|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Volume 25, No. 7 – July 2012

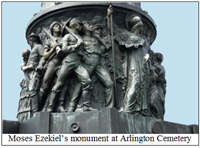

Volume 25, No. 7 President’s Message The Civil War Round Table of Palm Beach County needs your help! We need a Speaker’s Committee and we need speakers. The talks can to be long on any subject or they can be short biographies of men and women who were involved individually and in groups before, during and after the Civil War as soldiers, politicians, volunteers, etc. I am temporarily asking volunteer speakers to call Steve Seftenberg, our already hard working editor, with topics. Be creative! Be educational! Be controversial! Have fun!! Once a year we ask each member to bring a refreshments to one meeting. Please add your name when the sign-up sheet passed around at the next meeting. Mary Ellen Prior will call a few days before the meeting to remind you when it is your turn. Just like the troops, our Round Table travels on its tummy. Gerridine LaRovere, President Wednesday, July 11, 2012 Program Monroe Ackerman, a master spellbinder, will talk on "Civil War Diplomacy." Wednesday, June 13, 2012 Program Marsha Sonnenblick, one of our most popular speakers, attracted a mid-summer crowd of 50 attendees to hear her talk, "Jews in the Civil War." In 1850, the Jewish population in the United States did not exceed 50,000. Driven by persecution following the mid-century revolutions, the Jewish population in the United States in 1860 had tripled to over 150,000, of whom 120,000 lived in Northern cities and 30,000 lived in the South. The immigrants came primarily from Prussia, Bavaria, Moravia and Bohemia. The American response to the Jewish presence was complex. Legal restrictions against Jews holding office and voting were maintained in a few states. The "No Nothing" Party pandered to wide spread anti-nonnative sentiment. Yet in general the civil and economic rights enjoyed by Jews compared favorably to the state-sponsored discrimination and organized violence experienced in Europe. Some Jews became successful economically and politically. In the South, Jews were viewed as "white" and some even owned slaves. When war came, why and how did Jews pick sides? Contrary to "conventional wisdom" that Civil War soldiers, like their more modern counterparts, had little or no idea of what they were fighting for, James H. McPherson, in What They Fought For (1861-65), based on reading 25,000 letters and hundreds of diaries, asserts that ideology played a far more important role than previously believed. Ms Sonnenblick finds support for this in a series of quotes. First, from the South: Rabbi Poznasanski, rededicating a Charleston, South Carolina, synagogue, predicted that if Secession came, Jews in Charleston would fight for the South. He said: "This synagogue is our temple, this city our Jerusalem, this happy land our Palestine, and as our fathers defended with their lives that temple, that city and that land, so will their sons defend this temple, this city, this land." Rabbi Morris Raphel, of New York’s Beth Jeshuren, an Orthodox Fundamentalist, and the first Jewish rabbi to deliver the daily prayer in the U. S. Senate in 1860, delivered the following in a sermon in 1860: "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house, or his field or his . . . slave. The Ten Commandments are the word of G-D, and as such, of the very highest authority, is acknowledged by Christians as well as by Jews. I would therefore ask the Reverend William Lloyd Garrison and his compeers how dare you denounce slaveholding as a sin. Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Job, . . . all these men were slaveholders." (Ms. Sonnenblick commented that Rabbi Raphel overlooked the injunction to the Israelites in Exodus 2l:2 to free their slaves after 7 years.) Later on, as Gen. Grant threatened Richmond, Rabbi Michenbaum prayed, "Grant us freedom from these tyrants!" Ms Sonnenblick commented, dryly, God gave them Grant instead! Many Jews in the North were ambivalent about slavery because abolitionists such as Garrison were also violently anti-Semitic. Many Jews also feared emancipation would allow blacks to take their jobs. Some Northern Jews were strongly pro-Union, whether or not they were for emancipation. For example, the Washingtoner Intelligenzblatt, on July 7, 1860, printed an editorial stating: "We immigrant citizens have the holy duty to throw ourselves into the breach and to preserve the Union and the Constitution, these great legacies of the Revolution, for the future. The native Americans are demoralized physically and spiritually. Love, true attachment for this is entirely lacking. They do not understand free institutions because to them the difference between freedom and despotism is unknown. To us immigrants it is reserved to save this land from destruction. And we will do it!" Rabbi David Einhorn, the Baltimore Reformer, staunchly upheld his Abolitionism in the slaveholding State of Maryland, notwithstanding the opposition of his congregation and threats to his personal safety. He fled to New York from a mob in 1861. There were also Rabbis who carried their Abolitionist convictions into action: two such fought with John Brown in Kansas. One Rabbi served in combat in the Union Army.

Her next subject was Judah Philip Benjamin (August 6, 1811

Ms Sonnenblick then introduced us to the extended Moses family: Samuel P. Moses became the first Jewish Surgeon General in the Confederate Army; his son, Albert Moses Luria killed at the age of 19 on May 31, 1862, was the first Jewish Confederate casualty and Albert’s cousin, Andrew Jackson Moses, killed on April 9, 1865, defending Mobile, Alabama, was the last.

Next came two Confederate women who served in diametrically different ways: Eugenia Levy Phillips Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Charleston, SC, in 1819 or 1820 [sources differ], Eugenia Levy Phillips was raised by prominent and successful parents who mingled easily with Charleston's elite. She married Philip Phillips and moved to Washington, D. C., when Phillips was elected to Congress in 1853-55, after which he went into private legal practice. Although a native Southerner, he remained opposed to Southern secession. His wife, like many Southern Jews, was a strong supporter of the Confederate cause. She collaborated directly with the Confederate military. Beginning in 1861, she aided Confederate spy networks and secretly passed material aid to Confederate troops. On August 24, 1861, Union troops raided the Phillips home; although they were unable to find direct evidence of treason, they placed Phillips under house arrest. At the intervention of Edwin Stanton, who later became Secretary of War, she was soon released and the family moved to New Orleans. The Union army won control of New Orleans in early 1862, and Phillips was arrested in May after laughing during a funeral procession for a Union soldier. She was imprisoned with other Confederates on Ship Island, Mississippi. She was released several months later and the family moved to Georgia.

Ms Sonnenblick then explored the "Chaplain Controversy." At the outbreak of the war, there was no provision for chaplains in the U.S. armed forces. In July 1861, Congress adopted a bill permitting each regiment's commander to appoint a regimental chaplain but only if he were "a regularly ordained minister of some Christian denomination." Only Rep. Clement L. Vallandigham of Ohio, a non-Jew (and later the vilified leader of the Copperheads, who wanted "to maintain the Constitution as it is, and to restore the Union as it was.") thought the law endorsed Christianity as the official religion of the United States military and was blatantly unconstitutional, but the law passed easily. Shortly thereafter, the YMCA filed a formal complaint against Michael Allen, who was serving as chaplain to a Pennsylvania regiment but was neither a Christian nor an ordained minister. The Army forced Allen to resign his post. Hoping to create a test case based strictly on a chaplain's religion and not his lack of ordination, Colonel Max Friedman and the officers of the same regiment then elected an ordained rabbi, the Reverend Arnold Fischel (1830-1894), to serve as regimental chaplain-designate. When Fischel, a Dutch immigrant, applied for certification as chaplain, the Secretary of War, rejected Fischel's application. This act stirred American Jewry to action. The American Jewish press let its readership know that Congress had limited the chaplaincy to those who were Christians and argued for equal treatment for Judaism before the law. A handful of Christian organizations, including the YMCA, reacted by lobbying Congress against the appointment of Jewish chaplains. To counter their efforts, the Board of Delegates of American Israelites, one of the earliest Jewish communal defense agencies, recruited Reverend Fischel to move to Washington and lobby President Lincoln to reverse the chaplaincy law. Armed with letters of introduction from Jewish and non-Jewish political leaders, Fischel met with President Lincoln. Fischel explained to Lincoln that he came not to seek political office, but to "contend for the principle of religious liberty, for the constitutional rights of the Jewish community, and for the welfare of the Jewish volunteers." According to Fischel, Lincoln asked questions, "fully admitted the justice of my remarks" and promised he would submit a new law to Congress "broad enough to cover what is desired by you in behalf of the Israelites." On July 17, 1862, Congress passed and Lincoln's signed a law allowing "the appointment of brigade chaplains of the Catholic, Protestant and Jewish religions." In its first lobbying effort, American Jewry had won the first major victory in favor of the separation of church and state. In today’s military even Wiccans are permitted to have their religious leaders. Marsha then turned to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s infamous "Order No. 11," issued December 9, 1862, which stands out in American history as the first instance of a policy of official anti-Semitism on a large scale. Underlying the order was a negative image of Jewish merchants and the belief that Jews were part of a black market in Southern cotton. Although at war, the North and South still relied on each other economically. The North especially needed Southern cotton for the production of military tents and uniforms. The Union army would have banned trade with the South completely but President Abraham Lincoln preferred limited regulated trade in cotton. The Battle of Shiloh made trade in cotton and other goods possible by opening up the Mississippi River down to Vicksburg. This soon became very profitable for both sides; army officers, treasury agents, and individual speculators became involved, although Jews were distinctly a minority. By the fall of 1862, trading was getting out of hand. Grant was annoyed that requests for trading licenses distracted him from planning the capture of Vicksburg. When Grant's own father sought licenses for a group of Cincinnati merchants, among whom were some Jews, the general issued his order. Although some of the traders were Jewish, most were not. Among the higher ranks of the Union Army the words "Jew," "profiteer," "speculator" and "trader" all meant the same thing , while the Union commanding General Henry W. Halleck lumped together "traitors and Jew peddlers." Grant concurred, describing "the Israelites" as an "intolerable nuisance." The Jews were made scapegoats because of old European prejudices and anti-Semitism. Order No. 11 besmirched Grant’s record for years: "The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled from the department [the "Department of the Tennessee," an administrative district of the Union Army of occupation composed of Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi] within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order. Post commanders will see to it that all of this class of people be furnished passes and required to leave, and any one returning after such notification will be arrested and held in confinement until an opportunity occurs of sending them out as prisoners, unless furnished with permit from headquarters. No passes will be given these people to visit headquarters for the purpose of making personal application of trade permits." The order implied that all Jews in the region were speculators and traders, which they were not. Despite this, Grant's subordinates carried out the order with a vengeance. In Holly Springs, the Jewish traders in the area had to walk 40 miles to evacuate the area. Thirty Jewish families, long time residents of the town, also had to leave though none of them engaged in cotton speculation and two of them had served in the Union Army. The order caused an uproar and was criticized by some Jews, as well as non-Jews in opposition to Lincoln and his party as an example of their willingness to trample on civil liberties. Peace Democrats complained that the Republicans were more concerned with the rights of blacks than of Jews, who were white. Jewish leaders organized protest rallies in St. Louis, Louisville and Cincinnati, while the leaders of the Jewish communities in Chicago, New York and Philadelphia sent telegrams to Lincoln protesting the order. Cesar Kaskel, a Paducah, Kentucky, merchant, sent a telegram to Lincoln condemning Grant's actions and led a delegation to Washington, arriving in Washington two days after the Emancipation Proclamation became law. Kaskel and his group met with the influential Jewish Republican, Adolphus Solomons, and was accompanied to the White House by Cincinnati Congressman John A. Gurley. They showed Lincoln documents proving that the Jews who had been expelled from their homes were upstanding citizens not involved in cotton speculation. Lincoln ordered General Halleck, General in Chief of the Army, to revoke the order immediately. Grant never defended himself, even though his order was used to vilify him in the 1868 election. His term as President was the best for Jews since George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. No President did more for Jews until the 20th Century. In 1869, he offered to appoint Joseph Seligman (1820-1880), one of the foremost bankers of the day, as the first Jewish Secretary of Treasury. Seligman declined. Grant successfully fought a proposed law that would have made Christianity the official religion of the United States. Jacob da Silva Solis Cohen was a Sephardic Jew who served with both the Union Army and Navy, most notably as an assistant surgeon with Dupont’s expedition to Port Royal and with the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. He made himself an expert on diseases of the throat. After the war he returned to a distinguished medical and civic career in Philadelphia. The Medal of Honor was created during the Civil War and is the highest military decoration presented to a member of our armed forces. The medal is bestowed "for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life, above and beyond the call of duty, in actual combat against an armed enemy force." Six or Seven Jews (the status of one of the following is in doubt) were awarded this medal in the Civil War (in alphabetical order): Abraham Cohn, Army Sergeant Major -- During Battle of the Wilderness (May 4, 1864) "he rallied and formed, under heavy fire, disorganized and fleeing troops of different regiments." At the Battle of the Crater, Petersburg (July 30, 1864), "he bravely and coolly carried orders to the advanced line under severe fire." Isaac Gause, Army corporal -- Near Berryville, Virginia, September 13, 1864, he "captured the colors of the 8th South Carolina Infantry while engaged in a reconnaissance." Abraham Greenawalt, Army private -- In the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, November 30, 1864, he "captured corps headquarters flag (C.S.A.)." Henry Heller, Army sergeant -- In the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, May 2, 1863, he was "one of a party of 4 who, under heavy fire, voluntarily brought into the Union lines a wounded Confederate officer from whom was obtained valuable information concerning the position of the enemy." Leopold Karpeles, Army sergeant--In the Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia, May 6, 1864, "While color bearer, he rallied the retreating troops and induced them to check the enemy's advance."

David Orbansky, Army private -- Shiloh, Tennessee, Vicksburg, Mississippi,1862 and 1863, "Gallantry in actions" The highest rank a Jew was permitted to attain in the Confederate Army was major. In contrast, the Union Army had five Jewish generals and the Union Navy had one Jewish surgeon general:

Leopold Blumenberg was a lieutenant in the Prussian Army in 1848, who immigrated to the United States in 1854. An avowed abolitionist, he narrowly escaped lynching by a secessionist mob in Baltimore in early April 1861. With the start of the war, Blumenberg helped organize the Maryland Volunteer Regiment and fought with it in the Peninsular campaign. He was severely wounded in the Battle of Antietam in 1862, and subsequently was appointed a brevet brigadier general. A brevet military appointment is a commission usually granted as an honor, carrying the rank of the new office but without an increase in pay or authority. One Jewish officer who only made it to general's rank posthumously was Lieutenant Colonel Leopold Newman of New York. He distinguished himself at the First Battle of Bull Run. Newman was subsequently severely wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863, and he died in a Washington hospital before President Abraham Lincoln could present him with a commission to brigadier general. Perhaps the most notable of the Jewish generals was Edward S. Salomon of Illinois. Salomon emigrated from Germany to Chicago in 1854. He was elected to the Chicago City Council at the age of 24, the youngest member of that body. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Salomon enlisted in the 25th Illinois Infantry as a second lieutenant and won quick promotions for battlefield bravery. At Gettysburg in 1863, he was colonel in command of the 82nd Illinois Volunteer Infantry, which had over 100 Jewish personnel. His unit fought at Cemetery Ridge and was one of the principal Union forces that successfully repulsed Pickett's charge. Salomon received a commendation for bravery and was brevetted a brigadier general. Salomon served with General Sherman in the Battle for Atlanta and was cited as "one of the most deserving officers." After the war he led his men in a six-hour victory parade in Washington D.C., a commanding general at the age of 29. Brigadier General Alfred Mordechai graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and received high commendations for his conduct at the Battle of Bull Run. He became the chief ordnance officer in several Union regiments and, in 1865, was appointed instructor of ordnance at West Point. Among the other Jewish generals in the Union forces were Phineas Horowitz of Baltimore, who was appointed surgeon general of the Navy during the war, and General William Meyer of New York, who received a letter of thanks from President Lincoln for his efforts during the New York draft riots.

In the field near Big Black, MS 6/7/63 My dear wife! It is nearly one year since I was called upon to witness the fourth birth of our beloved and blooming offspring. Well do I remember sufferings: as if it were but a moment ago, do I remember the heroic and womanly like demeanor and the loving and confiding looks I received from you, during all your labor and the joy we both felt when the lovely and pretty Hattie was presented by my dear mother, who at once pronounced her "the prettiest child she has ever seen." "Allow me to congratulate you on her first "birthday." May god our heavenly Father grant that we may live to see many, many of them in peace, love and happiness. May it please God to give us many happy days with our Children, so that we may raise them an ornament to Him and an emulation to His teachings. "I would love to be with you tonight: I know and feel you are just now thinking of me, but we still have to wait a while, trusting that Vicksburg will soon fall. "With hearty prayers for y our welfare and that of our beloved Children, I remain to the best and loveliest wife in the world, a true and loving husband, Marcus. "P. S. You don’t know how much I love you." The 82nd Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry was one of the three "German" regiments furnished to the Union by Illinois. Approximately two-thirds of its members were German immigrants and most of the other third was composed of immigrants from various countries. Company C was entirely Jewish, and Company I all Scandinavians. Its first commander was Col. Friedrich Hecker. It lost 155 men (23 casualties and 89 prisoners) at Chancellorsville, including Colonel Hecker, who was badly wounded. In the fall of 1863, it moved to the Western Theater. Colonel Hecker had recovered from his wounds by now and was promoted to brigade command. Hecker was succeeded as commander of the 82nd Regiment by Edward S. Salomon (whose career Marsha has already discussed) After seeing action at Chattanooga, the 82nd Illinois joined the rest of Sherman's army in the 1864-65 campaigns in Georgia and the Carolinas. Distressingly, there was a resurgence of anti-Semitism in the 1890s. In 1896, a group of Jewish Civil War veterans organized the Hebrew Union Veterans, to dispel the belief that Jews didn't fight in the Civil War. This group evolved into the Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America.

In November 1853, a sixteen-year-old Twain wrote from Philadelphia that the Jewish presence had "desecrated" two historic homes there. And in a newspaper article of 10 April 1857 he asserted that "the blasted Jews got to adulterating the fuel." Although he later indicated that his experience taught him that Jews were not the evil characters he had been taught as a child, in 1879 he observed that "the Jews are the only race who work wholly with their brains and never with their hands... They are peculiarly and conspicuously the world's intellectual aristocracy. " In other words, he still stereotyped Jews, ignoring the realities of impoverished Jews and exploited Jewish labor in American cities. In his famous essay, "Concerning the Jews," written in 1898 and first published in Harper's Monthly in September 1899, Twain claimed to be free of anti-Semitism and to be writing in defense of Jews. Although he praised the Jews for their charity, close family life, hard work, and "genius," he repeated the slander that the Jews were frequent and capable officers in the civil service, but had an "unpatriotic disinclination to stand by the flag as a soldier." This was ironic because Twain may or may not have served several weeks with the Confederate Army and then deserted! In contrast, up to 10,000 Jews may have fought in the Civil War -- a much higher proportion than their percentage of the general population. Twain’s solution was for regiments of Jews and Jews only to enlist in the army so as to prove false the charge that "you feed on a country but don't like to fight for it." In reaction to angry letters from American Jews who read the essay, Twain retracted this statement in a postscript and noted that despite having to endure American anti-Semitism, Jews fought widely and bravely in America's wars. Therefore, "that slur upon the Jew cannot hold up its head in presence of the figures of the War Department." Marsha finished her wonderful talk by mentioning Irene goldsmith Cohen, the President of the South Carolina Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, as an example both of the fact that Jews took both sides in the Civil War and that the Civil War has a remarkable call on our memories.

Last changed: 06/27/12 |