863 he asked John Ericsson, who had

developed USS Monitor (and until recently the only man not a

politician or a military leader to have a statue in Washington, D. C.),

to develop a device to defeat the mines. Ericsson built a 50' x 20' raft

that could be attached to the bow of a monitor, pushed into the desired

site, then lowered under water so it could contact a mine and cause it

to blow up. The US Navy officials in charge of the project thought

Ericsson was "nuts," both because an explosion so close to the monitor

would sink it too and because they didn’t think the monitor could steer

the raft. Ericsson countered the first argument by developing an

explosive that would explode in only one direction, forward. Ericsson

paid $19,000 ($210,000 today) each to build four rafts. He called them

"Devils" or "Torpedo Searchers." The rafts were towed from Hampton Roads

to Charleston Harbor. One raft was lost the first night. Raft #3 was Gustavus

Fox had a special motivation because he had led the failed expedition to

relieve Fort Sumter in 1861. In 1863 he asked John Ericsson, who had

developed USS Monitor (and until recently the only man not a

politician or a military leader to have a statue in Washington, D. C.),

to develop a device to defeat the mines. Ericsson built a 50' x 20' raft

that could be attached to the bow of a monitor, pushed into the desired

site, then lowered under water so it could contact a mine and cause it

to blow up. The US Navy officials in charge of the project thought

Ericsson was "nuts," both because an explosion so close to the monitor

would sink it too and because they didn’t think the monitor could steer

the raft. Ericsson countered the first argument by developing an

explosive that would explode in only one direction, forward. Ericsson

paid $19,000 ($210,000 today) each to build four rafts. He called them

"Devils" or "Torpedo Searchers." The rafts were towed from Hampton Roads

to Charleston Harbor. One raft was lost the first night. Raft #3 was beached and captured by the Confederate Navy. More about raft #3 later.

The other rafts made it. On April 7, 1863, 9 ironclads and 7 monitors

under the reluctant command of Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont (yes

that family!) began an attack on Fort Sumter. DuPont thought only a

combined attack by ground troops and his vessels could succeed (and

subsequent events proved him right).

beached and captured by the Confederate Navy. More about raft #3 later.

The other rafts made it. On April 7, 1863, 9 ironclads and 7 monitors

under the reluctant command of Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont (yes

that family!) began an attack on Fort Sumter. DuPont thought only a

combined attack by ground troops and his vessels could succeed (and

subsequent events proved him right).

The whole thing was a fiasco. First monitor USS Weehawken’s

anchor caught on a grapnel on the raft delaying the attack for two

hours. The whole thing lasted only two hours, during which the

Confederate batteries fired 2,000 rounds of which over 500 hit a Federal

vessel. The US Navy,

on

the other hand, fired only 154 rounds with no apparent effect and

withdrew! Five monitors were badly damaged and USS monitor Keokuk

was sunk. DuPont waited two weeks to report on this "battle" leaving

President Lincoln to find out about it in the Richmond Examiner.

In June DuPont was relieved and never served aboard ship thereafter. on

the other hand, fired only 154 rounds with no apparent effect and

withdrew! Five monitors were badly damaged and USS monitor Keokuk

was sunk. DuPont waited two weeks to report on this "battle" leaving

President Lincoln to find out about it in the Richmond Examiner.

In June DuPont was relieved and never served aboard ship thereafter.

Now for raft #3 after the rebels gave up on trying to salvage it: Dr.

DuCoin and his wife, over a period of several years, took "vacations" in

areas where the raft might have ended up. He discovered it had broken

into six pieces. One piece floated all the way to Bermuda and was

salvaged in 1868; it remains there today. In1872, a steamer ran across

another part of the raft and towed it into a Virginia port. By 2011,

there was very little left of this part of raft #3. In a swampy area of

Virginia, Dr. DuCoin found it. He thinks he was the first person in over

30 years to lay eyes on it. It is slowly disintegrating and he has pictures over several years showing this. He brought several pieces

from raft #3 for us to see up close!

has pictures over several years showing this. He brought several pieces

from raft #3 for us to see up close!

This ends the interesting part of Dr. DuCoin’s talk and he received a

well-deserved round of applause.

Now for his depressing news. Due to budget constraints in 2013, the

Monitor Museum was closed on January 1, 2014. The total cost to operate

the museum is about $750,000 a year, of which the wet lab conservation

work takes $450,00. At this funding rate conservation projects in the

wet labs could have been completed in about 20 years. The National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ("NOAA") got its 2014 funding in

May 2014 and committed $200,000 for the balance of the year. During the

summer and fall, conservators continued to conserve small artifacts, but

had to stop working in the wet lab. The large artifacts (USS

Monitor’s turret, guns, hull, etc.) are covered with tarps and

monitored to maintain their stability. The Museum and NOAA hope to raise

the funds needed to resume conservation work in the wet lab.

[Editor’s note: The following story in The New York Times,

November 25, 2014, is both timely and eerie.]

As Booths Were On stage, Confederate Plot Against New York City

Fizzled

By Sam Roberts

On

Nov. 25, 1864, at some point in the middle of Act II, after Brutus and

his co-conspirators decide to assassinate Julius Caesar, the capacity

crowd of 2,000 filling the Winter Garden on lower Broadway was startled

by the sudden clanging of fire-bells, coming from every direction. After

conferring with the theater manager, Caesar himself, played by Edwin

Thomas Booth, calmly announced from the stage that, indeed, a small fire

had broken out in the adjacent Lafarge House Hotel, but had been

extinguished. The benefit performance, also starring his brothers,

Junius Brutus Booth, Jr., as Cassius, and John Wilkes Booth as Marc

Antony, had been mounted to subsidize a statute of Shakespeare in

Central Park, and resumed without further interruption. This was the

first and last time all three brothers had appeared on stage together. On

Nov. 25, 1864, at some point in the middle of Act II, after Brutus and

his co-conspirators decide to assassinate Julius Caesar, the capacity

crowd of 2,000 filling the Winter Garden on lower Broadway was startled

by the sudden clanging of fire-bells, coming from every direction. After

conferring with the theater manager, Caesar himself, played by Edwin

Thomas Booth, calmly announced from the stage that, indeed, a small fire

had broken out in the adjacent Lafarge House Hotel, but had been

extinguished. The benefit performance, also starring his brothers,

Junius Brutus Booth, Jr., as Cassius, and John Wilkes Booth as Marc

Antony, had been mounted to subsidize a statute of Shakespeare in

Central Park, and resumed without further interruption. This was the

first and last time all three brothers had appeared on stage together.

It was only after the final curtain, when exiting theatergoers heard

newsboys barking headlines like “Rebel Plot: Attempt to Burn City,” that

the extent of the real life drama unfolding outside that Friday night

became clear. Confederate saboteurs had infiltrated New York City via

Canada, intending originally to disrupt the November 8 presidential

election. Thwarted by an infusion of federal troops, but still incensed

by the Union Army’s scorched earth campaign against Southern military

installations and industrial sites, they tried to set the city ablaze

instead,” starting fires “concurrently in about 19 hotels, a theater and

P. T. Barnum’s Museum. This touched off minor panics in a few places,

but mostly fizzled rather than sizzled. The plot to overwhelm the Fire

Department had the potential to be disastrous, however. “The plot was

excellently well conceived, and evidentially prepared with great care,”

The New York Times reported, “and had it been executed with one-half the

ability with which it was drawn up, no human power could have saved the

city from utter destruction.”

Harold Holzer, a Lincoln scholar and the author, most recently, of

“Lincoln and the Power of the Press,” said, “It’s hard to know whether

this . . . terrorist plot ever could have succeeded. The arson

technology involved was so primitive, and the would-be terrorists so

eager to flee from the fires they thought they would be setting . . .

that the enterprise was bound to fizzle rather than sizzle. But there is

no doubt that this was a deadly serious attempt to make New York howl in

the same way Sherman was, at that very time, making Georgia howl. It was

a plan to strike fear in the hearts of Northern civilians and break

their will to fight.

Eight saboteurs escaped to Canada, but one, Robert Cobb Kennedy of

Louisiana, was arrested when he slipped back into the United States en

route to Richmond. He was executed at Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor

. . . four months after the plot failed. He was the last Confederate

prisoner executed by the government before the Civil War ended two weeks

later.

Two mornings after their benefit performance raised $4,000 for the

Shakespeare statute (it still stands in the Mall in Central Park), the

Booth brothers met for breakfast at Edward’s home at 28 East 19th

Street. Like the performance, their breakfast was rudely interrupted.

Edward, who had just voted for the first time – for Lincoln – dismissed

John’s defense of the plot as just retribution for Union atrocities,

accused him of treasonous sentiments and demanded that he leave. Later,

in 1865, after his brother John killed Lincoln, Edwin Booth received a

letter from a friend in Washington revealing that an unidentified

21-year old whom Edwin had rescued a year earlier after he had slipped

off the platform at the Jersey City train station was none other than

Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s son. The letter was said to have

provided the Booth family some comfort.

[Editor’s note: The following story from The New York Times,

November 16, 2014, tracks to the last one.]

150 Years Later; Wrestling With a Revised View of Sherman’s March

By Alan Blinder

ATLANTA – This city would seem a peculiar place for sober

conversation about the conduct of William T. Sherman. To any number of

Southerners, the Civil War general remains a ransacking brute and bully

whose March to the Sea, which began here 150 years ago on Saturday, was

a heinous act of terror. Despite the passage of time; Sherman remains to

many a symbol of the North’s excesses during the Civil War, which

continues to rankle some people here.

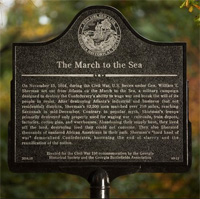

Yet this week Atlanta became the site of a historical marker

annotating Sherman folklore to reflect an expanding body of more

forgiving scholarship about the general's behavior. One of the marker's

sentences specifically targets some of the harsher imagery about him as

“popular myth.” W. Todd Groce, the president of the Georgia Historical

Society, which sponsored the marker, said of regional perceptions of

Sherman and the Union Army, “In general, we just have this image from

‘Gone With the Wind.’ ” Yet this week Atlanta became the site of a historical marker

annotating Sherman folklore to reflect an expanding body of more

forgiving scholarship about the general's behavior. One of the marker's

sentences specifically targets some of the harsher imagery about him as

“popular myth.” W. Todd Groce, the president of the Georgia Historical

Society, which sponsored the marker, said of regional perceptions of

Sherman and the Union Army, “In general, we just have this image from

‘Gone With the Wind.’ ”

The marker ... at the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum is

the fruit of a reassessment of Sherman and his tactics decades in the

making. Historians have increasingly written that Sherman's plan for the

systematic obliteration in late 1864 of the South's war machine,

including its transportation network and factories, was destructive but

not gratuitously destructive. Instead, those experts contend, the

strategy was an effective and legal application of the general's

authority and the hard-edged masterstroke necessary to break the

Confederacy.

They have described plenty of family accounts of cruelty as nothing

more than fables that unfairly mar Sherman's reputation. “What is really

happening is that over time, the views out there are being challenged by

historical research,” said John F. Marszalek, a Sherman biographer and

the executive director of the Mississippi-based Ulysses S. Grant

Association. “The facts are coming out.” To that end, the marker in

Atlanta mentions that 62,500 soldiers under Sherman's command devastated

“Atlanta's industrial and business (but not residential) districts” and

states that, “contrary to popular myth, Sherman's troops primarily

destroyed only property used for waging war – railroads, train depots,

factories, cotton gins and ware-houses.” Sherman's aggressiveness, the

marker concludes, “demoralized Confederates, hastening the end of

slavery and the reunification of the nation.”

The marker, placed in Atlanta at a time when more and more of its

residents are not natives of the area, drew relatively little criticism

ahead of its dedication ... Mr. Groce said. But some say its text

is an inaccurate portrayal of history that amounts to an academic pardon

for a general some believe committed acts that would now be deemed war

crimes... Jack Bridwell, a longtime leader of the Sons of Confederate

Veterans chapter in Georgia, was more blunt: “How they can justify

saying anything other than that he's ‘Billy the Torch,’ I don't know.”

The reassessment of Sherman comes at a time when the South continues

to weigh how to recognize its complex racial history. Earlier this year,

the National Center for Civil and Human Rights opened in Atlanta ...

But the Confederate battle emblem still flies on the grounds of the

South Carolina State House, and there is a push under way in Mississippi

to amend its Constitution to enshrine “Dixie” as the state song.

The new look at Sherman's legacy ... challenges deeply held opinions

of the general. “It has not been a legend white Southerners have been

particularly eager to surrender because it was all part of their sense

of grievance that they had been so severely wronged during the Civil

War,” said James C. Cobb, a professor at the University of Georgia and a

former president of the Southern Historical Association. “The old

stereotype is a long way from disappearing. There’s this sort of

instinctive sense of Sherman embodying the whole Yankee cause and the

presumed vindictiveness and unrelenting harshness that the white South

was subjected to.”

But Mr. Bridwell says such sweeping dismissals of Southern complaints

about the March to the Sea are meritless and, in the eyes of many,

repugnant. “There's still a strong resentment for what happened and how

it happened and for Sherman himself,” Dr. Cobb said. “They want to

whitewash everything and make it so much nicer than it was. It wasn't

nice. War isn't.”

There are few expectations here that Sherman will be the beneficiary

of an immediate and all encompassing wave of Southern good will. But Dr.

Cobb said he had sensed a shift in attitudes on his university campus in

Athens, east of Atlanta. “You all the time run into college kids who

don’t know which side Sherman was on -- and their parents and certainly

their grandparents would be aghast to know that,” he said... The

enduring nature of that lore, Mr. Marszalek said, was in itself a

testament to Sherman's maneuvers. “His whole concept was psychological

warfare," Mr. Marszalek said he did such a good job getting into

people’s minds, he's still there in many ways.”

Howie Krizer took the microphone to alert us to the "23rd Annual

Sarasota Civil War Symposium," January 21-24, 2015. For assistance, go

to cwea@earthlink.net or call (800) 298-1861. If you say, "I am a friend

of Howie’s," you will get a discount!

Last changed: 12/05/14

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|