Volume 26, No.

6 – June 2013 Volume 26, No.

6 – June 2013

Volume 26, No. 5

Editor: Stephen L. Seftenberg

Website:

www.CivilWarRoundTablePalmBeach.org

President's Message

It is with great sadness that I must report the

passing of Ed Lewis, one of the most supportive members of the

Roundtable. We all extend our sympathy to his widow, Bea.

Please remember that the Round Table will continue to

meet in the Mural Room at the Scottish Rite Hall in Lake Worth, 2000

North D Street, Lake Worth 33460, at 7:00 PM on the second Wednesday of

the month. The first two meetings at our new location went extremely

well. The management at the Scottish Hall has been very cordial and

helpful. The Round Table is fortunate to have such a great new centrally

located meeting place. We have several important requests:

1. We need volunteers on the "Reasonable

Grounds" committee to insure that the coffee is made before the

start of each meeting. Please contact me at a meeting to sign up.

2. The "Forage List" will be passed

around at all meetings. Every member is asked to bring in refreshments

once a year. Mary Ellen Prior will give you a reminder call a few days

before the meeting.

2. We all belong to the "Cleanup Committee"!

After a meeting, we are expected to return the room to the way we found

it. Please put any trash in the bins in the rear and return the tables

and chairs to their original positions. If we all do our part, cleanup

will be much quicker and easier.

3. Raffle tickets will be sold before the

meeting and drawn at intermission. Remember to bring in your

book donations. Books in good condition from any historical era will now

be accepted for the raffle. Many books are being donated to the

"CWRT Revolving Lottery" so they can be recycled after they have

been read. Bringing a popular book back leverages our Civil War Trust

fund.

4. We need a "Program Committee." We

have been extremely fortunate to have attracted many capable speakers,

both members and well-known authors and historians, but we have to keep

replenishing our scheduled speakers. This is a job that can be shared by

several interested members.

Gerridine LaRovere, President

June 12, 2013 Assembly

Guy Bachman will give a program entitled "Palm Beach County's

Influence on Training Civil War Leaders." Guy is a member of the Sons of

Union Veterans and the Loxahatchee Battlefield Preservationists and

anyone who has attended his battlefield lectures knows we can look

forward to a great talk..

May 8, 2013 Assembly

Janell Bloodworth, a member of the Roundtable since 1991, presented a

two-part program:

Part I: During the Civil War many women, usually Catholic nuns,

cared for the ill and wounded at great personal risk. Why did they do

it?

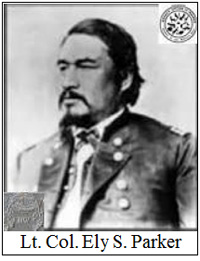

Part II: When the Articles of Surrender were copied to be

bound into pamphlets at Appomattox, the man entrusted with this task was

Ely Parker, a Seneca Indian. General Lee referred to him as a "real

American." What kind of man was Ely Parker?

It was the first of January, 1863. A new year was beginning but it

did not promise to be a happy one, since the country was in the middle

of a Civil War. Over Galveston, Texas, the air was thick with bullets. A

wounded Confederate soldier was lying on the ground. Suddenly he noticed

some women running through the hail of lead. He turned to a fallen

comrade and cried, "My God! Look at those women. What are they doing

down there? They’ll get killed!." His companion raised his head and

said, "Oh, those are the sisters. They’re looking for the wounded.

They’re not afraid of anything."

After the battle for Galveston ended, the nearby convent where the

Roman Catholic sisters lived was turned into a hospital. The two fallen

Confederate soldiers and 80 other Union and Confederate soldiers were

treated there. One of the wounded wrote home that the nurses treated

"all alike, whether they were Yankees or Rebels, black or white,

Catholic or non-Catholic. It didn’t make any difference to the sisters."

Seasoned Civil War veterans were not surprised to see nuns on the

battlefields. It was hard to miss women in unusual flowing robes and

strange headdresses! Green recruits found it hard to believe that these

women would tend to hordes of grotesquely injured soldiers, especially

with bullets passing overhead. And, they did it without any financial

reward.

The Catholic sisters were commonly called "Sisters of Mercy" or

"Sisters of Charity." They received their training in Catholic schools,

orphanages and hospitals. Their self-discipline and religious devotion

gave them the mental and emotional strength to cope with the horrors

they saw.

When the Civil War began, the military medical establishments were

woefully unprepared for the huge numbers of sick and wounded they would

have to deal with. There were not enough hospitals, not enough doctors

and not enough nurses. Although there were medical schools there were no

institutions for training nurses. The lack of military hospitals was

mind boggling. When the first thirty wounded were brought to Washington

there were no military hospitals there. Military hospitals that did

exist were located on or near forts around the country. The largest was

at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, and it could care for only 40 patients. At

the beginning of the war, military leaders on both sides took a very

unrealistic attitude about building new hospitals. They didn’t want the

bother or the expense. One quartermaster remarked, "Soldiers need guns

not beds." To be fair, most people, including those in the military,

thought the war would be over in three months, so there would be no need

for new hospitals.

Caring

for the injured and ill patients presented its own problems. The only

anesthetic in wide spread use was chloroform. Whiskey and morphine were

addictive. Ether had come into use in 1848 but was dangerous in

battlefield areas because it was highly flammable. Infection was

rampant. There was no understanding of germs or bacteria until 1865, the

last year of the war. As a result, there was no thought of sterilizing

dressings or the hands or gowns of the surgeons. Battlefield injuries

were not the main cause of death; two-thirds of deaths came from disease

– typhoid, malaria, cholera, pneumonia, dysentery, even measles. Caring

for the injured and ill patients presented its own problems. The only

anesthetic in wide spread use was chloroform. Whiskey and morphine were

addictive. Ether had come into use in 1848 but was dangerous in

battlefield areas because it was highly flammable. Infection was

rampant. There was no understanding of germs or bacteria until 1865, the

last year of the war. As a result, there was no thought of sterilizing

dressings or the hands or gowns of the surgeons. Battlefield injuries

were not the main cause of death; two-thirds of deaths came from disease

– typhoid, malaria, cholera, pneumonia, dysentery, even measles.

One of the few bright spots in this dismal situation was the

enlistment of hundreds of nuns for duty as military nurses. As the war

heated up, requests for the nun’s services came from both sides. During

the bloody Seven Days Campaign in Virginia in 1862, there was an extreme

need for nuns’ nursing abilities. The Confederate command actually

issued a desperate order: "Capture more Sisters of Mercy." Eventually

thousands of sisters volunteered for Civil War nursing duty. They worked

in military hospitals in large cities and in small towns, in both the

North and the South. Those working in the theaters of war might be

working for the Union one day and the Confederacy the next, depending

upon which army occupied the region at the time. Unlike most military

volunteers, the nuns chose to serve without pay. A dying soldier in a

hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio, was stunned to learn that the sisters who

were making his final days bearable were unpaid. "Not a cent?" he asked.

"No," a sister told him, "Catholic sisters work for the love of God and

not for the money." Not only were the sisters a bargain for both sides,

they also provided the very best medical care available at the time.

They were not amateurs. They had served long novitiates in asylums and

civilian hospitals.

The Daughters of Charity normally arrived at their posts with

complete staffs of expert executives, medical and surgical nurses,

trained dieticians, insanity experts and, sometimes, immunities to

certain contagious diseases. Early in the war a group of nuns worked as

nurses in a Union hospital in Point Lookout, Maryland. In the fall of

1863, the hospital was converted into a prisoner of war camp. The Union

command in Washington sent orders for the women nurses to leave. The

chief physician responded quickly, "We cannot dispense with the sisters’

services at this time." The sisters were allowed to stay.

The sisters’ refusal to show bias in treating patients was in

constant evidence. When a small Mississippi town temporarily changed

hands from Confederate to Union forces, a Union surgeon tried to stop

the sisters from caring for the Confederate patients. The sister

superior insisted that her nuns had the right to nurse "those poor men."

The surgeon objected, stating, "I am here representing the government."

The sister superior answered, "I am here representing something greater

than the government – humanity." She and her nuns continued to care for

all the patients. So scrupulously neutral were the sisters that they

were usually allowed to pass through the lines unchallenged by guards

and pickets. No countersigns were ever demanded. There is not one

recorded instance of a nun ever betraying the trust placed in her.

This trust and respect had not come about easily. They had deeply

rooted prejudices to overcome. The most obvious was that of women

working in a traditionally male field. The more insidious prejudices had

to do with ethnicity and religion. The Native American or "Know Nothing"

Party of the 1850s left an anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic sentiment in

its wake. Many of the sisters were Irish and German immigrants, in addition to being Catholic. Even Walt Whitman,

a poet and an army nurse, reflected this attitude, predicting that

Catholic nuns would not make good nurses among "home-born American young

men." Many prejudiced soldiers changed their minds after being in their

care. William Fletcher of the 5th Texas Infantry was shot in his left

foot during the Battle of Chickamauga. He refused to let the battlefield

surgeon amputate, Fletcher was evacuated to a hospital in Augusta,

Georgia. There most of the dressing of wounds was done by the Sisters of

Charity. Forty two years after the war ended, Fletcher wrote that he

"was raised with the belief that there was no place in Heaven for

Catholics, but my opinion changed. He reasoned, "If God consigned the

Sisters to hell, there was no use of my trying to avoid it. I had

already done enough to be on an unpardonable list." In 1897, Fletcher

helped plan and build a Catholic hospital in Galveston, Texas, in spite

of criticism form his non-Catholic neighbors.

and German immigrants, in addition to being Catholic. Even Walt Whitman,

a poet and an army nurse, reflected this attitude, predicting that

Catholic nuns would not make good nurses among "home-born American young

men." Many prejudiced soldiers changed their minds after being in their

care. William Fletcher of the 5th Texas Infantry was shot in his left

foot during the Battle of Chickamauga. He refused to let the battlefield

surgeon amputate, Fletcher was evacuated to a hospital in Augusta,

Georgia. There most of the dressing of wounds was done by the Sisters of

Charity. Forty two years after the war ended, Fletcher wrote that he

"was raised with the belief that there was no place in Heaven for

Catholics, but my opinion changed. He reasoned, "If God consigned the

Sisters to hell, there was no use of my trying to avoid it. I had

already done enough to be on an unpardonable list." In 1897, Fletcher

helped plan and build a Catholic hospital in Galveston, Texas, in spite

of criticism form his non-Catholic neighbors.

In an Atlanta hospital, a wounded soldier kept up a constant barrage

of verbal abuse on the sister who cared for him. She never ceased

responding to him kindly. Finally he was overcome by her patience and

kindness and begged for forgiveness. He explained, "When I came into

this hospital and found that the nurses were sisters, my heart was

filled with hatred and prejudice inherited from those nearest and

dearest to me. I did not believe that anything good could come from the

sisters, but now I see my mistake all too clearly."

After the war, many soldiers insisted that they survived only because

of the care the sisters provided. It was a known fact that death rates

in military hospitals dropped dramatically after sisters assumed nursing

duties. Many a time sisters saved the life of a man whom others had

given up as dead. It was not unusual for overworked surgeons to refuse

to treat men they felt had no hope of surviving. One soldier wrote, "Had

the sisters been here from the beginning, not a man would have died." In

1863, Sgt. Thomas Trahey of the 16th Michigan Infantry lay at the point

of death with typhoid when he contracted smallpox. The doctor gave up

hope for him but the sister in charge of his ward did not. Trahey spent

more than a year in hospitals in Frederick, Maryland and eventually

recovered. He later recorded that Sister Regina had dedicated herself to

curing him and had brought about his recovery.

Long after the guns fell silent, there would occasionally be happy

reunions between veterans and sisters. A young sailor, James Campbell,

on the USS gunboat Naiad, lay semi-comatose in a Memphis hospital for

weeks dying of malaria. The naval surgeons had given up on his case and

recommended that he be sent home to die. A young nun was not willing to

let him die. She stepped in and nursed him back to health. Twenty six

years later, Campbell, then Governor of Ohio, spoke to a crowd at Mount

Carmel Hospital in Columbus. At the reception, he met the Sister

Superior in charge of the hospital. In the course of their conversation,

Campbell realized that the Sister Superior was the young nun who had

fought for his life 26 years earlier.

Epidemics of smallpox and other contagious diseases often broke out

and it became necessary to quarantine the patients in "pest houses." Few doctors or male attendants

were willing to go near, so many pest houses were turned over entirely

to the nuns’ care. Many, if not most, of the sisters willing to work in

pest houses did not have the necessary immunities and some paid for

their dedication with their lives. The actual number of Catholic sisters

who died while caring for patients during the war remains unknown but it

is believed to be in the hundreds.

quarantine the patients in "pest houses." Few doctors or male attendants

were willing to go near, so many pest houses were turned over entirely

to the nuns’ care. Many, if not most, of the sisters willing to work in

pest houses did not have the necessary immunities and some paid for

their dedication with their lives. The actual number of Catholic sisters

who died while caring for patients during the war remains unknown but it

is believed to be in the hundreds.

Many nursing duties were performed away from the battlefield in

temporary or permanent hospitals. This does not mean the nuns were

always in secure facilities. Often they traveled in ambulances and

tended to the wounded and sick in army camps. Many sisters served on

river steamboats and other ships converted to military hospitals. The

chief surgeon on the Union hospital ship Superior asked Mother Felicitas

of the Sisters of Saint Francis to serve on his ship and bring along

"several very strong and especially capable sisters." When Gen.

McClellan left the Peninsula in 1862, the Daughters of Charity in Union

hospitals were directed to accompany their charges to be evacuated by

ship. One sister wrote, "When all the men, the sisters, the provisions

and the horses were on board, we seemed more likely to sink than sail!"

The bravery of the sisters in any circumstance could never be

questioned. In 1863 during the Siege of Vicksburg, the citizens of the

city hid in caves dug into the hills, but not the sisters. They were out

on the city streets tending to the sick and injured. There was, however,

one concession the sisters made to the danger: they obeyed the command

of their bishop not to "go out all together for I do not want you all to

be killed. Divide and work in different directions so that some of you

may escape." The sisters began working on the battlefields of Gettysburg

the day after the fighting ended and remained there for many months at

various hospitals. Two days after the battle, 16 sisters and a priest

left Emmitsburg, Maryland with bandages, clothing, sponges and

refreshments. On the battlefield the dead of both armies lay so thick

that wagon drivers had to be careful to avoid driving over bodies. In

the town of Gettysburg, building that could be found filled as fast as

the wounded could be carried in. So many needed attention that the

sisters had more nuns sent from Emmitsburg and Baltimore.

A most intriguing story to surface at Gettysburg was the love story

of Kate Hewitt and Major John Reynolds, who had planned to be married.

His family received two other shocks along with the news of his death:

The first was that the 42-year old bachelor was engaged to be married

and the second was that both he and Kate had recently converted to

Catholicism. Eight days after John’s funeral, Kate entered the convent

of the Daughters of Charily in Emmitsburg, becoming Sister Hildegardis.

Kate had promised John that if he were killed she would marry no other

man. She kept her promise and lived the rest of her life as a nun.

After the war, Jefferson Davis was moved to commend the sisters

publicly: "I can never forget your kindness to the sick and wounded in

our darkest days. I do not know how to testify my gratitude and respect

for every member of your noble order."

As the years passed, less and less was heard of the contributions of

the sisters. The chief reason was probably that the sisters discouraged

self-promotion. They rarely recorded their countless contributions. "The

sisters did much and wrote little." Union soldier Jack Crawford wrote,

"My friends, on God’s green and beautiful earth there are no more

kindhearted and self-sacrificing women than those who wear the somber

garb of the Catholic sisters. I am not Catholic but I stand ready at any

time to defend those noble women with my life, for I owe that life to

them."

After well-earned applause and a pause for refreshments, Janell

turned to the story of Ely Parker (1828-95) who was Indian birth name

was Hasanoanda and his adult name was Donehogawa.

On the morning of April 9, 1865, Ulysses S. Grant was suffering with

a horrendously painful migraine headache. A Confederate soldier arrived and informed him that

Robert E. Lee was ready to give up the fight, ready to end the Civil War

after four long and bloody years that had destroyed over 600,000 lives

and major portions of many Southern cities and towns. When Grant

realized that the surrender of Lee’s army was at hand, his headache

immediately disappeared. That afternoon, Lee and Grant met in the parlor

of the McLean house in the hamlet of Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

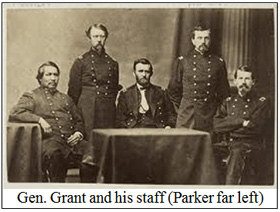

After exchanging small talk, Grant insisted on introducing his staff

members to Lee individually. Lee, ever courteous, shook each man’s hand.

When he came to Lt. Col. Ely Samuel Parker, Lee extended his hand with

the gracious comment, "I am glad to see one real American here." Parker

accepted the handshake and responded, "We are all American."

migraine headache. A Confederate soldier arrived and informed him that

Robert E. Lee was ready to give up the fight, ready to end the Civil War

after four long and bloody years that had destroyed over 600,000 lives

and major portions of many Southern cities and towns. When Grant

realized that the surrender of Lee’s army was at hand, his headache

immediately disappeared. That afternoon, Lee and Grant met in the parlor

of the McLean house in the hamlet of Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

After exchanging small talk, Grant insisted on introducing his staff

members to Lee individually. Lee, ever courteous, shook each man’s hand.

When he came to Lt. Col. Ely Samuel Parker, Lee extended his hand with

the gracious comment, "I am glad to see one real American here." Parker

accepted the handshake and responded, "We are all American."

Among his other duties, the 37-year old Parker served as one of

Grant’s military secretaries. Once the generals had agreed on surrender

conditions, Parker was directed to copy the articles of surrender into a

bound pamphlet in which multiple copies would be produced through the

use of carbon paper inserts. This done, Parker passed the book to

another aide who was to prepare the final copy in ink for signature.

Unnerved by the magnitude of the occasion, the aide was forced to leave

the task to the unflappable Parker, who quickly produced the copy in his

graceful hand. Lee examined the document briefly, then had an aide draft

a letter for his signature accepting the terms. Grant accepted this

letter unopened and the surrender was complete. Parker casually put a

copy of Grant’s original draft in his jacket pocket. Later, after Grant

became President, he put his signature on the draft, attesting to its

authenticity. This document became a favorite heirloom of the Parker

family.

Parker may be best known for his role in Lee’s surrender, but his

life work was far greater than that single act. This "one real

American," as Lee referred to him, was born destined to greatness, or so

it had been prophesied. Four months before his birth in the Tonawanda

Seneca Reservation in Indian Fall, New York, Parker’s mother had an

unsettling dream. She visited a Seneca dream interpreter. Among other

things, he told her, "A son will be born to you who will be a

peacemaker. He will become a white man as well as an Indian. He will be

a wise white man, but never desert his Indian people." As it happened,

the prophecy became true!

Parker was educated at Elder Stone’s Baptist school, but he did not

do well, even failing to learn English. So he was packed off to an

Iroquois settlement in Ontario to learn woodcraft. After three years

there he became homesick and walked home. He was then 13 years old. An

incident occurred on the way that changed his life: he was ridiculed by

British officers for his poor grasp of English. This hardened his

resolve to learn the language. He returned to the Baptist school where

his intelligence and perseverance won him tuition-free admission to

Yates Academy, a noted school in Orleans County, New York. He was so

outstanding that his tribal elders sent him, at age 15, to Washington to

represent his reservation regarding several treaty disputes. Parker so

impressed Washington society that when he was 18 he was invited to dine

with President and Mrs. Polk in the White House.

Continuing his education, Parker matriculated in the prestigious

Cayuga Academy in Aurora, Ontario. There, his involvement in the debate

club stimulated his interest in the law. He read law for the customary

three years in Ellicottville, New York but then was denied the right to

take the bar examination because, as a Seneca, he was not considered a

United States citizen at that time. It was not until 1924 that all

American Indians were considered citizens under the Indian Citizenship

Act of 1924. Thwarted in his attempt to practice law, he elected to

become an engineer, working on various projects, including improvements

to the Erie Canal. Due to his accomplishments and pleasing personality,

Parker was welcome in society throughout his life. In 1847 he became a

Mason and remained one until he died. In 1851, the Iroquois in

recognition of his service, bestowed on Parker their greatest honor,

naming him Grand Sachem of the Six Nations. He became a mentor and an

intermediary for his people. The Governor of New York recognized him as

the chief representative of the Iroquois Confederacy. His success in

negotiating with New York and the United States enabled the Tonawanda

Seneca to save three-fifths of their reservation.

Parker’s star continued to rise in the white man’s world. He became a

captain of engineers in the 54th Regiment New York militia. In 1857, he

was appointed superintendent of lighthouse construction on the upper

Great Lakes. Among his various postings, he spent some time in Galena,

Illinois. There, in 1860, he struck up a life-long friendship with a

down-and-out former Army officer and harness store clerk, one Hiram

Ulysses Grant, the man who, due to a clerical error at West Point would

become known as Ulysses S. Grant.

When the Civil War began, Parker tried to join the U. S. Army. In

mid-1861 he went to Albany and volunteered to raise a regiment of

Iroquois to fight for the Union. He was flatly refused, the Governor

making it clear that Indians were not welcome as volunteers. Then he

offered his services as an engineer, only to be rebuffed again.

Secretary of State William Seward put it to him bluntly, "The fight must

be settled by white men alone. Go home, cultivate your farm and we will

settle our troubles without any Indian aid." Dispirited, Parker went

home and tended his crops for two years, busying himself with Masonic

and Seneca activities.

In 1863, Gen. Grant needed engineers and granted Parker his wish,

brevetting him as a Captain of Engineers in the U. S. Army. But now a problem cropped up: according to

Iroquois custom, no Grand Sachem could go to war and retain his tribal

titles. Fortunately, a special dispensation was made because this was

not a war against another tribe but a war "between white men." Parker

worked his way up the military ladder and by 1864 he became a member of

Grant’s personal staff and his de facto personal military

secretary. Much was made of "Grant’s Indian" as Parker came to be

called. He was a physically imposing man -- though just 5 feet 8 inches,

he weighed 200 pounds. He was extraordinarily intelligent: "200 pounds

of encyclopedia" one of his army friends called him. Being soft-spoken

and polite, he made a positive contribution to Grant’s inner circle.

During the war he also became friends with President Lincoln and Matthew

Brady, the famous photographer. After the war, Parker stayed on as a

member of Grant’s staff until 1869. He spent much time as an emissary to

Indian tribes in the West. He was popular among Indians who were

gratified that the Washington politicians would send another Indian to

treat with them.

Engineers in the U. S. Army. But now a problem cropped up: according to

Iroquois custom, no Grand Sachem could go to war and retain his tribal

titles. Fortunately, a special dispensation was made because this was

not a war against another tribe but a war "between white men." Parker

worked his way up the military ladder and by 1864 he became a member of

Grant’s personal staff and his de facto personal military

secretary. Much was made of "Grant’s Indian" as Parker came to be

called. He was a physically imposing man -- though just 5 feet 8 inches,

he weighed 200 pounds. He was extraordinarily intelligent: "200 pounds

of encyclopedia" one of his army friends called him. Being soft-spoken

and polite, he made a positive contribution to Grant’s inner circle.

During the war he also became friends with President Lincoln and Matthew

Brady, the famous photographer. After the war, Parker stayed on as a

member of Grant’s staff until 1869. He spent much time as an emissary to

Indian tribes in the West. He was popular among Indians who were

gratified that the Washington politicians would send another Indian to

treat with them.

In 1867, Parker finally married --but not to an Indian. His bride was

a Washington socialite, Minnie Orton Sackett, the daughter of an officer

killed in the war. They were married on Christmas Eve. Grant stood as

his best man and gave the bride away in the absence of her father. As

you can imagine, the marriage caused something of a stir in Washington

society. The couple were maltreated on more than one occasion by their

not-so-enlightened contemporaries.

When Grant became President, he appointed Parker as Commissioner of

Indian Affairs and head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He was the

first Indian to hold the office. His two-year reign was a tempestuous

one. He was too honest, too interested in the cause of justice for his

own race, for it to be otherwise. Parker’s first act was to sweep the

Bureau clean of its entrenched bureaucrats, who often sold supplies to

the Indians at inflated prices and pocketed the profits. This was the

established way of doing business in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. To be

fair, not all the agents were guilty, but enough were to tarnish the

Bureau’s reputation. Parker set out to change all that, replacing the

old civilian agents with reputable Army personnel and Quakers, whom he

believed would be less corruptible. He may have been naive, he did quell

a lot of the wheeling and dealing at the Indians’ expense. Of course, as

the saying goes, "No good deed goes unpunished." Parker’s reforms earned

him powerful enemies. In the summer of 1870, Parker toured the American

West and personally examined the Indian situation. He soon observed that

severe food shortages along the Missouri River were leading to short

tempers on the reservations. In order to avoid trouble, the Indians must

be fed and fed quickly. As the Governor of the Dakota Territory told

Parker, "We must either feed or fight the Indians." Unfortunately,

Parker’s enemies in Congress conspired to delay appropriations needed to

purchase food and supplies. Parker had to go outside proper channels to

acquire the urgently needed food for the desperately hungry Indians. Had

he not done so, the Indians would have attempted to break out of the

reservations and fend for themselves.

A political enemy, William Welsh, a member of the Board of Indian

Commissioners, accused Parker of fraud and of being unqualified to head

the Bureau. Parker was called before a committee of the House of

Representatives and after a lengthy hearing, he was exonerated of any

wrongdoing and even complimented for averting a major Indian war that

could have cost the US Treasury millions of dollars and many lives to

extinguish. Unfortunately, Congress passed a law that required Parker to

consult the Board on all matters, relegating him to a "figurehead." This

was too much for a proud Seneca to bear. After several months of soul

searching, Parker resigned. Despite his unfortunate downfall, his

accomplishments at the Bureau of Indian Affairs were significant. He

organized a "peace policy" with the Indians and he managed to root out

(at least temporarily) much of the rot within the system. The simple

fact of his being an Indian impressed the tribes under his care and put

them at their ease. Finally, he put an end to the treaty making policies

of previous administrations that had always been strictly to the white

man’s advantage. Although some violence did take place, he could boast

that there had been no Indian wars during his two-year tenure.

After his government service, Parker worked on Wall Street and later

in the New York City Police Department. He managed to stay active in the

militia, various military societies and the Masons, achieving high rank

within each organization. He and his wife became well respected in New

York social circles. Their only child, a daughter, was proud of her

Indian heritage. Her father fondly referred to her as "Beautiful

Flower." Eventually she married a member of one of Massachusetts’ most

prominent families.

Ely Samuel Parker died in 1895, after having been plagued with

strokes and diabetes. Although some of his contemporaries were, at

times, less than fair to him, history has treated Commissioner Parker

most kindly. Had Robert E. Lee been alive at the time of Parker’s death,

he probably would have remembered what he said when he first met Parker

30 years earlier: "I am glad to see one real American here."

Janell received a well-earned round of applause and much questioning

about her wonderful topics.

[Editor’s note: Two interesting quotes: (1) "When James P. Kelly, the

sculptor, had General Parker posing for his bust, he remarked, "... you

are the most distinguished Indian who ever lived." "That is not so," was

the laconic reply."Ah, General," said Mr. Kelly," I see you have not

caught my meaning... I mean that you... have torn yourself from one

environment and made yourself the master of another. In this you have

done more for your people than any other Indian who ever lived..." (2)

After first being buried near his Connecticut home, Parker was later

interred in ancestral Seneca lands, thus fulfilling the prophecies that

accompanied his mother’s dream – "the ancient land of his ancestors

will fold him in death."]

Last changed: 06/07/13

Home

About News

Newsletters

Calendar

Memories

Links Join

|